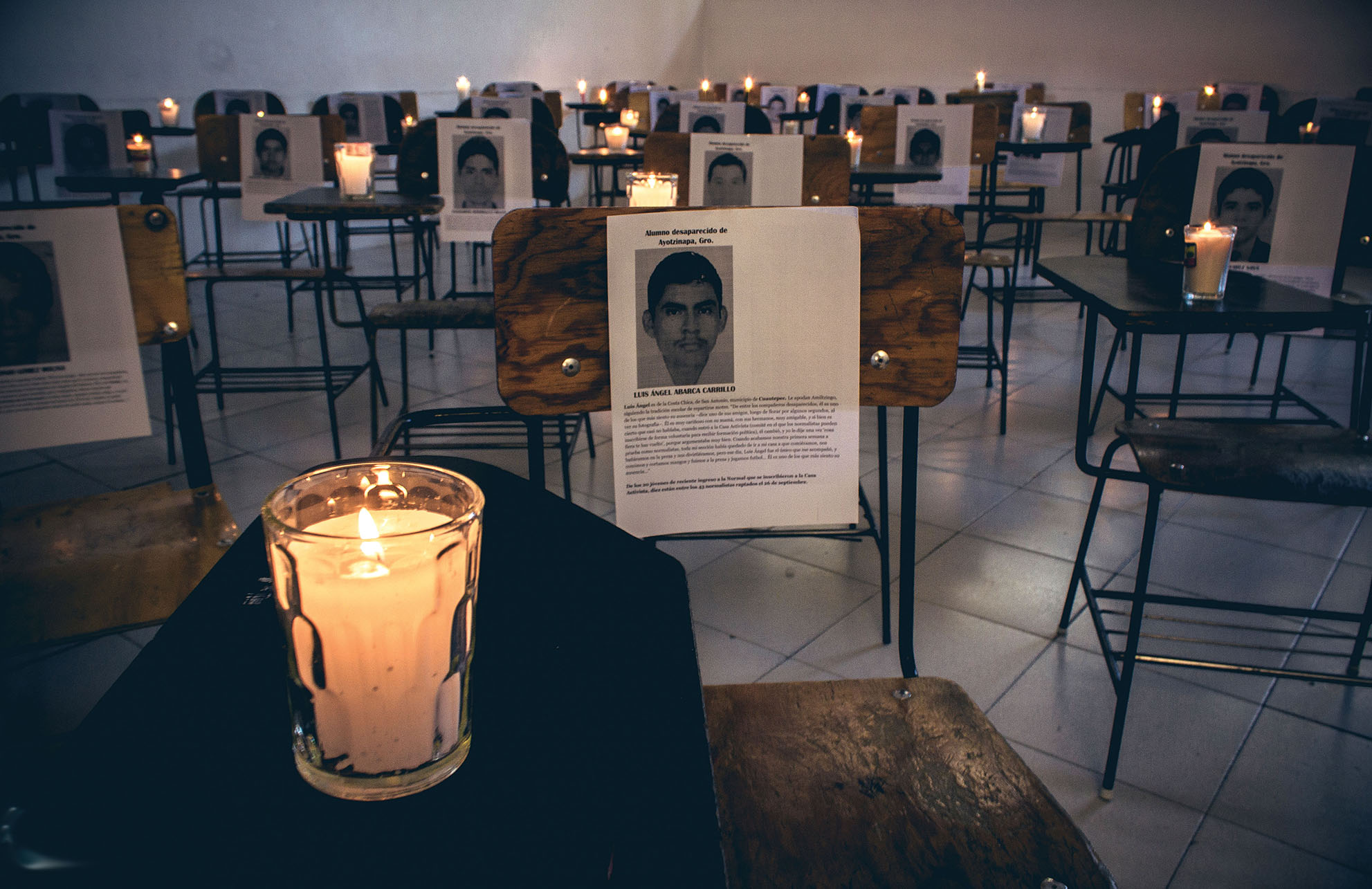

On September 26, 2014, more than 100 students from a rural teachers training college in Ayotzinapa, Guerrero, Mexico, boarded a caravan of buses headed toward the town of Iguala to protest discriminatory hiring and funding practices in schools. Forty-nine of the young men never made it home. Local police intercepted the buses and a shootout ensued. Six students died at the scene and 43 were kidnapped. The fate of only one of those 43 students is known for sure, with his bone fragments identified from a pile of ash that the government claims are the charred remains of all the students.

Who was responsible for this mass kidnapping? Alberto Díaz-Cayeros, Senior Fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies at Stanford University, declared “it was the state” when he gave the talk “Security and Political Authority in Guerrero, Mexico” at an event to explain the origins of this tragedy, hosted by UC Berkeley’s Center for Latin American Studies. The explicit and implicit failures of the Mexican government, in this case used synonymously with the idea of the state, led directly to the disappearance of these students. Díaz-Cayeros’s decisive answer reflects widespread public opinion in Mexico. “Fue el estado” (it was the state) has been an oft-invoked slogan in Mexico since September. According to a survey commissioned by the Mexican Chamber of Deputies in December 2014, the vast majority of respondents attributed high levels of blame to public officials and institutions. When asked to select whom they believed to be “very responsible” for this mass kidnapping, 73 percent indicated then-mayor of Iguala, José Luis Abarca, 46 percent indicated President Peña Nieto, and roughly 25 percent of respondents each indicated the Senate, the Chamber of Deputies, and the Army.

Beyond the role of the state apparatus and its guardians in this tragedy, instability in Guerrero has deep geographical roots. Guerrero has a long tradition of being a hotbed for insurrection, rebellion, and social change. Situated at the meeting point of two tectonic plates, a large mountain range spans the underbelly of the state as does the Balsas river, which runs parallel to the coast. With the indigenous populations of this area largely wiped out prior to Mexican Independence, low population density combined with these two important natural features have created large expanses of isolated and difficult to navigate terrain.

This region also has been historically contentious. Prior to independence, Guerrero was considered to be the land of muleteers, runaway slaves, and smugglers. Mexican Independence itself was finalized in Iguala, Guerrero, with the state’s namesake, Vicente Guerrero, meeting with fellow independence-seeker Agustín de Iturbide. Díaz-Cayeros asserted that while this unique history and difficult geography was not deterministic, this region has been ideal for the growth of guerrilla movements and rebellious activity, making it an unsurprising epicenter for the current controversy.

The particular school from which these disappeared students originated, the Escuela Normal Rural Raúl Isidro Burgos de Ayotzinapa, likewise has a strong history of political activism. Díaz-Cayeros describes the town of Ayotzinapa as being at the crossroads of the two distinct and powerful processes: large-scale drug trafficking to the west and endemic and profound poverty to the east. A byproduct of the effort in the 1920s to create more rural schools, the Raúl Isidro Burgos Rural Teachers College of Ayotzinapa itself was founded with the goal of being “belligerent.” This school, along with other rural teachers training colleges, was an integral part of the 1960s movement toward dismantling the system in which local political bosses, caciques, exercised arbitrary power in rural areas with little oversight. Powerful actors within the state of Guerrero have been at odds with students from the Ayotzinapa teachers college for decades. Its history of fighting for power redistribution is emblazoned on the walls of the school in the form of murals dedicated to rebels and insurrectionaries.

The fate of the students who boarded the buses to protest on that fateful September day is still largely unknown. Much of the evidence indicating that the disappeared were, in fact, killed comes from the tortured and coerced testimony of local police, bureaucrats, and members of the drug-trafficking organization Guerreros Unidos. The government claims that all 43 students are dead, having been killed at the hands of drug traffickers after the mayor of Iguala ordered local police to intercept the caravan of buses and turn them over to the traffickers. However, only the remains of one of the 43 have been identified.

One of the promises of independence, enumerated in the Sentimientos de la Nación, one of the most important documents of the Independence Movement, was that the security of Mexican citizens was the single most important social guarantee of the state. Díaz-Cayeros asserted that this promise was one of the most fundamental responsibilities of the Mexican state and the very reason why the state should be held responsible for the disappearance of the 43 students in Ayotzinapa. Despite historical and geographical conditions that made the region and this particular teachers training college likely spaces for contentious politics, Díaz-Cayeros attributes fault to a fundamental failure of the state to provide this promised security. In his assessment, while Mexico has the capacity to develop infrastructure, it lacks the fundamental capacity to guarantee security for its citizens. To Díaz-Cayeros, this failure is reminiscent of the dirty war of the 1970s in which more than 500 individuals were disappeared, and it is a clear sign that Mexico’s historic inability to protect its citizens persists to this day.

Where does this leave Mexico? Large-scale protests erupted in the capital and around the country in response to this mass kidnapping and likely mass murder. The Peña Nieto administration has made clear attempts to discredit protesters and destabilize the burgeoning social movement. Those arrested in the Zócalo in Mexico City were charged with terrorism, sedition, and attempted murder and held for 80 days in maximum-security prisons without being charged, according to Díaz-Cayeros. Yet, in his assessment of Mexico, he appears to be cautiously optimistic. Díaz-Cayeros emphasized that Mexico was a far cry from being a failed state and far better off than neighboring countries such as Guatemala. In the end, he concluded, despite intractable geography and a tumultuous history, “you can move mountains.”

Alberto Díaz-Cayeros is a senior fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute at Stanford University. He spoke for CLAS on February 4, 2015.

Tara P. Buss is a Ph.D. candidate in the Charles and Louise Travers Department of Political Science at UC Berkeley.