Translation is a way of deep reading, another point of entry after you’ve read a text more times that you can count. The first time I tried to translate the work of the beloved Brazilian writer Clarice Lispector was as a new graduate student in UC Berkeley’s Department of Comparative Literature. I wanted to understand one of her most puzzling stories, “O ovo e a galinha” (The Egg and the Chicken). The opening is simple enough — a woman looks at an egg on the kitchen table: “In the morning in the kitchen upon the table I see the egg. I look at the egg with a single gaze.” Yet as with most of Lispector’s writing, what begins as a concrete, objective thing slips from your grasp:

Translation is a way of deep reading, another point of entry after you’ve read a text more times that you can count. The first time I tried to translate the work of the beloved Brazilian writer Clarice Lispector was as a new graduate student in UC Berkeley’s Department of Comparative Literature. I wanted to understand one of her most puzzling stories, “O ovo e a galinha” (The Egg and the Chicken). The opening is simple enough — a woman looks at an egg on the kitchen table: “In the morning in the kitchen upon the table I see the egg. I look at the egg with a single gaze.” Yet as with most of Lispector’s writing, what begins as a concrete, objective thing slips from your grasp:

Immediately I perceive that one cannot be seeing an egg. Seeing an egg never remains in the present: as soon as I see an egg it already becomes having seen an egg three millennia ago. —At the very instant of seeing the egg it is the memory of an egg. —The egg can only be seen by one who has already seen it. —When one sees the egg it is too late: an egg seen is an egg lost.

My head is already swimming, and we haven’t even arrived at the chicken yet. The earliest version of this translation is written in pencil in a notebook somewhere, boxed up with the rest of my papers from the decade it took to complete my Ph.D.

I had no way of foreseeing that by the time I earned my degree, in fall 2015, I’d have made a two-year detour to translate the Complete Stories of the writer who was supposed to be the subject of my final dissertation chapter. Even now, after inhabiting “The Egg and the Chicken” to the point of claustrophobia, I can’t stop revisiting it, both in English and in Portuguese. I don’t think I’ll ever stop retracing the egg and the chicken in my mind.

“Be careful with Clarice. It’s not literature. It’s witchcraft.”

— Otto Lara Resende

Nearly 40 years after her death, the work of Clarice Lispector is not only required reading in Brazil, but she has also attained the status of mystic, sage, and glamorous literary icon all rolled into one. Her famously gorgeous face turns up on posters, graffiti murals, and lampshades, and a stunning variety of inspirational quotes are spuriously attributed to her on social media.Clarice, as she’s known in Brazil, has that effect on people. To echo a warning that her friend, the writer Otto Lara Resende, once gave to scholar Claire Varin: “Be careful with Clarice. It’s not literature. It’s witchcraft.” Clarice Lispector is a household name in Brazil, so famous that people use just her first name, like the soccer star Pelé, the singer Caetano, or former Presidents Lula and Dilma. You can discuss Clarice with taxi drivers and fruit vendors, particularly in Rio de Janeiro, the city where she spent most of her adult life and where they’ve recently installed a life-size statue of her by the beach in her neighborhood of Leme, just off Copacabana.

Like Mark Twain, J.D. Salinger, or Toni Morrison for Americans, Clarice Lispector is a writer who Brazilians often encounter as teenagers in school. Passages from Lispector stories regularly appear on the vestibular exam, the Brazilian version of the SATs. For every educated Brazilian, reading Clarice is a necessary rite of passage, with all that comes with it — a mix of intimidation and the potential oppressiveness of something compulsory, but also the ecstasy and wonder of discovering a voice that speaks to you like no other. Clarice’s writing is simple and complex in ways that defy explanation, even from the so-called experts: literary scholars.

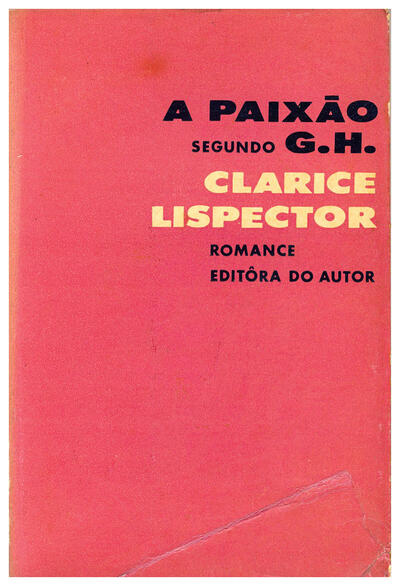

When the interviewer asks if she thinks future generations will better understand her, she replies, “I have no idea. I know that before, no one understood me, and now they understand me.... I think that everything changed, because I haven’t changed at all. As far as I know I haven’t made any concessions.” As for “The Egg and the Chicken,” she admits that it’s “one story of mine that I don’t understand very well,” and singles it out as among her favorites, “a mystery to me.”In the writer’s only televised interview, conducted in the last year of her life, Clarice mentions one of her most notoriously difficult novels, The Passion According to G.H., difficult for being an abstract, meandering, mystical meditation on the nature of existence, among other things. She says, “a Portuguese teacher at Pedro II [an elite high school in Rio] came to my house and told me that he’d read the book four times and still didn’t know what it was about. The next day, a 17-year-old girl, a college student, told me it was her favorite book.” Clarice then elaborates, “Either it touches you or it doesn’t. That is, I suppose that understanding isn’t a question of intelligence but rather of feeling and of entering into contact.”

What this exchange shows is that there are no ready solutions for how to read Clarice and even less for how to explain her. As I have found through translating her work and accompanying the range of new readings and responses to it, there are a variety of ways to rediscover her at different moments of one’s life. Clarice’s writing is playful and forbidding, deeply philosophical and slapstick, intensely psychological and sensual, dramatic but also plotless. One can read her as a late modernist, a Brazilian, a woman, a mother and the worldly wife of a diplomat, one of the first Brazilian women to earn a law degree, the child of poor Jewish refugees who fled the pogroms in what is now Ukraine, a Jewish writer with a strong Catholic influence, a spiritualist with a syncretic streak and interest in the occult, a mystic, a foreigner and outsider.

Clarice Lispector became a literary sensation at the age of 23 in 1943 with her first novel, Near to the Wild Heart, about the coming of age of a young woman named Joana who eventually leaves her husband. It drew comparisons to the stream of consciousness styles of Virginia Woolf, Katherine Mansfield, and James Joyce, from whose novel Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man Lispector plucked the title for her book. The next year, Lispector married one of her law school colleagues, Maury Gurgel Valente, who became a diplomat and with whom she would have two sons and live in Rome, Bern, and Washington, D.C., before divorcing him and moving back to Rio de Janeiro with their children in 1959.

From 1940 to 1977, Lispector wrote nine novels, more than 85 short stories, numerous newspaper columns and literary sketches known as crônicas, and four children’s books. She also translated from English and French, writers ranging from Agatha Christie, Jonathan Swift, and Edgar Allan Poe to Jules Verne and Bella Chagall. There were moments when Lispector fell out of favor and then was applauded again, yet by the time she died from ovarian cancer, on the eve of her 57th birthday in 1977, she had already achieved renown as one of her country’s most esteemed writers.

Translation plays a unique role in giving life to an author’s work beyond its original context, and Clarice Lispector has had many lives in English. Her writing is odd and challenging, and it has taken over 50 years for a more mainstream literary audience to appreciate her work in translation. It’s hard enough to convince the gatekeepers of publishing capitals — New York, London, Paris — to embrace writers with unfamiliar styles, even when backed by the cultural weight of canonical literary traditions, such as literature in French and German. It becomes harder still to convince them to invest their energies in a writer like Clarice Lispector, whose work comes out of a literary tradition considered minor and little known beyond its national context. Even within this tradition, Lispector’s style is less readily engaging than a writer’s like Jorge Amado, whose novels depict more vibrant characters and locales that better fit a foreigner’s idea of Brazilian “local color.”

Given the challenges to publishing unusual work by unknown writers, it is unsurprising that most of the earlier English translations of Lispector’s work were undertaken by university and small presses. In 1961, the University of Texas published the first translation of a Lispector novel into English, The Apple in the Dark. At the time, the translator, Gregory Rabassa, was more famous than the author, already associated with translating Latin American Boom writers, including Julio Cortázar and eventually Gabriel García Márquez.

The 1980s saw another wave of Lispector interest through feminist critique, after the influential French feminist philosopher Hélène Cixous wrote the first of several books rapturously elevating Lispector as the muse for Cixous’s theory of l’écriture féminine, feminine writing. Cixous’s attention led to a series of Lispector translations into French in the 1970s and ’80s by the feminist press Des Femmes. Cixous’s writing also prompted Lispector’s inclusion on the syllabi of Women’s Studies courses in the United States.

In the multicultural context leading into the 1990s, with interest in world literature on the rise, New Directions in the U.S. and Carcanet in England put out further translations of Lispector’s work, the majority translated by the Scots-Italian professor Giovanni Pontiero, whose employer, the University of Manchester, originally housed Carcanet. Another university press, Minnesota, put out The Passion According to G.H. in 1988 and Àgua Viva in 1989, which Professors Earl Fitz and Elizabeth Lowe translated as Stream of Life. By that time, Lispector was well-known among those familiar with Latin American literature and feminist theory. She also became a cult favorite in creative writing MFA programs, since along with literary scholars, it’s the poets and writers who make it their business to sniff out undiscovered literary gems.

The previous generations of Lispector scholars and translators laid the groundwork for her ready entry into the international literary canon. Yet the level of “Lispectormania” that the latest series has inspired is unprecedented. This renewed interest began in 2009, when Benjamin Moser published the first English-language Lispector biography, Why This World. Its success led New Directions to launch a series of new Lispector translations, starting with her final novel, The Hour of the Star, in 2011. Momentum picked up with the simultaneous release of four novels in 2012. It culminated in the publication of the Complete Stories in August 2015, which made the cover of the New York Times Sunday Book Review, the first time a Brazilian author has gained that distinction.

The attention reverberating from New York induced Lispector’s Brazilian publisher, Rocco, finally to print her complete stories in the original, Todos os contos, with the same cover and design as the U.S. edition. New Directions plans to release new translations of the remaining four novels over the next few years and eventually volumes of the crônicas, letters, and children’s books, assembling a Complete Works of Clarice Lispector.

What we might call the fourth wave of Lispector in English has granted the writer an unprecedented level of prominence on the world literary stage in a way that has brought her reputation much closer to what it is in Brazil. Recent critics have grasped for ways to comprehend the shock of a talent they were previously blind to. They have sought to locate Clarice in the international canon by comparing her to a dizzying range of writers, including Kafka, Borges, Nabokov, Chekhov, Woolf, Joyce, Sartre, Wittgenstein, Gertrude Stein, Edith Wharton, Ovid, Rabelais, and even Groucho Marx.

After a certain point, these comparisons form an absurd composite, yet they’re also a sign of how far-reaching Clarice’s writing is. One reviewer wrote, “This welcome, overdue publication of the Complete Stories of Clarice Lispector fills a hole in our literary history that many of us didn’t even know existed.” Another referred to Lispector’s sudden popularity as “the Bolaño treatment,” referring to the explosive popularity of Chilean writer Roberto Bolaño after The Savage Detectives came out (though I’d say that Lispector’s books don’t quite have Bolaño’s bestseller appeal). In general, it’s a great time for literature in translation, with Karl Ove Knausgaard becoming a literary rock star, Ferrante Fever still running high, and new independent translation presses sprouting up every year.

In the past two years, I’ve paid close attention to how this rediscovery of Clarice Lispector has been filtering into the Anglophone literary world. She is gradually moving away from qualifiers like “the great Brazilian writer,” “the greatest Jewish writer since Kafka,” “a female Chekhov,” and “the Brazilian Virginia Woolf,” and into a new space where writers in English drop casual references to just “Clarice Lispector,” “Lispector,” or “Clarice,” with the assumption that readers should already know who she is. She is increasingly read beyond strictly Latin American and feminist frameworks, now integrated into English classes at American universities and high schools.

Clarice keeps invading contemporary North American poetry, fiction, and theater, with talk of film adaptations in the air. I think about the day when postcards of the glamorous Clarice Lispector appear next to those of Virginia Woolf, Joan Didion, and Simone de Beauvoir in bookstores and wonder whether it will be a sign of literary triumph or cultural decadence.

|

Translation as performance: Original: “Então tive a prova, a duas provas; de Deus e do vestido.” Literal translation: “So I had proof, the two proofs; of God and the dress.” Dodson: “So I had fitting proof, the fitting and the proof; of the dress and of God.” — from Clarice Lispector, “The Dead Man in the Sea at Urca” |

While translating the Complete Stories, I focused especially on capturing Lispector’s cadences that carry the reader through the obstacles of her odd grammar and diction. I also found a way to enter her work less as a scholar chasing an ideal of precision in literary interpretation and rather as a performer aiming for another sort of interpretive accuracy. As a translator, instead of explaining what you think the writer means, you need to perceive what she’s doing in order to recreate its effect. Translations are often praised for their seamlessness, for making the work seem originally written in the target language. If attributes like fluidity and harmony belong to ideals of beauty in a major mode, then what these new translations are more attuned to in Lispector’s work is an embrace of an aesthetic counterpart in a minor key, marked by a more deviant logic of interruptions, erratic movements, and jarring juxtapositions. I view the effect as similar to the way Emily Dickinson’s poetry gained a greater force of individual genius after being restored to her more daring punctuation, word choices, irregular meter, and slant rhyme, after being initially rendered more conventionally by Thomas Wentworth Higginson and Mabel Loomis Todd when they edited her work posthumously.While countless factors have contributed to the growing influence of Clarice Lispector’s work in English, I believe that the definitive element has been the approach of these new translations, which hew closer to her unique style and way of distorting standard Portuguese. Of course, I’m slightly biased, as the sixth translator in this series, all of us working closely with the same editor. We each have our idiosyncrasies and different inflections of English — from different U.S. regions, England, and Australia — yet Lispector’s voice maintains coherence throughout.

In my Translator’s Note, I compared the process of translating a lifetime of work in two years’ time to “a one-woman vaudeville act.” While Lispector’s voice is incredibly distinct, she takes on a dizzying range of personas and voices, which I breathlessly accompanied in these stories. And her voice continues to be refracted and multiplied, through additional translations into English, as well as into Hebrew, Greek, Ukrainian, Dutch, and Korean, among others. On and on those ovos and galinhas roll, the egg and the chicken in constant evolution as we keep rediscovering Clarice.

Katrina Dodson holds a Ph.D. in Comparative Literature from UC Berkeley and is the translator of the Complete Stories by Clarice Lispector (New Directions, 2015), for which she was awarded the PEN Translation Prize in 2016. Dodson spoke for CLAS on March 8, 2017.