Dictatorial regimes are fueled by arrogance and by the ability to deny that their power will ever end. Under such a regime, a vast array of social actors — armed forces, intelligence services, religious institutions, the business sector, and mass media — will rely on a system of secrets and lies after the real (or apparent) end of the dictatorship.

When questioned about the application of brutal state policies (fear, repression, torture, summary execution, disappearance), they deny these actions ever happened. When challenged, they simply dispute the charges. By refusing to tell the truth, they boycott — on a daily basis — the society in which they live. To the dehumanization caused by the violence they inflicted, they now add the denial of what they did. And I wonder, what are the limits of this dehumanization? Were the pain and the suffering inflicted not enough?

This article examines how systems of secrets and lies generated during conflict and in post-conflict contexts affect victims’ transitional rights — their rights to truth, justice, reparations, and non-repetition. It focuses on Chile’s transitional period and, more specifically, on the pursuit of accountability for the torture and extrajudicial execution of the popular folksinger Víctor Jara in September 1973.

A System of Secrets and Lies

On September 11, 1973, under the leadership of General Augusto Pinochet Ugarte, officers of the Chilean Army initiated a coup d’état to oust President Salvador Allende. Following the army’s assault on the city of Santiago and the capture of the Palacio de La Moneda — the presidential residence where Allende would take his own life — a junta of four military commanders seized control of the country and appointed Pinochet as president and commander-in-chief. The coup put an end to the history of constitutional democracy in Chile and subjected the country and its people to a dark period of repression, disappearances, and death that lasted nearly two decades.

For years, historians, lawyers, judges, filmmakers, politicians, and journalists have worked to reconstruct and recount the story of the coup, especially its first 72 hours. Relevant information and documentation about the initial meetings in the Ministry of Defense (where the most important decisions related to the coup were made) and the events in the Palacio de La Moneda are even found in the archives of declassified documents in the United States.

Until recently, however, we lacked sufficient information about the detention centers and other infrastructure, such as the Estadio Nacional de Chile, where people perceived as Allende loyalists were detained and exterminated. As the enemies of the new Chile that the coup sought to create, these so-called “subversives” were targeted by a large-scale system of violent repression against opposition and dissent implemented by the military junta. The first hours of dictatorial authority were devoted to hunting down sympathizers of the previous government, including public officials and politicians of various stripes, intellectuals, academics, students, and artists.

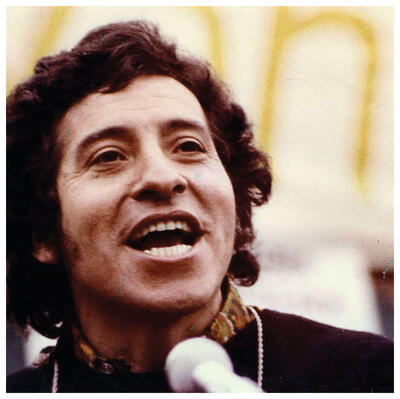

Víctor Jara was a popular songwriter and democratic activist who advocated for social justice and the protection of the working class and indigenous culture. He personified the ideological enemy of the new right-wing military command. Jara was brutally tortured in the Estadio Nacional and died on September 15. His lifeless body was found in a pile of corpses, his hands and wrists broken, and his body riddled with 44 bullet wounds. He was 40 years old at the time of his execution.

Jara was just one of the thousands of victims of the post-coup repression at the Estadio Nacional and of the massive systematic policy of violence and torture in Pinochet’s Chile. The Rettig Report, drafted in 1990 by the National Commission for Truth and Reconciliation, estimated that 2,279 persons had been killed or disappeared under the Chilean regime. By 2004, the Valech Report from the National Commission on Political Imprisonment and Torture had documented 27,255 cases of arbitrary detention and torture. More than 5,000 of these victims were detained between September 11 and 13, 1973.

Widely studied and analyzed, the Chilean coup has become pivotal for understanding 20th-century Latin America. Yet, most readers are unfamiliar with the failed attempt to overthrow Chile’s democratically elected government three months earlier in June 1973. The men responsible for organizing this first coup came from various branches of the army. Upon discovery of their plot, they were arrested and imprisoned.

The fate of these men opens a chink in Chile’s carefully crafted system of lies. It has recently come to light that one of General Pinochet’s first orders as leader of the coup was to pardon the men who had been arrested during the June 1973 coup attempt and to assign them to guard the Estadio Nacional. The level of cruelty and violence described by numerous surviving prisoners of the stadium — both men and women — can be explained in part by the anger these officers felt after their recent punishment under the Allende government.

Likewise, it is no coincidence that, of all the regiments in all the regions of the country, Pinochet ordered the Tejas Verdes regiment to move to the Estadio Nacional, where they would assist the Blindados No. 2, Esmeralda, and Maipo regiments in overseeing the imprisonment and torture of detainees. Just a few days after the coup, the head of the Tejas Verdes regiment, Colonel Manuel Contreras, became the cruel and creative director of the Dirección de Inteligencia Nacional (DINA, National Intelligence Directorate).

No one ever heard about these and other covert actions: they were hidden, then denied, and finally, passed off as lies. Yet, the Chilean military didn’t lie until after Pinochet was arrested in London in 1998 because they had no need. No one questioned them, there were no international demands, and the victims — the thousands of Chileans affected by the dictatorship — were irrelevant. Chilean military officers only started lying and hiding after the first lawsuits were filed, and then, they followed the same systematic patterns they had used when torturing and executing detainees. Today, despite some progress, the Chilean Armed Forces insist on maintaining a conspiracy of silence, a sort of prolonged repression that continues to subjugate the citizens they claim to protect and serve.

In the midst of so many secrets and lies, only one group finally decided speak out and end the complicitous silence: a relatively small troop of conscripted soldiers who were completing their compulsory military service in September 1973 and had the misfortune of belonging to the detail that was moved to Santiago to support the coup.

Today, these soldiers are fishermen, accountants, security guards, concierges, and taxi drivers, who live in different parts of Chile. They decided, both individually and collectively, to tear down the web of lies. Thanks to the testimonies of these men, whose names were unknown until recently, we have been able to identify clandestine torture centers (now transformed into fancy apartment buildings in the middle of Santiago). We have likewise learned some of the rationale behind the harrowing nights following the coup d’état, because the conscripts were also involved in the crimes.

Torture and Execution

One of the conscripts who stepped forward to bear witness was José Paredes. In his testimony, Paredes identified Lieutenant Pedro Pablo Barrientos Núñez as a participant in the torture of Víctor Jara and the man responsible for the shot that killed him. In 1973, Barrientos was a section commander in the Second Combat Company of the Tejas Verdes regiment of the Chilean Army stationed in the Estadio Nacional. In 1989, after the end of Pinochet’s rule, Barrientos moved to the United States. He was a naturalized American citizen, residing and operating businesses in Florida, when he went to trial for the torture and execution of Jara.

Hugely famous throughout Latin America for his moving protest songs and stalwart defense of indigenous rights, Víctor Jara was working as a theater professor for the Universidad Técnica del Estado (UTE) when the coup took place. At the time, he was preparing a music festival on the UTE campus, where Salvador Allende planned to call for a plebiscite in response to demands aired in recent demonstrations throughout Chile.

On September 12, 1973, after hearing about the coup, Jara went to the university, where he was detained. He was transferred to the Estadio Nacional, along with hundreds of university students, administrators, and professors. A gloomy structure in a central Santiago neighborhood, the Estadio Nacional is a classic example of the cold, impersonal architecture of the 1960s. For a stadium, it’s rather small — very small when one considers that during the first two days of the coup, it was transformed into a detention center where more than 5,000 people were held.

A military intelligence officer, Captain Fernando Polanco Gallardo, identified Víctor Jara when he was being transferred from the UTE to the Estadio Nacional. Polanco separated Jara from the rest of group and beat him severely. During the next three days, Jara was held in the stadium, and on September 15, he was taken to an underground locker room, where he was interrogated and tortured as a punishment for his political beliefs and, finally, executed.

Seeking Justice

In May 2012, just few hours after my son Diego was born, I received a surprising message. My colleague Francisco Ugas was working with a group of Chilean prosecutors specializing in human rights, and they wanted my help with one of the many criminal cases filed during Chile’s transition process after Augusto Pinochet’s arrest in London. This case addressed the execution of the folksinger Víctor Jara.

In our first meeting, the Chilean prosecutors and I explored our options; we soon decided to form a legal team that would use U.S. law to help Víctor Jara’s family — his widow, Joan Jara, and her daughters, Amanda and Manuela — file a civil lawsuit against Barrientos for Jara’s brutal torture and summary execution in the Estadio Nacional. Our final goal was Barrientos’s extradition to Chile, where he would have to face criminal trial.

The U.S. lawsuit against Barrientos was originally filed in September 2013 on behalf of Víctor Jara’s family. Our complaint maintained that the former Lieutenant Pedro Pablo Barrientos Núñez had participated in the arbitrary detention and torture of Víctor Jara. Our complaint also alleged that Barrientos was responsible for cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment and extrajudicial killing, as well as crimes against humanity, since the death of Víctor Jara was part of a widespread and systematic attack against intellectuals, political leaders, and Allende supporters that took place in mid-September 1973. We defined this violence as “systematic” because members of the army who were deployed in the stadium operationalized their actions against the subversives, with each soldier being assigned a task. For example, Barrientos was in command of the mass detentions at the Estadio Nacional, and he also took command of and exercised direct control over soldiers in the stadium. Barrientos’s liability thus derives from the principles of direct responsibility, conspiracy, and aiding and abetting, as well as command responsibility, since he and members of the Chilean Army under his command committed the acts that led to Jara’s torture and death.

In December 2012, while we were still preparing to go to court in the U.S., a Chilean court indicted Barrientos and nine other members of the Chilean security forces for their alleged responsibility in the torture and assassination of Víctor Jara, yet U.S. authorities failed to extradite Barrientos to Chile for criminal prosecution. Therefore, a complaint under the Alien Tort Statute (ATS) and the Torture Victim Protection Act (TVPA) before a U.S. court was the only option that would let Jara’s family learn the truth of what had happened in the Estadio Nacional and help them pursue even a portion of the justice that they had been denied for decades. In the U.S., this sort of lawsuit doesn’t lead to the imposition of a criminal sentence, but the court must examine the evidence and determine the defendant’s responsibility for the crimes committed and award compensatory and punitive damages.

After two years of investigation, the trial against Barrientos started in a U.S. district court in Orlando, Florida, on June 13, 2016. Witnesses brought to trial, particularly the key conscripts from the Chilean Army, testified that Pedro Pablo Barrientos Núñez was at the Estadio Nacional between September 12 and 15, 1973; that he gave orders to the Second Company of the Tejas Verdes regiment as its second-highest-ranking officer; and that he bragged about having shot Víctor Jara in the head. At the stadium, he was in command of the guards, oversaw interrogations, and met with the heads of the detention center.

The testimonies of these conscripts also provided a better understanding of the horrors endured throughout the Estadio Nacional. The trial exposed the systematic practices of torture in this mass detention center. The conscripts described the professors’ naked bodies, the suicides provoked by the torture victims’ screams of pain; the summary executions — even of children — and the massacres of those who tried to flee. To inspire even greater fear, the detainees were shown piles of corpses that were later removed in refrigerated trucks. Witnesses also narrated the brutality of Jara’s torture, recounting how officers at the Estadio Nacional broke Jara’s wrists and hands to make sure he would never play his guitar again.

After nine intense court sessions, on June 27, 2016, the jury found the defendant, Pedro Pablo Barrientos Núñez, liable for both the torture and extrajudicial killing of Víctor Jara. Two days later, on June 29, 2016, the district judge ordered Barrientos to pay $8 million in compensatory damages and $20 million in punitive damages (plus court costs) to the Jara family.

More Secrets and Lies

In post-conflict and post-dictatorship processes, the right to know the truth about what happened is one of the most basic rights of the victims. Indeed, truth has become a salient issue in these periods of transition, as seen in the creation of the iconic South African and Latin American truth commissions.

The concept of truth is so relevant in current transitional processes that it is addressed explicitly in the recent peace accord between the Government of Colombia and the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC, Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia). Point five of the accord defines the rights of the victims of the Colombian conflict and creates an institutional system to guarantee the process of transitional justice in the country. Likewise, this transitional system — the Comprehensive System of Truth, Justice, Reparations, and Non-Repetition — includes two extra-judicial institutions directly related to the search for truth: the Truth Commission and the Special Unit for Disappeared Persons. The judicial system, the Special Jurisdiction for Peace, also provides for reduced criminal sanctions if perpetrators recognize the truth of what happened and their responsibility for the crimes.

These truth mechanisms seek to discover what happened to the victims, to create narratives about the roots of conflict, and to help societies understand the causes of structural violence. Designed in response to victims’ and families’ demands to know the fate and whereabouts of their loved ones, they strive to put an end to their search for answers and provide a kind of closure to their suffering. These efforts to know the truth endeavor to counterbalance the systems of secrets and lies that usually arise in post-conflict situations, the conspiracies of silence among members of the elite and other social sectors involved in the commission of abuses.

The case of Víctor Jara is representative of such a system of secrets and lies in Chile. In the search for justice, Jara’s family had to overcome various forms of denial — institutional, legal, social, individual — as I discuss in the following paragraphs.

After her husband’s death, Joan Jara began looking for the truth. She wanted — and deserved — to know what had happened to Víctor, why he was tortured and killed in such a brutal manner, and who was responsible for his death. In 1978, Joan Jara asked the Chilean authorities to open a criminal investigation into her husband’s death. The Criminal Court of First Instance started to investigate the events, but after four years, it concluded that there was insufficient evidence to initiate prosecution, so it closed the investigation. Despite exhausting every legal process available in this search for justice, the institutionalized lack of transparency and repression of the Pinochet regime hid the truth and impeded the pursuit of accountability.

This institutionalized system of secrets became a legal form of denial in 1978, when the Chilean regime passed the Amnesty Law. According to the Rettig Report, the law allegedly aimed to strengthen “the bonds uniting the Chilean nation, leaving behind hatreds that are meaningless today,” yet it guaranteed that “all human rights violations committed prior to the date of that decree would remain in impunity,” noting that the law applied to all persons who had committed criminal offences during the state of siege between September 11, 1973, and March 10, 1978, which was the period of “the worst and most systematic human rights violations perpetrated by the military government.” The justification used to pass the Amnesty Law is a common narrative of denial in (post-)autocratic contexts that portrays silence and oblivion as necessary to achieve peace and stability.

The Chilean dictatorship’s opacity even transcended the end of Pinochet’s tenure. On October 5, 1988, after 15 years of authoritarian military rule, a majority of Chilean citizens voted “No” in the national plebiscite to determine whether Augusto Pinochet should remain in power for another eight years. Yet even as the plebiscite put an end to Pinochet’s regime, the 1978 Amnesty Law was still applied, protected by the overwhelming power of the Chilean military. This broad and illegal amnesty impeded any form of accountability for the crimes committed, including the torture and assassination of Víctor Jara.

This impunity reigned until 1998, when Augusto Pinochet was detained in London following an arrest warrant issued by the Spanish judge Baltasar Garzón, who was applying the principle of universal jurisdiction to investigate international crimes committed during the Chilean dictatorship. While UK authorities rejected Pinochet’s extradition, thus allowing him to avoid criminal trial in the Spanish National Court, his arrest had a significant impact on the Chilean judiciary and threatened the sacrosanct system of secrets and lies. Only after Pinochet’s arrest and his subsequent return to Chile did the Chilean Supreme Court limit the scope and application of the Amnesty Law. Prosecutions finally began, even though the Amnesty Law remained in force until September 2014, another 16 years.

In this context, Joan Jara filed another complaint on the death of her husband with the Chilean Court of Appeals, and in 1999, this court initiated its investigations. But after 20 years of blatant institutional impunity and after having overcome the insurmountable effect of the Amnesty Law, the case of Víctor Jara found yet another challenge: the social pact of silence maintained by those who had personally witnessed or had knowledge of his torture and execution.

Regardless of the specific reasons for their silence and denial, the resistance of witnesses and participants to provide testimonies to the press, the courts, and society at large resulted in Víctor Jara’s case being closed once again in 2008. Leads dwindled to rumors, and lies shored up alibies. Then, just when the family’s desperation was reaching unprecedented levels — and the web of silence and lies was more intricate than ever — the small group of conscripts came forward to provide critical evidence that was previously unavailable.

Although José Paredes had identified Pedro Pablo Barrientos Núñez as the person responsible for Jara’s death in 2009, Barrientos’s whereabouts remained unknown until 2012, when an investigative report by the Chilean television station Chilevision revealed that Barrientos was in Florida. At that moment, Joan Jara decided to file the civil complaint before the District Court of Orlando, just as the Santiago Court of Appeals charged Barrientos as a direct perpetrator in the killing of Víctor Jara, pending extradition that was never implemented.

Over the course of these investigations, José Paredes, the soldier who identified Barrientos, changed his testimony on several occasions. I am not sure whether he was afraid or intimidated — or perhaps he had lied in his original testimony. What I know for certain is that he is alone, as are the other former soldiers who decided to speak out. They are the only ones who have revealed some of the truth, without any support, recognition, or help, and today, they feel demoralized.

Thanks to Chile’s system of secrets and lies, the perpetrators of such crimes have enjoyed long-lasting impunity, while the victims have been deprived of their rights to truth and justice for decades. It took Jara’s family more than 42 years to discover the truth and achieve a limited form of justice in a civil trial. Nonetheless, Chile continues its path to expose the truth of what happened. Democracy strives to overcome institutional silence; international pressure has ended legal impunity under the Amnesty Law; a handful of brave citizens have opened a window of hope against the social pact of silence; and now, the legal system has been able to prove the falsehood of individual accounts. The final form of denial the Jara family had to confront was individual in nature and took place in court. During the trial in Florida, despite extensive evidence proving his responsibility, Barrientos continually denied the allegations against him. Defense witnesses provided contradictory and inconsistent explanations about the former army officer’s activities, their communications with him, and his whereabouts in the days after the coup. Defendants are not expected to confess their responsibility in court, but Barrientos’s profound and irrational prevarication, his bizarre and grotesque fabrications, are symptomatic of Chile’s decades-long system of secrets and lies. Barrientos denied being present at the Estadio Nacional, even though witnesses saw him at the stadium more than 20 times in the four days following the coup and described him giving orders and participating in the abuses. This strategy of denial was at its most outrageous when Barrientos declared that he hadn’t heard about what had happened to Víctor Jara until 2009.

Towards a Conclusion

Like so many others in Chile, Spain, Colombia, Sri Lanka, Ecuador, and Guatemala, Joan Jara and her daughters spent decades attempting to untangle a web of lies, not only for themselves, but also for their extended families and for their countries. They have put the objectivity of their suffering at the service of the fight for truth and justice, the only way — I believe — to truly rebuild a country and provide the best for its people.

The trial against Barrientos exposed the truth about the execution of Víctor Jara and the atrocities in the Estadio Nacional. If justice prevails, Pedro Pablo Barrientos Núñez will be extradited to Chile, where he will face the Chilean people and his very presence will trouble those who attempt to preserve their power through lies.

In July 2015, while attempting to reconstruct what had occurred in the Estadio Nacional, and specifically to Víctor Jara, I interviewed 21 of the conscripted soldiers

in locations throughout Chile. Being with them re-minded me of carefully listening to my grandparents’ stories about the Spanish Civil War and Franco’s dictatorship. Once again, I felt the weight and the excessive price of building a society on the pillars of exclusion and lies. The challenge for all societies, including that of Chile, is to not desire or perpetuate a power that is based on lies, but to dare to build an inclusive society that can overcome them.

Almudena Bernabeu is the Co-founder and Director of Guernica 37 International Justice Chambers and has worked in human rights and international law for more than 20 years. She spoke for CLAS on September 19, 2016.