When I first heard that Diego Luna had directed a movie about the life of farm worker leader Cesar Chavez, I wasn’t quite sure what to think. To be clear, I, like many other starry-eyed fans, love Diego Luna: his mischievous half-grin, nonchalant scruff, and shaggy flop of hair. And I enjoy his films, too: “Y Tu Mamá También,” “Miss Bala,” “Rudo y Cursi,” to name just a few. But my doubts didn’t have anything to do with his body of work. I just wasn’t sure he’d be able to pull off a movie about such a triumphant moment — and movement — in our recent past. However, after watching an advanced screening of the film sponsored by UC Berkeley’s Center for Latin American Studies, I admit, happily, that I was wrong.

Luna’s modestly funded film, which took years of fundraising to complete, chronicles the life of Cesar Chavez, the Arizona-born co-founder of the United Farm Workers Union (UFW) who famously boycotted the grape industry and led a 300-mile march from Delano to Sacramento, California. Rather than tell the entire story of the California activist’s life, the movie focuses on a moment in history: Chavez’s efforts to unionize underpaid, overworked Latino farm workers in the Central Valley in the 1960s. Chavez, a farm worker himself, who worked in the fields until the late ’50s, galvanized Latino grape pickers to protest for higher wages and fair working conditions after witnessing the Delano grape strike called by Filipino-American farmworkers on September 8, 1965.

Their demand for livable salaries pushed Chavez and other key activists, like UFW co-founder Dolores Huerta, into action. On March 17, 1966, in an attempt to raise public awareness about the farmworker’s plight, Cesar Chavez and fellow strikers undertook a 300-mile pilgrimage from Delano to the state’s capital in Sacramento. They also encouraged all Americans to boycott grapes, striking a blow to profitable growers. Chavez and other strikers pushed forward for five years until the farmers finally agreed, in the spring of 1970, to sit down at the bargaining table. Growers hard-hit by the boycott signed contracts with the union, and since their grapes were union-approved, they sold for premium prices across the country. This increased pressure on other growers and eventually led the large growers to sign contracts with the union, giving workers higher wages, union representation, health insurance, and safety limits on the use of pesticides in the fields.

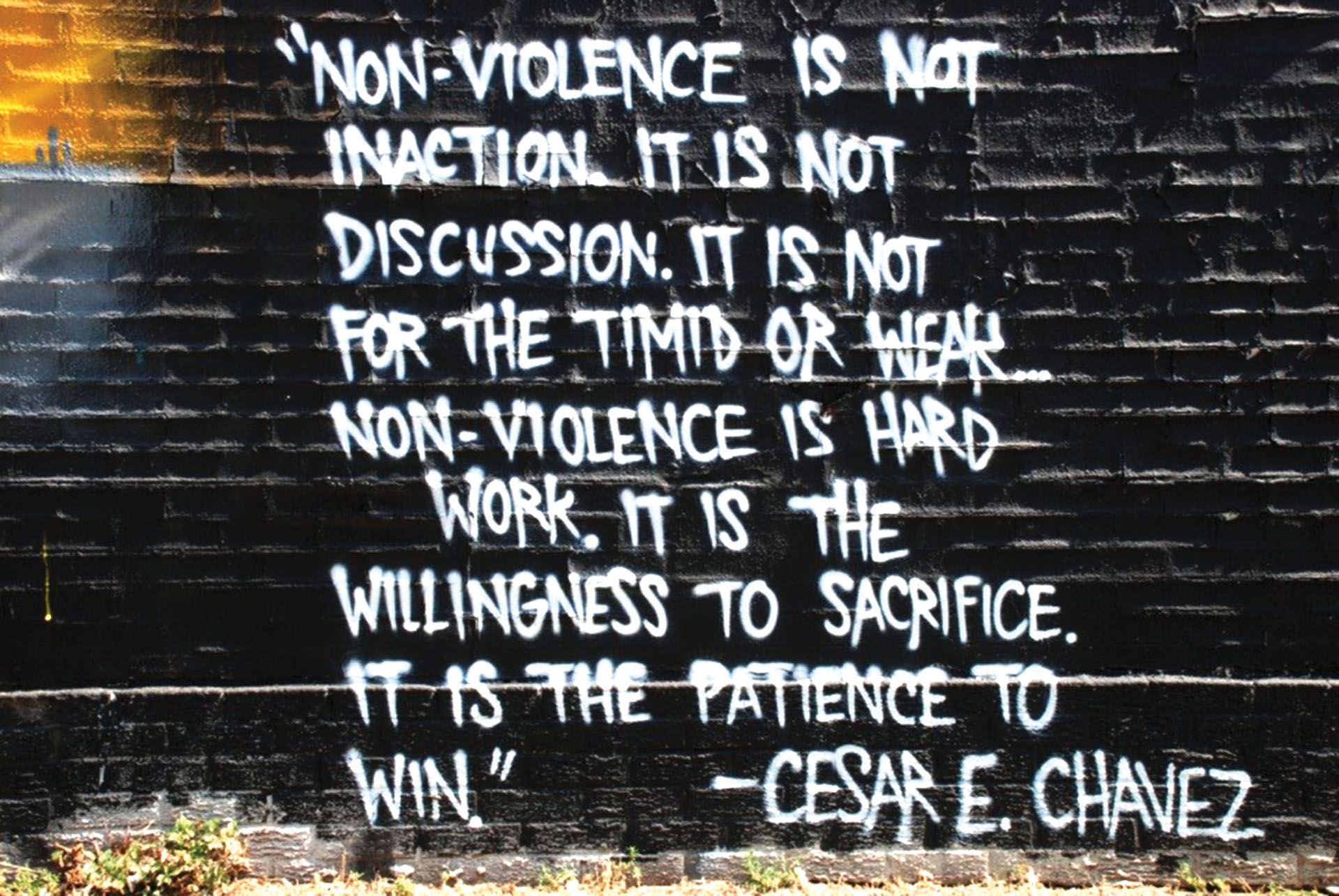

But the struggle to earn better working conditions and wages did not come without its sacrifices. The film depicts the brutal, 25-day hunger strike that Chavez undertook in 1968 in order to rededicate the movement to nonviolence as well as the alienation of his brooding teenaged son, who is often roughed up and hassled at school due to the activism of his father. These tensions helped dramatize the movie’s storyline, which was about the personal as much as the political. Some of the more critical reviews of the film have said that Luna’s Chavez was painted as a sanitized saint, cast in a glowingly reverential light. But I didn’t find him to be saturated with well-meaning sanctity. In fact, as the film reveals, the father of the movement was not always the family man he could have been, prioritizing his work over his family. And the rest of the characters in the cast weren’t perfect, either. Yes, they were certainly movers and shakers, but they weren’t, thank God, martyrs — how boring it is to watch perfect characters glide through life’s miserable obstacles — and how much more relatable to watch people, not heroes, do remarkable things.

Chavez’s family members had complicated relationships and gnawing self-doubts; some men in the movement were afflicted with machista swagger, occasionally throwing punches that undermined their leader’s trademark nonviolent philosophy. Sure, Luna could have imbued the film’s protagonists with a more radical, tortured bent, but I think the point of the movie was much simpler — to shed light on an overlooked chapter of our history — rather than explore the fracturing of a movement and the inner demons of its leader.

The preview audience seemed to agree. After credits rolled, the film received a standing ovation at Berkeley’s California Theater. One woman cupped her hands around her mouth and screeched, “Si se puede!” while a thunderstorm of claps rumbled throughout the room. Dolores Huerta was sitting two seats away from me — small-boned, with a shiny black bob and a presence much larger than her petite frame. Nearby, other original members of the UFW, who had marched to Sacramento with Chavez, were also seated, as was the current president of the organization, Arturo Rodriguez.

Viewers jeered and groaned when old footage of Reagan and Nixon popped onscreen and hooted gleefully during the film’s triumphant moments. I must admit that a few scenes in the movie did give me chills: it was thrilling to be watching that movie surrounded by the folks who birthed the movement in the first place. No matter what the cynics and jaded naysayers declare — the ones who shrug off activism because the system is damn corrupt anyway — watching the film in that theater was a profoundly moving experience. It was raining bitterly outside, and there I was, for the first time in months, inspired. The film is truly a must-see for anyone seeking to be reminded of one of history’s simpler lessons: if you want to change the future, it helps to study the past.

CLAS showed an advanced screening of “Cesar Chavez” on March 5, 2014. After the film, Diego Luna, the director; Arturo Rodriguez, president of the United Farm Workers, and Maria Echaveste of Berkeley Law responded to questions from the audience.

Erica Hellerstein is a student in the Graduate School of Journalism at UC Berkeley.