We’ve been told repeatedly over the past generation — and especially since 9/11 — that the world is more complicated than it used to be. The bipolarity of the Cold War is gone for good, and even a term like “multi-polar” seems naively tidy for an unprecedented and bewildering global era increasingly driven by nongovernmental organizations, multinational corporations, terrorist networks, insurgent groups, tribal councils, warlords, drug cartels and other non-state actors and organizations. Our times may be baffling, but they are hardly unprecedented. States have always shared the international arena with non-state actors. However, abetted by professional historians, states have usually promoted international narratives that leave non-state actors trivialized, distorted or ignored altogether.

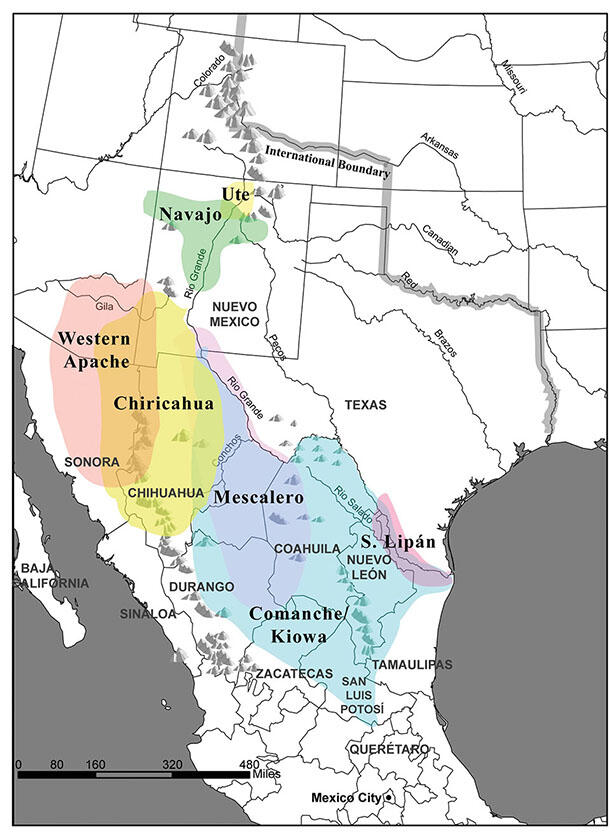

Consider the U.S.–Mexican War of 1846 to 1848. Historians on both sides of the border have framed the war as a story about states. They’ve crafted narratives of the conflict with virtually no conceptual space for the people who actually controlled most of the territory that the two counties went to war over: the Navajos, Apaches, Comanches, Kiowas and other independent Indian peoples who dominated Mexico’s far north. These native polities are invisible, or at best trivial, in history books about the U.S.–Mexican War, Manifest Destiny and Mexico’s own early national period.

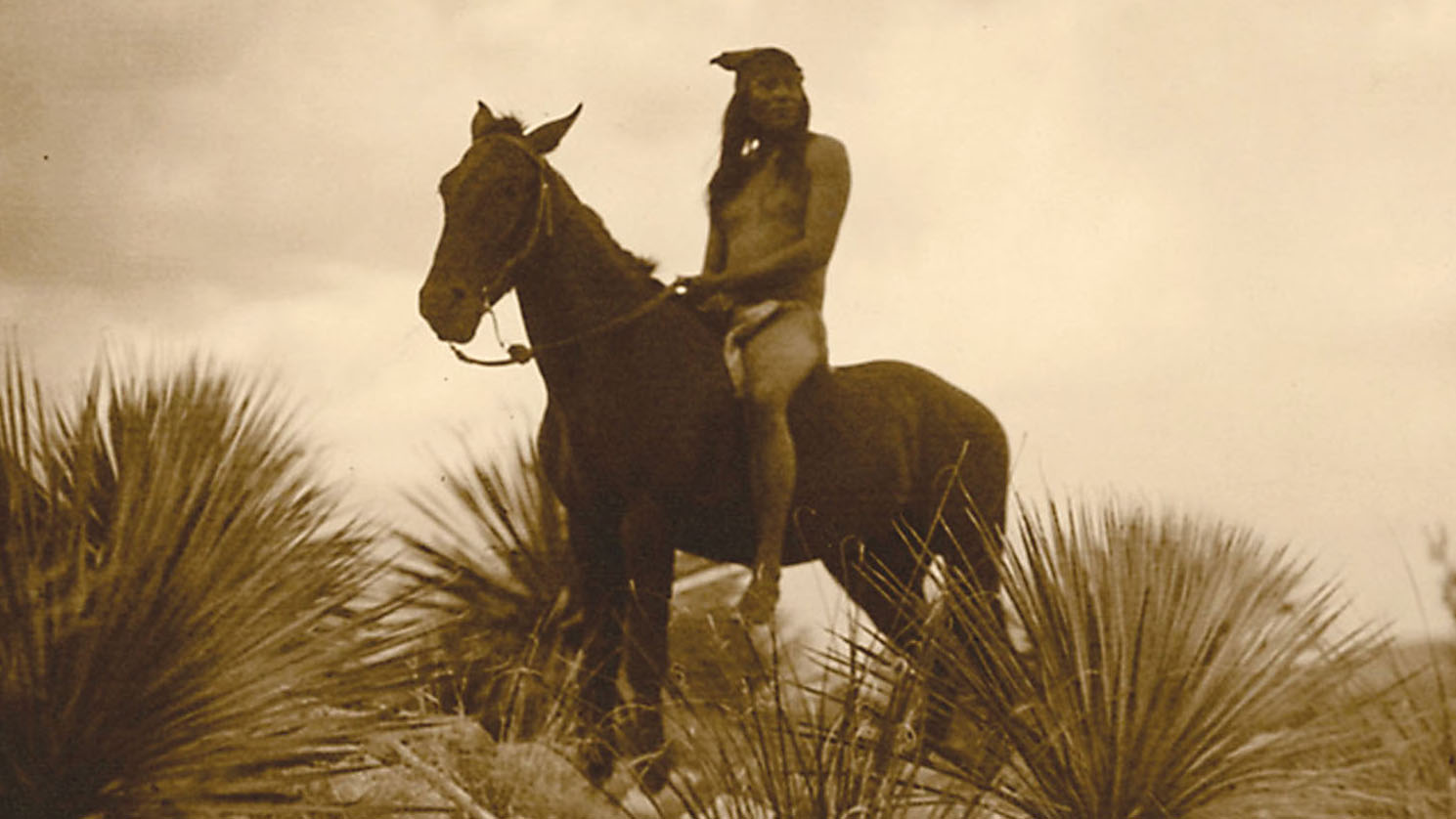

This fact testifies to a colossal case of historical amnesia because Indian peoples fundamentally reshaped the ground upon which Mexico and the United States would compete in the mid-19th century. In the early 1830s, Comanches, Kiowas, Navajos and several tribes of Apaches abandoned imperfect but workable peace agreements that they had maintained with Spanish-speakers in the North since the late 1700s. They did so for complex reasons that varied from group to group, but declining Mexican diplomatic and military power and expanding American markets were the backdrop for the region’s overall plunge into violence. Groups of mounted Indian men, often several hundred and sometimes even a thousand strong, stepped up attacks on Mexican settlements. They killed or enslaved the people they found there and stole or destroyed animals and other property. When they could, Mexicans responded by doing the same to their Indian enemies.

This fact testifies to a colossal case of historical amnesia because Indian peoples fundamentally reshaped the ground upon which Mexico and the United States would compete in the mid-19th century. In the early 1830s, Comanches, Kiowas, Navajos and several tribes of Apaches abandoned imperfect but workable peace agreements that they had maintained with Spanish-speakers in the North since the late 1700s. They did so for complex reasons that varied from group to group, but declining Mexican diplomatic and military power and expanding American markets were the backdrop for the region’s overall plunge into violence. Groups of mounted Indian men, often several hundred and sometimes even a thousand strong, stepped up attacks on Mexican settlements. They killed or enslaved the people they found there and stole or destroyed animals and other property. When they could, Mexicans responded by doing the same to their Indian enemies.

The raids and counter-raids escalated throughout the 1830s and 1840s, reducing thriving villages and settlements into ghostly “deserts,” as observers at the time called them. By the eve of the U.S. invasion, the violence spanned nine states and had claimed thousands of Mexican and Indian lives, ruined much of northern Mexico’s economy, stalled its demographic growth, depopulated its vast countryside and turned Mexicans at nearly every level of government against each other in a struggle for scarce resources. This sprawling, brutal conflict — what I call the War of a Thousand Deserts — had profound implications not only for the northern third of Mexico but also for how Mexicans and Americans came to view one another prior to 1846, for how the U.S.–Mexican War would play out on the ground and for the conflict’s astonishing conclusion: Mexico losing more than half its national territory to the United States. This outcome, one that continues to shape the power, prosperity and potential of Mexico and the United States today, is incomprehensible without taking non-state societies and their politics into account.

And yet, at the time, few Mexicans or Americans saw Indians as important actors. By the 1830s, observers north and south of the Rio Grande agreed that while tribes could be troublesome to nation-states, they were no longer entities of national, let alone international, significance. The trouble was that northern Mexico’s worsening situation was indeed a matter of mounting national and international concern. Anglo-Americans and Mexicans overcame this interpretive problem by adjusting their gaze and looking through Indians rather than at them. They came to use Indian raiders as lenses calibrated to reveal essential information about one another. Rather than take native polities seriously, Anglo-Americans used Indians to craft useful caricatures of Mexicans, and Mexicans used Indians to do the same with Americans.

To understand how this was done, listen to Stephen F. Austin, the “founding father” of Anglo-Texas. When American colonists in Texas revolted against Mexican rule in 1835, they dispatched Austin to tour the United States in order to capitalize on sympathy for the movement. Austin delivered a stump speech in several cities, laying out the Texan case. “But a few years back,” he began, “Texas was a wilderness, the home of the uncivilized and wandering Comanche and other tribes of Indians, who waged a constant warfare against the Spanish settlements… . The incursions of the Indians also extended beyond the [Rio Grande], and desolated that part of the country. In order to restrain the savages and bring them into subjection, the government opened Texas for settlement…. American enterprise accepted the invitation and promptly responded to the call.”

This story, which we can call the Texas Creation Myth, would be repeated in scores of books, memoirs and speeches and was chanted like a mantra by ambassadors from Texas to the United States. The myth maintained that: (a) Texas had been a wasteland prior to Anglo-American colonization; (b) Americans had been invited to Texas in order to save Mexicans from Indians; and (c) the Americans did so. As one author put it, “the untiring perseverance of the colonists triumphed over all natural obstacles, expelled the savages by whom the country was infested, reduced the forest to cultivation, and made the desert smile.”

In Washington, friends of Texas enthusiastically rehashed these arguments in the U.S. Congress. Sympathetic senators insisted that Americans had been “invited to settle the wilderness, and defend the Mexicans against the then frequent incursions of a savage foe.” Counterparts in the House explained that Mexicans had used the colonists as “a barrier against the Camanches [sic] and the Indians of Red River, to protect the inhabitants of the interior States,” and that thanks to the hardy Anglo-American pioneers, “[t]he savage roamed no longer in hostile array over the plains of Texas.”

The Texas Creation Myth introduced a set of ideas about Indians and Mexicans into American political discourse at a moment when the nation was taking notice of the whole of northern Mexico for the first time. In the decade after the Texas rebellion, American newspaper accounts, diplomatic reports, congressional documents, memoirs, travel accounts and regional histories detailed brutal, devastating raiding campaigns afflicting a huge proportion of Mexico’s territory, from New Mexico south to the state of San Luis Potosí. Geographically minded readers would have marveled at the distances involved. Had Comanches journeyed east from their home ranges instead of south, they would have been in striking range of Nashville or Atlanta. And, by all accounts, Mexican ranchers, militia, even regular military personal could do little to stop the killings, theft, destruction and kidnappings that attended the far-flung campaigns. In 1844, for example, the important publication Niles’ National Register reported that Comanches had killed one fourth of General Mariano Arista’s entire northern army in a single engagement.

The Texas Creation Myth introduced a set of ideas about Indians and Mexicans into American political discourse at a moment when the nation was taking notice of the whole of northern Mexico for the first time. In the decade after the Texas rebellion, American newspaper accounts, diplomatic reports, congressional documents, memoirs, travel accounts and regional histories detailed brutal, devastating raiding campaigns afflicting a huge proportion of Mexico’s territory, from New Mexico south to the state of San Luis Potosí. Geographically minded readers would have marveled at the distances involved. Had Comanches journeyed east from their home ranges instead of south, they would have been in striking range of Nashville or Atlanta. And, by all accounts, Mexican ranchers, militia, even regular military personal could do little to stop the killings, theft, destruction and kidnappings that attended the far-flung campaigns. In 1844, for example, the important publication Niles’ National Register reported that Comanches had killed one fourth of General Mariano Arista’s entire northern army in a single engagement.

When Comanches had to face Americans, in contrast, they appeared “timid and cowardly.” So it was, another author insisted, that Comanches chose to attack Mexicans, a degraded, mongrel people, “an enemy more cowardly than themselves, and who has been long accustomed to permit them to ravage the country with impunity.” Here then, as in talk about Texas, American discourse about northern Mexico made Indians into the great signifiers of, rather than the reasons for, Mexico’s failures. Like Texas prior to colonization, northern Mexico was in tatters not because Indians were strong but because Mexicans were weak. And, as with the Texas Creation Myth, stories about Indian raids from across the north rhetorically invalidated Mexico’s claim to the land, only on a much larger scale.

Meanwhile, Mexicans themselves talked urgently about Indian raiding in the 1830s and 1840s. Their conversation was marked above all by division between northerners and national leaders in the center of the Republic. Northern editors, community groups and officials frequently styled raiders as psychotic animals killing just to kill. Nonetheless, they insisted that los salvajes posed a national threat and implored their superiors in Mexico City for help fighting the “eminently national war” against them. Mexico’s leaders thought northern rhetoric backward and sensationalistic; they often took a more paternalistic view and looked forward to the day when Apaches and Comanches would become Catholic, civilized Mexicans. Distracted by rebellions, budgetary and economic crises, coups and skirmishes with foreign powers, national leaders more or less ignored Indian raiding, treating it more like localized crime than a national war. “Indians don’t unmake presidents,” as one defense minister candidly put it.

Despite their differences, northerners and national officials had something in common with each other and with observers in the United States: they seemed incapable of taking independent Indians seriously as coherent political communities. Indian raiders were either disorganized, bloodthirsty predators or pitiful, wayward children. To maintain these views, Mexicans had to ignore masses of evidence that Indians were able to organize themselves to an astonishing degree in the pursuit of shared goals.

So Mexicans found themselves in a conceptual bind. But there was a way out. By the early 1840s, northern commentators began suggesting that Texans, and even Americans, might somehow be behind Indian raids. This idea developed unevenly at first, but then two things happened in 1844 that gave it irresistible explanatory power both in the North and in Mexico City. First, in the spring of that year, the Tyler administration in Washington asked the Senate to approve a treaty for the annexation of Texas. Low-level and mostly indirect tension with the United States suddenly became intense and direct. Second, after a relatively quiet 1843, the entire North experienced a huge expansion in the scope and violence of Indian raiding. The timing and severity of these attacks fueled speculation that Americans were involved, and small but significant details deepened these suspicions. In October 1844, for example, in the aftermath of a bloody battle with Comanches, Mexican forces discovered that some of the dead raiders had U.S. presidential peace medals around their necks. Other encounters elsewhere in the North also seemed to confirm the link.

It appeared that Indian raiding suddenly had, in the words of a northern editor, “more advanced objectives than killing and robbing.” More and more Mexicans subscribed to the idea of a conspiracy between Americans and Indians as international tensions increased. Soon after James K. Polk assumed the presidency in early 1845, no less a figure than Mexico’s minister of war confidently explained to the Mexican Congress that the “hordes of barbarians” were “sent out every time by the usurpers of our territory, in order to desolate the terrain they desire to occupy without risk and without honor.” The minister described an agreement whereby the U.S. provided Indians not only with arms and ammunition but with a political education, with “the necessary instruction they need to understand the power they can wield when united in great masses… .” In fact, American provocateurs had little or nothing to do with native policy. However Comanches obtained the peace medals (if in fact the report was accurate), their leaders had slender connection to American officials and needed no encouragement to raid Mexicans. Still, the claim didn’t have to be true to be useful. Mexico had escaped its conceptual bind by looking through Apaches, Navajos and Comanches and seeing Americans on the other side. Mexicans were at last constructing a single national discourse on raiding that could secure unity against Indians and norteamericanos alike.

But the consensus came too late. Once in power, President Polk tried to pressure Mexico into selling its vast northern territories. When that failed, he ordered General Zachary Taylor to march south of the Nueces River, into territory Mexico considered its own, in hopes that he would either compel a sale or precipitate a land war. He failed in the former but accomplished the latter. In the summer of 1846, Taylor provoked a Mexican reaction and started a war.

But the consensus came too late. Once in power, President Polk tried to pressure Mexico into selling its vast northern territories. When that failed, he ordered General Zachary Taylor to march south of the Nueces River, into territory Mexico considered its own, in hopes that he would either compel a sale or precipitate a land war. He failed in the former but accomplished the latter. In the summer of 1846, Taylor provoked a Mexican reaction and started a war.

The War of a Thousand Deserts influenced the U.S.–Mexican War in two critical ways. First, it facilitated the U.S. conquest and occupation of the Mexican North and, by extension, helped make possible the decisive campaign into central Mexico. As they marched throughout northern Mexico, U.S. troops moved through a shattered, ghostly landscape, literally marching in the footsteps of Apaches and Comanches, to defeat an enemy that had already endured 15 years of war and terror. American officers had a message for these beleaguered people, provided in advance by Polk and the War Department. “It is our wish to see you liberated from despots,” General Taylor was to announce, “to drive back the savage Cumanches [sic], to prevent the renewal of their assaults, and to compel them to restore to you from captivity your long lost wives and children.”

Northerners desperately needed help, because Apaches, Navajos and especially Comanches and Kiowas intensified their raiding activities during the U.S.–Mexican War. The destructive history and ongoing, even worsening reality of raiding seriously compromised northern Mexico’s contribution to the war effort. For the most part, Mexican military officials simply exempted northern communities from the draft because of ongoing Indian raids. When Mexico City did ask northerners for help, they rarely got it. In 1847, for example, when General Antonio López de Santa Anna was raising an army to confront Zachary Taylor, he planned on drawing about a fifth of his troops from the states of Chihuahua, Durango and Zacatecas. All three states were coping with Apache and Comanche raiders, and all three refused to send Santa Anna any men. In February of that year, in his best chance to reverse the dynamic of the war, Santa Anna lost the Battle of Buena Vista by the narrowest of margins.

Just as importantly, raids discouraged northern Mexicans from leaving their families and joining insurgents fighting the American occupation. A knowledgeable observer estimated that northern Mexico should have been able to produce 100,000 men to wage irregular warfare against American troops. Such an insurgency could have made the American occupation unworkable as well as making the later campaign into central Mexico a practical and political impossibility. But no such insurgency materialized. General José Urrea, a key northern guerrilla leader, attracted fewer than a thousand men, and his movement never became more than a nuisance to the occupation. Impoverished and embittered by Indian raiding, northern men understandably felt reluctant to leave their families and property undefended against Indians in order to help a government that had done so little to help them.

The second way that the War of a Thousand Deserts shaped the U.S.–Mexican War was that it allowed American leaders to style the dismemberment of Mexico as an act of salvation. By the time senators began talking seriously about how much territory to demand from Mexico, expansionists could draw on more than a decade of observations to describe a Mexican North empty of meaningful Mexican history and, by all appearances, increasingly empty of Mexicans themselves. “The Mexican people [are] now receding before the Indian,” a Virginian senator observed, “and this affords a new argument in favor of our occupation of the territory, which would otherwise fall into the occupation of the savage.” The crucial twin to this idea was that Americans would do what Mexicans could not: defeat the Indians and make the vast desert that was northern Mexico smile with improvement and industry. President Polk himself made this case before Congress in 1847, when he defended the notion of annexing more than a million acres of Mexican territory. The cession would improve life for Mexicans north of the line, Polk insisted, but, more importantly, “it would be a blessing to all the northern states to have their citizens protected against [the Indians] by the power of the United States. At this moment many Mexicans, principally females and children, are in captivity among them,” the president continued. “If New Mexico were held and governed by the United States, we could effectually prevent these tribes from committing such outrages, and compel them to release these captives, and restore them to their families and friends.” One might dismiss this as tiresome, insincere rhetoric, but I think Polk believed what he said about Mexico’s plight and his nation’s ability to end it, and that most of his audience in Congress believed these things, too. Indeed, Article 11 of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the war, solemnly bound U.S. authorities both to restrain Indians residing north of the new border from conducting raids in Mexico and to rescue Mexican captives held by Indians.

The second way that the War of a Thousand Deserts shaped the U.S.–Mexican War was that it allowed American leaders to style the dismemberment of Mexico as an act of salvation. By the time senators began talking seriously about how much territory to demand from Mexico, expansionists could draw on more than a decade of observations to describe a Mexican North empty of meaningful Mexican history and, by all appearances, increasingly empty of Mexicans themselves. “The Mexican people [are] now receding before the Indian,” a Virginian senator observed, “and this affords a new argument in favor of our occupation of the territory, which would otherwise fall into the occupation of the savage.” The crucial twin to this idea was that Americans would do what Mexicans could not: defeat the Indians and make the vast desert that was northern Mexico smile with improvement and industry. President Polk himself made this case before Congress in 1847, when he defended the notion of annexing more than a million acres of Mexican territory. The cession would improve life for Mexicans north of the line, Polk insisted, but, more importantly, “it would be a blessing to all the northern states to have their citizens protected against [the Indians] by the power of the United States. At this moment many Mexicans, principally females and children, are in captivity among them,” the president continued. “If New Mexico were held and governed by the United States, we could effectually prevent these tribes from committing such outrages, and compel them to release these captives, and restore them to their families and friends.” One might dismiss this as tiresome, insincere rhetoric, but I think Polk believed what he said about Mexico’s plight and his nation’s ability to end it, and that most of his audience in Congress believed these things, too. Indeed, Article 11 of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the war, solemnly bound U.S. authorities both to restrain Indians residing north of the new border from conducting raids in Mexico and to rescue Mexican captives held by Indians.

As it turned out, however, the United States found it much harder than expected to control the independent Indians in their newly acquired territory. Cross-border raiding actually surged after the war, peaking in the mid-1850s. Raids would, in fact, continue in diminished form for decades, at least until the surrender of Geronimo and his Chiricahua Apaches in 1886. But despairing of its ability to honor the terms of the treaty and threatened with massive lawsuits from the Mexican landholders who had lost so much to raiding after 1848, the United States bought its way out of Article 11 in 1854 as part of the Gadsden Purchase.

In the years and decades following that little humiliation, historians on both sides of the border stuck to the longstanding notion that Indians were at best bit-players in the geopolitics of the U.S.–Mexican War — significant maybe as symptoms of Mexican weakness or American treachery but generally irrelevant in their own right. With stories about non-state actors crowding our newspapers, blogs and talk shows these days, perhaps it is time to revisit the U.S.–Mexican War and to acknowledge the centrality of stateless Indian peoples to that conflict and its manifold long-term consequences.

Brian DeLay is an associate professor of History at UC Berkeley. He gave a talk for CLAS on September 20, 2010.