“The sewer is the conscience of the city.”

–Victor Hugo, “Les Miserables”

If Mexico City’s sewer reflects its conscience, then citizens of the mega-metropolis have little ground for pride. The award-winning documentary “H2Omx” uses powerful imagery to tell the story of Mexico City’s fraught water system. Green pipes snaking through the nation’s capital and delivering water to millions of people but failing to reach those living in impoverished localities. Post-apocalyptic scenes of trash clogging major river systems and toxic foam from chemical detergents floating through the air like snow, silently poisoning entire communities. Thousands of acres of land irrigated with aguas negras — black waters flowing from Mexico City’s sewers — destined to crops for human consumption. “H2Omx” depicts natural resource destruction on a scale so large that it threatens not only the livelihoods of millions of people, but also the identity of the city itself.

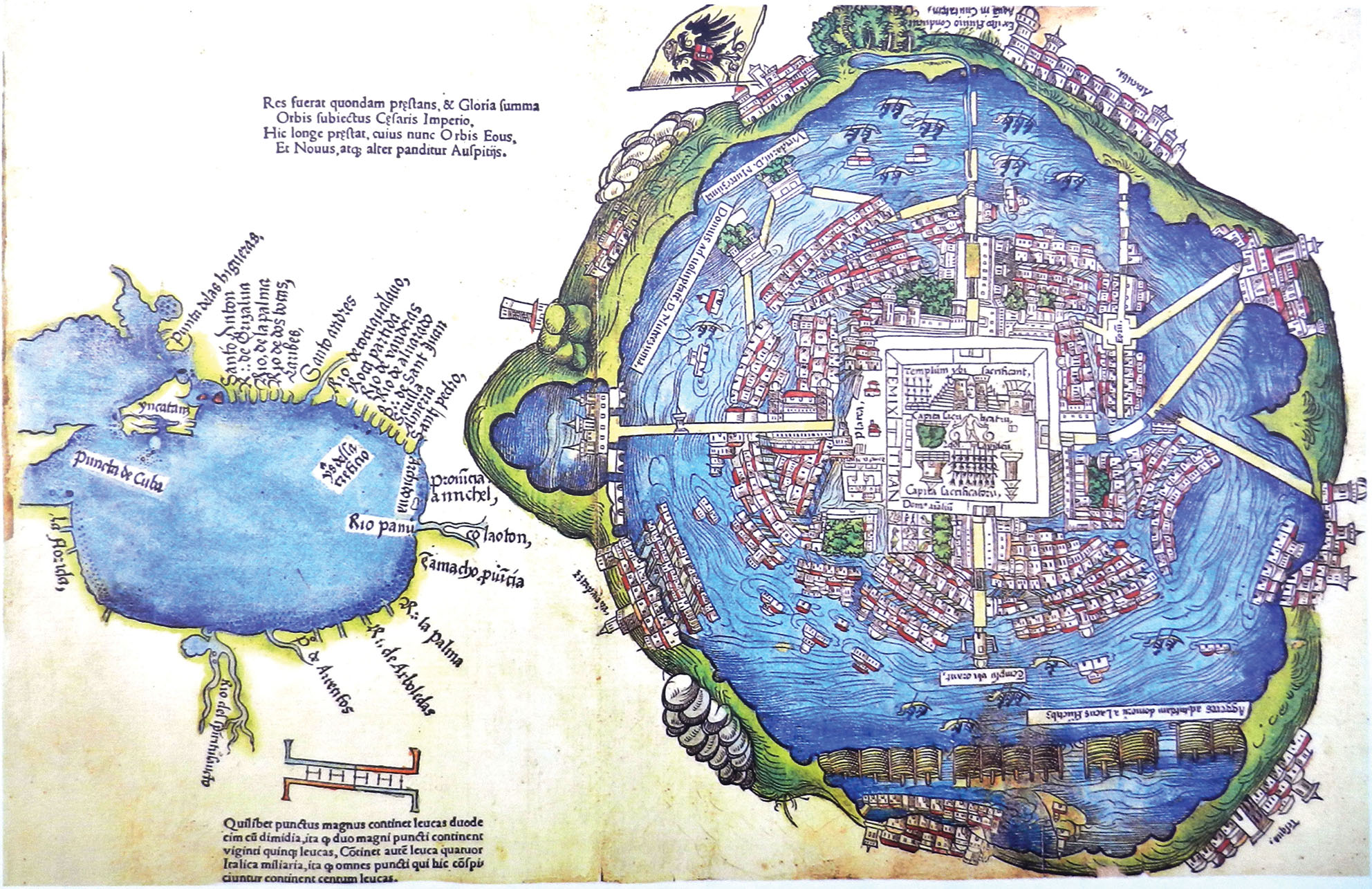

Built over a lake, Mexico City “should not even be there,” we are told. When the Spanish arrived to what was then Tenochtitlán, they found a vibrant city built on an island in a large lake, which was linked to the mainland through four causeways. The Spanish decided to continue developing the capital of their new colony in the same location, ultimately by draining the lake but without taking precautions to manage the water as the Aztecs had done for nearly two centuries. Slowly, canals were turned into streets, and rivers became part of the city’s sewer system.

Building a city atop a lakebed may seem like a recipe for disaster, and it is. Especially when that city exploits its underground water reservoirs. In this regard, centuries of over-pumping have led to the sinking of the downtown area — which sits 10 meters lower than when it was built. This sinking, in conjunction with the geography of the city (which does not have natural exits for water inflows), significantly increases susceptibility to flooding. Despite billions of dollars invested in infrastructure, the city floods every year, taking a major toll on econo-mic activity, damaging property, and causing substantial public health problems. Despite frequent downpours, only 8 percent of annual rainfall recharges underground reservoirs, leading scientists to predict that this dangerous imbalance will likely leave the city dry in only eight to ten years.

In response to scarcity, a large proportion of the water consumed in Mexico City is imported from other states though the massive Cutzamala System. The water in the system flows through seven dams and hundreds of miles of pipes, tunnels, and open canals, providing short-term relief to Mexico City’s underground reservoirs but leaving communities outside the city without water. Imports, moreover, are not nearly enough to cover demand, and 40 percent of the water imported from outside the city is lost through leaky pipes.

In response to scarcity, a large proportion of the water consumed in Mexico City is imported from other states though the massive Cutzamala System. The water in the system flows through seven dams and hundreds of miles of pipes, tunnels, and open canals, providing short-term relief to Mexico City’s underground reservoirs but leaving communities outside the city without water. Imports, moreover, are not nearly enough to cover demand, and 40 percent of the water imported from outside the city is lost through leaky pipes.

“H2Omx” makes it painfully clear through individual stories that thousands of families in Mexico City’s marginal communities still have no access to water. People from these communities are forced to walk long distances to find enough of this vital resource to satisfy their most basic needs. Nonetheless, the movie pushes viewers to see these forgotten populations as areas of opportunity. For example, a project called Isla Urbana has developed a simple technology to gather rainwater from rooftops, which can provide enough water to satisfy the needs of small communities for months.

A final point raised by the film is the discharge of contaminated water. “H2Omx” explains that only 7 percent of sewage water is treated, while the rest leaves the metropolis full of dangerous contaminants. Farmers in the Mexican state of Hidalgo then use this water to grow grains and vegetables that are sent back to Mexico City to fill the plates of urban diners in what farmers call a form of “just revenge.”

After the screening of “H2Omx,” UC Berkeley professors Ivonne del Valle and Isha Ray discussed their impressions of the film. Isha Ray, also Co-Director of the Berkeley Water Center, mentioned that the central issue of the movie is inequality, because not all citizens experience the impacts of a failing water system. Whereas millions of Mexicans have access to clean water in their homes every day, millions more have barely enough to drink, let alone to wash and cook. Others live alongside a massive canal carrying aguas negras and experience negative health impacts because of it.

Ray also noted the profound connection between food and water. It is common in metropolitan areas for sewage water to be sent to farms and used to irrigate produce that is then trucked back into the city to feed its citizens. However, the people who are really suffering from this arrangement are not the unsuspecting diners in the city, but rather the farmers who work in fields where levels of heavy metals are off the charts. These agricultural workers are experiencing cancer and infectious diseases at higher and deadlier rates than the people in the city who are becoming temporarily ill from eating contaminated produce.

Ivonne del Valle, who specializes in Colonial Mexico, explained that Mexico City’s water troubles date back to Hernán Cortés, who decided he wanted to build a city on a lake, despite the best efforts of his men to warn him against it. She also mentioned that the first war between the Spaniards and the indigenous groups of the Valley of Mexico was over water. She compared historical battles over resources to the war that rages on today between humans and nature.

Professor del Valle also emphasized her disagreement with the law currently under discussion in the Mexican Congress, the “Nueva Ley General de Aguas” (New General Water Law), which essentially privatizes water in the country. The main problem with this law is that it would encourage industrial waste and fracking practices, which are not properly regulated. Del Valle also mentioned that the student group “Agua Para Todos” (Water for Everyone) is fighting against the new law.

The event was not all doom and gloom, however. A final point made during the question and answer session raised potential solutions to Mexico’s water woes. Isha Ray explained that despite difficulties with financing, decentralized solutions such as water treatment plants and rainwater harvesting projects do work to improve health and well-being of communities in Mexico and other parts of the world. However, Ray warned that to adequately address challenges as great as those faced by Mexico City, radical policy change is needed. Through its stunning and occasionally heart-breaking visuals and lively narrative flow, “H2Omx” acts as a powerful catalyst for change in Mexico City’s water system and beyond.

Isha Ray is Associate Professor with the Energy and Resources Group and Co-Director of the Berkeley Water Center at UC Berkeley. Ivonne del Valle is Associate Professor at UC Berkeley’s Department of Spanish & Portuguese. They spoke for CLAS on April 9, 2015, following a showing of the documentary “H2Omx,” winner of the 2014 Margaret Mead Filmmaker Award.

Femke Oldham and Ignacio Camacho both hold Master of Public Policy degrees from the Goldman School of Public Policy at UC Berkeley.