A grainy video implicates Baja California’s State Attorney General of trying to take control of organized crime in Mexicali with the help of the Sinaloa Cartel, one of the most powerful and violent drug trafficking organizations in Mexico. In the video, a man who claimed to run the Mexicali cell of the cartel said that his team was asked to kill policemen who were stealing merchandise. The man in the video was tortured, killed, and left in a car in front of the house of the Attorney General’s girlfriend.

This video was delivered to several news outlets in Baja California, but only Zeta, a Tijuana-based weekly, uploaded it and investigated the allegations. After publishing the story, journalists at Zeta saw that nothing happened: the Attorney General stayed on the job and faced no consequences.

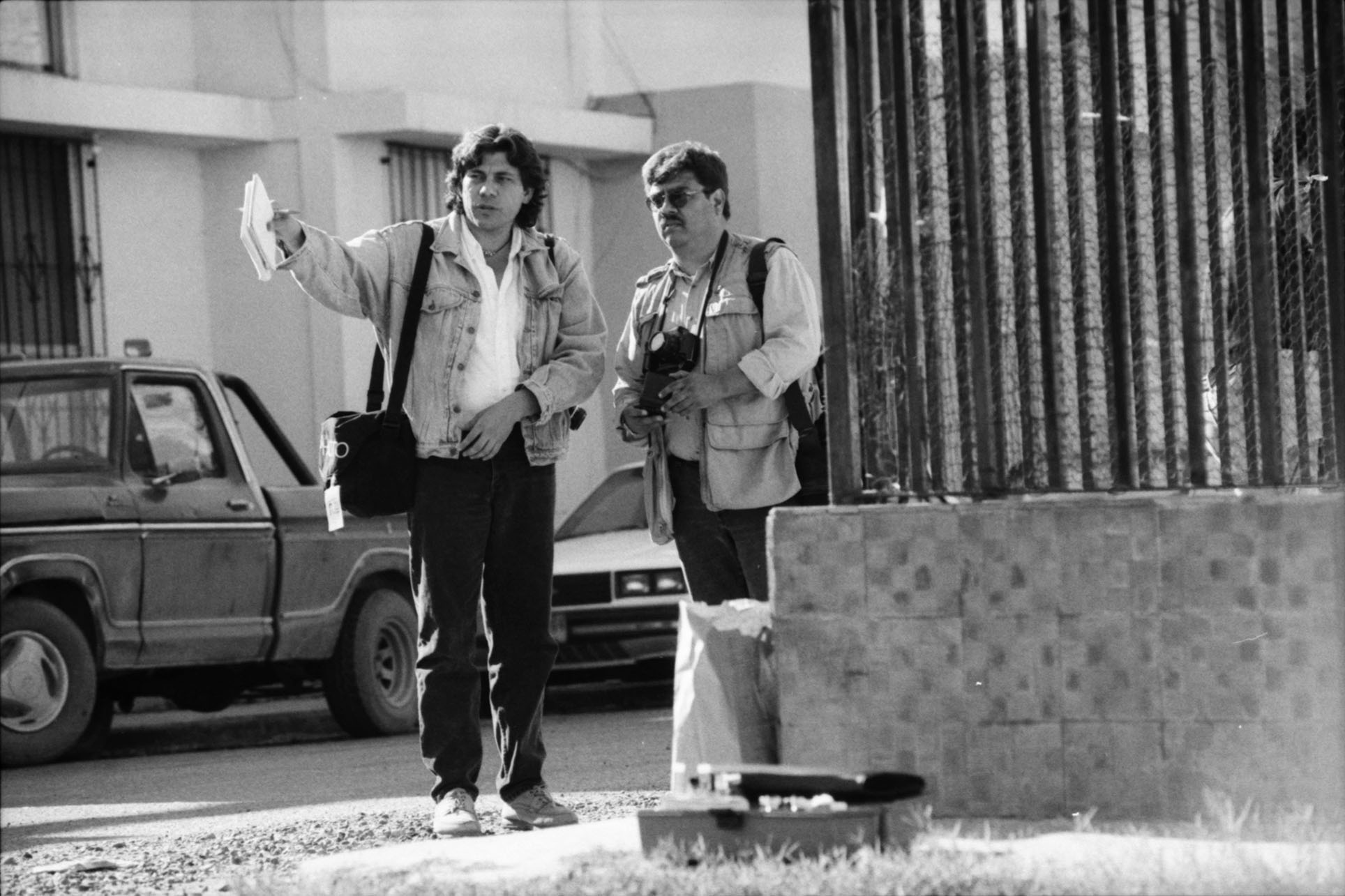

Bernardo Ruiz’s 2012 documentary, “Reportero,” recounts the history of Zeta, from its foundation in 1980 to the assassination of several of its journalists by organized crime. The story is told through Sergio Haro, a serious photojournalist who is so dedicated to his job that he has continued to work, even after receiving death threats from drug cartels.

Told primarily through archival video footage of known cartel members, photos of Zeta’s founders, and video interviews, the film pulls back and shows that the violence faced by journalists in Mexico began before President Felipe Calderón’s drug war.

Over time, the physical and psychological toll of this conflict has shredded journalists’ ability to report. Since January 2007, more than 42 members of the press have been murdered, and several have disappeared. Because they were fearful of retaliation, the other news outlets that also received the video confession implicating the Attorney General did not pursue the story. Only Zeta.

To safeguard the individual journalists, explosive stories that might elicit threats are published under an anonymous byline: Investigaciones Zeta. Taking advantage of its proximity to the United States, Zeta prints its paper on the California side of the border. But for a small regional paper, anonymous bylines and printing outside of Mexico can only offer so much protection.

In the talk that he gave as part of the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism’s Unity Film Series — an event organized by the student chapter of the National Association of Hispanic Journalists and CLAS — Ruiz stated that, while he and his crew never felt like they were in direct danger during the two-year production, Zeta’s editor-in-chief, Adela Navarro, did receive threats while filming “Reportero.” Ruiz explained that the threats did not stem from her participation in the film, but from Navarro’s “ongoing reporting that looked at the nexus between political corruption and the narcos.”

In the film, Adela Navarro said that in Mexico, criminals have impunity. Zeta publishes the names of corrupt politicians, investigates the murders of their own journalists, and does not shy away from drug-trafficking stories, yet criminals are rarely arrested or prosecuted. “They can kill whomever they want,” Navarro said.

This fact weighs on the Zeta staff. They are constantly reminded of the assassination of co-founder Francisco Ortiz Franco and columnist Héctor Félix Miranda as well as the assassination attempt against co-founder and former editor-in-chief Jesús Blancornelas.

“We can now publish what we want, but we also suffer the consequences,” Navarro said.

Despite the dangers inherent to the job, photographer Haro continues to report, tracking down the stories. He’s in constant movement: always driving, winding down desert roads, through traffic-jammed Tijuana streets, and at night, when the red and green lights illuminate the car, he remembers the deaths of journalists he worked with.

Haro struggles to tell stories about social issues, but like other residents of Tijuana, he is constantly pulled into the world of corrupt politicians and organized crime.

With a camera around his neck at all times, Haro takes portraits of people picking through garbage dumps and youths in a shelter who have just been deported from the United States. Ruiz then frames each subject in an intimate video portrait. The older men picking through trash quietly stare at the camera. A teenage boy with dark hair looks into the lens, hesitant. These shots are the film’s strongest and most memorable moments. Removed from interview voice-overs about corrupt officials and assassinated journalists, these are the faces of regular people who are affected by drug violence. These are the people who do not know what their next meal is going to be and kids who have no job prospects but might consider working for the lucrative drug trade.

With a camera around his neck at all times, Haro takes portraits of people picking through garbage dumps and youths in a shelter who have just been deported from the United States. Ruiz then frames each subject in an intimate video portrait. The older men picking through trash quietly stare at the camera. A teenage boy with dark hair looks into the lens, hesitant. These shots are the film’s strongest and most memorable moments. Removed from interview voice-overs about corrupt officials and assassinated journalists, these are the faces of regular people who are affected by drug violence. These are the people who do not know what their next meal is going to be and kids who have no job prospects but might consider working for the lucrative drug trade.

Through these personal stories, Ruiz found the subject of his film. While doing research at a shelter for deported minors, Ruiz heard stories from everyone about kidnappings and extorted business. After meeting Haro in the course of this work, Ruiz “knew it would be more urgent” to do a film about Haro and Zeta.

“I and many others would argue that there is a very serious human rights crisis in Mexico,” Ruiz said.

In the last several months, Mexico has received growing international attention, primarily with the disappearance of the 43 students in Ayotzinapa. “It was the state,” protesters shouted in the streets, revealing the profound distrust citizens feel towards city, state and federal officials.

Ruiz recalls a conversation he had with Haro while filming in which the Zeta journalist explained that, despite the threats surrounding his job, he does not consider himself an activist. His responsibility as a reporter was just to get the information out there; it was up to the judiciary and civil society to do something with that information. And now, as the protest movement continues to grow, it seems like Mexico is at a tipping point. Ruiz believes that the missing students have galvanized civil society. “There’s a broader human rights context with which we have to look to the press,” Ruiz said.

The death of journalists is an issue that’s now part of the civil movement in Mexico. In the wake of incidents like the firing of Carmen Aristegui, one of Mexico’s most prominent journalists, the country is mobilizing. But reporters at small regional news outlets remain vulnerable. Unlike Zeta, other papers cannot protect their press freedom by printing in the United States.

And the drug trade is a growth industry. Media outlets that cover violent gun battles and other narco news sell papers. Auto body shops that specialize in bulletproof windows and chassis have had business grow exponentially since the start of the conflict. At one point in the film, the owner of a shop that actually advertises in Zeta goes over the different plans available for customers, who range from those who only want to feel more protected to those who are expecting to be shot any day now. The cost of the armored vehicle also varies depending on whether customers are looking to stop handguns, assault rifles or machine guns.

Corruption runs so deep that after Haro’s life is threatened, the documentary delivers one of its more poignant moments. As the camera focuses on him in his truck, with his wife and son in the rear seat as the background, Haro explains that he has received a death threat. The State Attorney General sent 20 state guards to protect him, but after spending some time with them, Haro decides to strike out on his own. “They justify their corruption,” Haro said, “I’d rather take care of myself.”

During the two-year production of “Reportero,” Ruiz and his crew witnessed how Zeta leverages its position in a border city to protect itself. They are independent and aggressive — a bit sensationalistic for some readers — but their will for strong reporting never falters. New, younger journalists continue to join their ranks, learning from Haro, Navarro, and other journalists who have been reporting for decades.

The death of a journalist is rarely investigated, corrupt officials never leave office, and people continue to be murdered by cartels. But now, the people of Mexico have taken to the streets to protest corruption and violence and to support freedom of the press.

“I think the question remains, what kind of support do they have from the international community,” Ruiz concluded.

Bernardo Ruiz is an independent filmmaker based in New York. On March 30, he spoke at the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism’s Unity Film Series event organized by the student chapter of the National Association of Hispanic Journalists and CLAS.

Yolanda Martinez is a multimedia student at the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism.