How do academics choose what they study? Many of my political-science colleagues will offer professional answers: what they work on is “at the core of the scholarly debate in the field,” or alternatively, the subject has been “undertheorized” and there is a “gap in the literature”; or they will give the increasingly common response, “there is a great data set to work with.” Usually that’s where the conversation stops. Push a little more, though, and some will confess that the initial spark of interest may have been more personal — a particular life experience or event that left a lasting impression. But for the most part, professors strain to depersonalize what they do, maintaining the veneer of professional detachment and scholarly objectivity.

For most of my career, I carefully followed that academic script. When asked why I study border policing, I would dryly reply that it provides analytical insight into how states cope with the stresses and strains of territorial control in an increasingly globalized world; or when asked why I’m interested in cross-border smuggling, I’d reply that the illicit side of globalization receives too little attention from international-relations scholars despite its growing importance. Those sorts of safe answers helped me get funded to do dissertation fieldwork on the U.S.–Mexico border, secure a good job at a research university, win grants and fellowships, and ultimately, get tenure.

The answers were truthful, but they conveniently obscured as much as they revealed — so much so that I myself didn’t dwell much on the deeper, personal truth, which I perhaps subconsciously feared might make me professionally suspect.

My childhood was defined by a chaotic life of clandestine border crossings. My mother, a traditional 1950s Mennonite housewife who became a ’60s radical feminist and Marxist revolutionary, abducted me when I was a young boy during a bitter custody battle with my father. We fled across state lines and national borders, constantly moving and hiding. Between the ages of five and eleven, I attended more than a dozen schools and lived in more than a dozen homes, moving from the comfortably bland suburbs of Detroit to a hippie commune in Berkeley to a socialist collective farm in Chile to highland villages and coastal shantytowns in Peru.

In October 1973, a month after the military coup that over threw Chile’s socialist president, Salvador Allende, my mother turned me into a smuggler as we fled the country. We were crossing from Chile to Argentina through the high Andes by bus, headed for Buenos Aires from Santiago. At a remote mountain border checkpoint, we had to get off the bus to be searched by Chilean soldiers. As we watched them frisk passengers ahead of us, sift through luggage, and check documents, my mother and I grew increasingly nervous. Tucked inside the cover of one of my notebooks, buried under my clothes, was a small poster depicting a crowd of farmworkers with raised pitchforks, sticks, banners, and clenched fists. It said, CONSEJOS COMUNALES: UNIDAD Y PARTICIPACION CAMPESINAS. The consejos (councils) were becoming organs of political power only in the final days of the Allende government. Gambling that the soldiers would overlook the innocent-looking eight-year-old gringo at her side, my mother had hidden this poster in my belongings, determined to smuggle this political memento out of the country as a last little act of defiance.

I did my best not to look nervous. While the soldiers patted my mother down and rifled through her luggage, I held my breath, avoided eye contact, and stared at my feet. They simply waved me through. I had no idea what they would have done if they had caught me, maybe just confiscate the poster, but I was glad to not find out.

Later, my mother used me to help her smuggle large wads of cash into Mexico as we headed south to evade an arrest warrant for my kidnapping. She had sewn extra pockets inside our pants to hide the money and keep it safe. As we walked across the border bridge from El Paso into Juárez, I was flattered by my mother’s trust in me, but the bulky pile of crisp $100 bills in my pants, poking out around my waist, made me self-conscious. Could the Mexican border guards standing lazily to the side as we went through the metal gate tell I was moving awkwardly? Fortunately, there was no inspection of any sort going into Mexico.

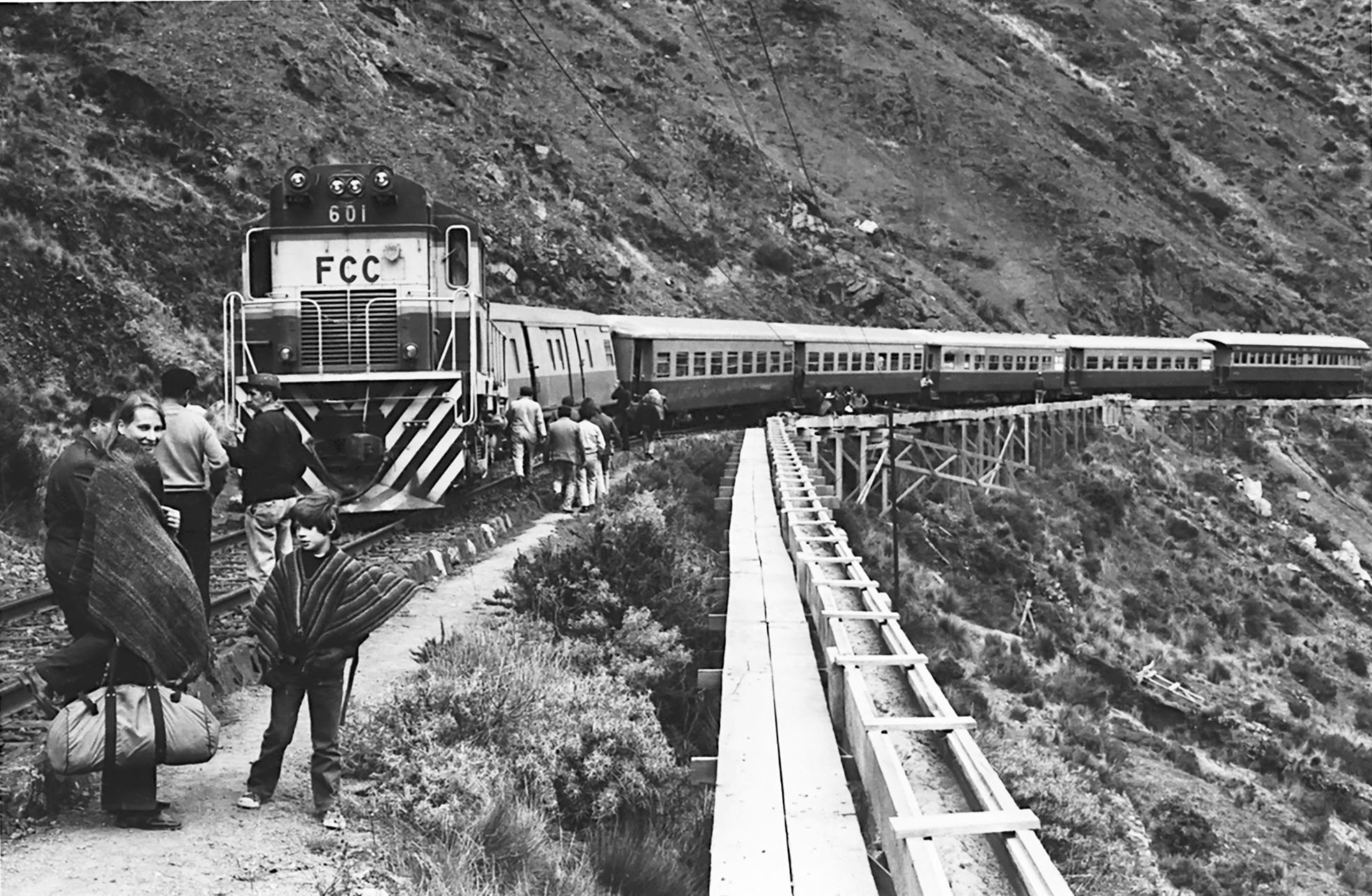

More than a decade later, right after graduating from college, I bummed around Colombia, Peru, and Bolivia for four months with my girlfriend. During that trip, I became a smuggler’s accomplice. As we crossed from Peru into Bolivia, a friendly old lady sheepishly asked me to store a bag full of toilet paper under my seat. I didn’t understand until the border guards began confiscating smuggled toilet paper from the passengers. The toilet-paper demand came from the Bolivian cocaine industry, where it was commonly used to dry and filter coca paste that was then transported to remote jungle laboratories to be refined into powder cocaine. Most of that would eventually end up in the noses of American consumers.

A few weeks later, we caught a ride on a cargo boat traveling down the Amazon River from Iquitos, Peru, to Leticia, Colombia, a bustling jungle town at the convergence of Peru, Colombia, and Brazil, which owed much of its existence to smuggling. Late at night before our departure, I watched as several dozen drums of chemicals were quietly loaded onto our boat; they were offloaded in the middle of nowhere before we reached Leticia.

I would later find out that many of the chemicals used by the Andean cocaine industry were actually imported from the United States and ended up on the black market. America’s rapidly escalating “war on drugs” was so focused on stopping the northward flow of cocaine that it had largely overlooked the equally important southbound flow of U.S. chemicals needed to cook the coke. I ended up writing a short article about it for The New Republic, which led to an invitation to testify before a Senate hearing on chemical diversion and trafficking — with industry lobbyists sitting nervously in the audience. I was hooked on trying to figure out the business of drugs and the politics of drug control.

Though I’ve always told myself that this post-college episode was the starting point of my professional interests, it’s possible those roots are deeper. I did not give that much thought until after my mother’s death. I found scattered through her tiny red-brick house more than a hundred dusty old diaries. They covered three decades, beginning in the years when she and I had traveled South America together. I had often watched my mother write in her diaries, but I had no idea she had kept them all. I spent weeks reading through them, a way of talking to my mother one last time, reliving my roller-coaster childhood by her side as we fled, time and again, across borders.

Now, many years later, these diaries have helped me to overcome my professional inhibitions enough to finally tell the story of a childhood on the run. I’ve come to realize that the personal is indeed political. In my case, I probably would not have even become a political scientist if it had not been for an intensely political childhood.

Peter Andreas holds a joint appointment at Brown University, where he is a professor of international and public affairs in the Department of Political Science and the John Hay Professor of International Studies and Political Science at the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs.

This essay draws from Andreas’s book, Rebel Mother: My Childhood Chasing the Revolution (Simon & Schuster, 2017). It originally appeared in The Chronicle Review on March 26, 2017, and is reprinted with permission.