An eight-year-old girl leans in towards the phone, chewing on the tip of a pen as her father’s voice crackles over the line.

In Spanish, he asks, “Do you know how much I want to see you?”

“How much?” She leans over the phone a little closer. There is a moment of silence.

“Like from here to where you are.”

Mexican migration to the United States most often breaks the surface of Americans’ attention in stories of migrants dying in the desert, spectacular raids on factories employing “illegals” or legislative battles over fixing the broken immigration system. The documentary “Los que se quedan” (Those Who Remain) portrays the other side of the story — the journey of waiting, absence and hope that marks the lives of those left behind in Mexico when a spouse, parent or child goes to the United States. Co-directors Juan Carlos Rulfo and Carlos Hagerman are careful to avoid explicit political statements on the usual questions that swirl around Mexican migration. Instead, with humility, grace and even humor they trace the contours of the absence created by migrants gone north and document the stark realities that force whole families into painful limbo. We do not witness the militarized U.S.–Mexican border, the rising violence of the journey north or the growing hostility toward Latino migrants in certain U.S. communities. But these specters haunt the homes and dinner tables of those left behind.

The stars of this film are the usually anonymous loved ones for whose sake so many migrants travel northwards. The stories of those who stay are colored with disappointment and longing but also with hope and strength in the face of an implacable status quo. The film delves into nine Mexican families’ everyday struggles to overcome the unique tragedy of a loved one’s migration. It offers a glimpse into the quotidian emptiness left in the wake of the countless journeys northwards. Husbands, wives, parents and children wrestle with the choice faced by so many poor families: stay together in poverty or live apart from those you love most. The film captures the blank spaces left behind and the migrants’ constant presence in their absence. The intimacy is striking, almost discomfiting, as we sit through family dinners, first-communion dress shopping, couple’s quarrels and awkward goodbyes.

By shifting the focus to those who stay, it becomes clear that they are as much a part of migration as those who make the journey. It is their presence that requires the migrant’s absence. So, we witness Yaremi, dressed in uniform, at her high school. Her father has just returned after seven years in the United States. He could not stand to be away from his wife and daughters any longer, but his homecoming may force Yaremi to abandon her education because, at home, her father cannot make enough money to pay her fees. It was to pay for his children’s schooling that he left in the first place. She can either have her father or an education and the chance of a future. As Rulfo reflected in a discussion after the film screening at the Center for Latin American Studies, documenting these realities made him savor the everyday pleasures so often taken for granted, like coming home and kissing his child good night after a long day’s work.

By shifting the focus to those who stay, it becomes clear that they are as much a part of migration as those who make the journey. It is their presence that requires the migrant’s absence. So, we witness Yaremi, dressed in uniform, at her high school. Her father has just returned after seven years in the United States. He could not stand to be away from his wife and daughters any longer, but his homecoming may force Yaremi to abandon her education because, at home, her father cannot make enough money to pay her fees. It was to pay for his children’s schooling that he left in the first place. She can either have her father or an education and the chance of a future. As Rulfo reflected in a discussion after the film screening at the Center for Latin American Studies, documenting these realities made him savor the everyday pleasures so often taken for granted, like coming home and kissing his child good night after a long day’s work.

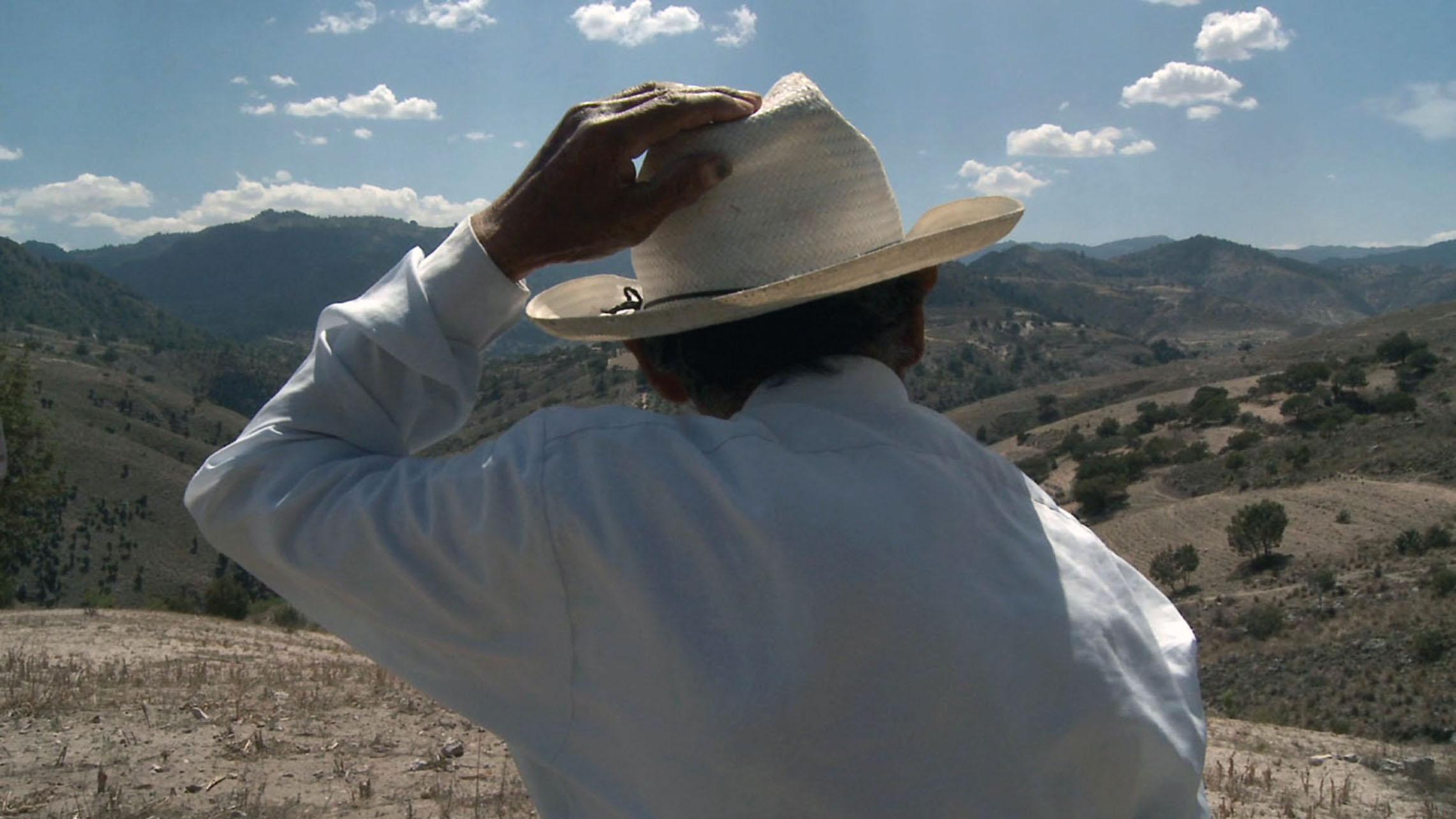

In the stories of migration and hoped-for return woven throughout the film, it becomes clear that while each family struggles and carries on uniquely, the grand narrative belongs to Mexico itself. The nine families live in six different states, and the very landscape is made to speak of the migrants’ absence and the unfulfilled dreams that drive so many north. The camera lingers on the empty doorways of unfinished homes and the dusty fields left fallow because the crops they might bear would not be worth the labor put into them. These spaces are both signs of the migrants’ absence as well as their dreams of return.

One man has been travelling back and forth to the United States for almost a decade. We see him and his wife arguing bitterly over whether he should go north again. She does not hide her cold anger at his leaving her behind again and again, returning only long enough to get her pregnant. Through most of the film, he manages to deflect her accusations and complaints, even telling the camera that all the women in his town suffer the same fate, but only the weak ones complain. But towards the end, we find him drunk and shaking his head sadly before his untilled fields. “It’s hopeless,” he mumbles. “And then they accuse you of leaving them.”

We also meet Rosi, walking through the empty rooms of the very pink house she is building with the money her husband sends home. “He’s been away for five years,” she says and smiles shyly. “When he gets back, we’ll choose who sleeps in which room.”

Clearly, the experience of those who stay is not monolithic. Don Pascual and his wife bear their three children’s nine-year absence without complaint. Don Pascual rolls a clove of garlic in his hand as he inspects the foundations of the home he is building for his son with his son’s money. They are foundations of stone he points out proudly. He says his eldest son is fed up with the United States, he is “…bored of the place. He’s going to come home.” Back in the dirt yard before a sheet metal shack, Don Pascual dusts his hat as his chickens and dogs make an ungodly racket. His wife makes tortillas on her hearth behind him. “As a mother, it breaks my heart, but we have to accept our lot in life.” Later, their two sons and daughter return. They are each at least a head taller than their parents, wearing backpacks and “American” clothes. They sit down to eat the meal that their mother has prepared for them.

For some, the absence is permanent, and they must forge new dreams and carve out new futures. Raquel, a young Maya woman, breaks down weeping before the camera as she recounts the phone call she received from the United States two years past, informing her of her husband’s murder.

Despite the hardship, the film makes clear why migration al norte will continue. For the young and the strong, staying means sacrificing the dream of a secure future. Jorge Rueda, a well-preserved man in his sixties, sits beneath a tree on his pastureland, surrounded by his cattle and horses. “My father, he went to the United States, and he told me, ‘When you grow up, you’ll go north and make money, and you’ll return home.’” He smiles enigmatically. “And what happened was that very few stayed. And those of my generation that stayed, today they have nothing.”

As “Los que se quedan” opens, small children in a schoolhouse in northern Mexico describe the treasures to be found al norte. “There is money on the ground in the U.S.” There are gifts and gold chains. And work! Their teacher asks the class who wants to go to the United States when they grow up, and the children gleefully throw up their hands. And so it seems that the next generation will also set out on the migrant’s odyssey, leaving their families to live in longing.

The Center for Latin American Studies screened the documentary “Los que se quedan” on March 8, 2011. The director, Carl Hagerman, answered questions after the film.

Anthony Fontes is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Geography at UC Berkeley.