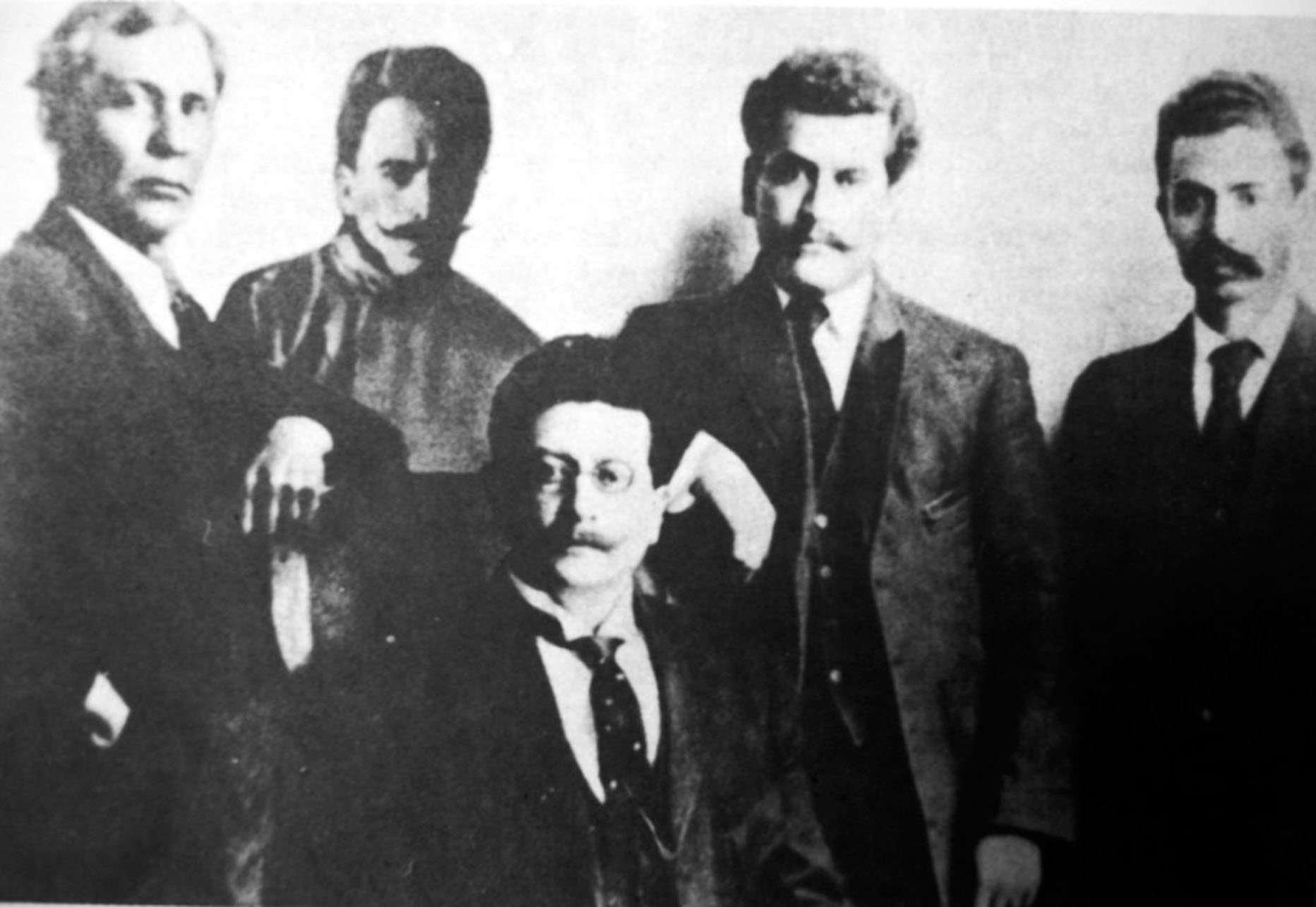

Claudio Lomnitz’s recent book, The Return of Comrade Ricardo Flores Magón, tells the story of the American and Mexican revolutionary collaborators of the Mexican anarchist Ricardo Flores Magón. The book tracks the lives of John Kenneth Turner, Ethel Duffy, Elizabeth Trowbridge, Ricardo Flores Magón, Lázaro Gutiérrez de Lara, and others involved in the first transnational grassroots political movement to span the U.S.-Mexican border.

Late in the month of August 1908, around 7:00 p.m., Lázaro and John set off separately to Los Angeles’ Southern Pacific station. They left surreptitiously. Neither man risked buying a ticket. Instead, they rode “the vestibule of a passenger train from Los Angeles to El Paso, a practice of the more daring ‘hoboes.’” Their unanounced departure and the modesty of their chosen means of transportation were in tune with the circumstances. These men were heavily watched.

The Mexican government was exploring all available means of neutralizing key members of the Liberal Party residing in the United States, and Lázaro was amongst their best-known agitators. And it was not only the Mexicans who were being watched.

In the spring of 1908, the circle that met at the Noel home had set up an office dedicated to making propaganda for the Mexican cause, the liberation of the Mexican political prisoners, and to purchasing guns for the revolutionists who rose up in June of that year. They rented a space in the San Fernando Building, on the corner of Fourth and Main, and called themselves the Western Press Syndicate, with John Murray as President, and John Kenneth Turner as treasurer. Financial support came from Elizabeth Trowbridge, whose name did not appear in order to avoid trouble with her family.

The operation was pretty much run by Elizabeth and Ethel, though, since on May 8, John Murray secretly left to Mexico, in an attempt to make a journalistic exposé that would be a blow to Díaz for American public opinion. Murray managed to give the detectives of the Furlong Agency the slip, but Elizabeth, Ethel, and John were constantly being watched:

Spies…they followed us everywhere. Elizabeth was more spy-conscious than I was. They enraged her, but they also made her jumpy, over-cautious. My method was to ignore them, hers to be violently aware of their every move. Sometimes I’d get tired of crossing streets in the middle of the block, darting around corners or into buildings. I’d protest, or try to ridicule. But nothing could change Elizabeth. After all, her way was probably more fun.

At bottom, Elizabeth was more worried about her family than about the spies. But the young women soon became plenty aware that the spying had serious consequences for their Mexican friends, and for the movement as a whole. Their experience with the spies, which became increasingly more threatening, brought home the degree of collusion that existed between their government and the Mexican dictatorship.

By June of 1908, the two women had begun taking serious risks.

Rapidly Elizabeth and I were losing our romanticism and becoming realists. In the days after our jail experience we had said farewell to Fernando Palomarez and Juan Olivares separately in the San Fernando Building as they prepared to leave for Mexico and take part in the uprising. Elizabeth furnished money to buy guns. She spent her time between the Noel home and the Western Press Syndicate, with spies on her trail, the last ominous letter from her mother in her purse and a vast purpose in her heart.

The activists for the Mexican cause had been under a lot of stress prior to Lázaro and John’s departure. On June 25, the very day that John Murray returned from his Mexican trip, the Liberals launched an attack on the border towns of Viesca and Las Vacas, led by Praxedis Guerrero and Francisco Manrique. As in 1906, this attack was meant to trigger a wide-spread revolt. Unlike 1906, though, key members of the Junta — Ricardo, Librado, Manuel, and Antonio — were in prison during both the planning and execution of the revolt. Ethel and Elizabeth played a cameo role in the plot: they had accompanied María Brousse, Ricardo’s lover, to a prison visit and helped her smuggle secret instructions to Enrique Flores Magón. These were later intercepted. Indeed, the Mexican Liberals were deeply infiltrated, their rebellion was expected, and it was easily put down, with Liberals imprisoned and summarily shot in a good number of Mexican towns. Ricardo and his comrades were put in isolation from the outer world at the LA County Jail (“incommunicado”), and the American group had to act on its own, with no consultations with the Junta.

John and Lázaro’s trip was a bold attempt to keep the movement alive politically and to move to the offensive at the level of public opinion and propaganda. John Murray’s articles on Mexico for the International Socialist Review, though impressive in some ways, failed to have a substantive impact on public opinion. There was despondency and despair in the Liberal camp.

This is how Ethel recalled that period:

John Kenneth Turner was doing some hard thinking those days. He spent a lot of time talking to de Lara. Then he consulted Elizabeth. Before long the plan that was to work, and that incidentally would help to shape Mexico’s future history, was born. John and de Lara would go to Mexico together. John would present himself as a buyer from a New York firm — as a tobacco buyer in Valle Nacional, a buyer of sisal hemp in Yucatan and Quintana Roo. De Lara would go along as his paid interpreter and guide. Elizabeth agreed to pay all expenses.

Cognizant of the persecution that their movement faced, John and Lázaro’s mission was kept completely secret, and it was known only to the closest circle of collaborators — Ricardo, Antonio, Librado, and Manuel (all in prison), and Ethel, Elizabeth, John Murray, the Noels, the Harrimans, and Hattie Shea, who was Lázaro Gutiérrez de Lara’s American-socialist wife. Even so, skipping town quietly was of utmost importance. Lázaro was a wanted man in Mexico, and he needed to enter the country with an assumed identity. So skipping town was a way of giving the slip to the consular spy network.

But there was also a second attraction for “riding the trains.” In those days, the image of American freedom had come to be connected with free travel. As historian Frederick Jackson Turner had declared, the colonization of the West was over. There was no more homesteading and no more Indian wars. The lawlessness of the “Wild West” had given way to development, the power of the Trusts, and the rule of law.

But, there was still some freedom left in the American West, and it was expressed, at least in part, in freedom of movement. Intense union activity occurred alongside vast labor migrations, not only because of the tremendous influx of migrants from abroad, but also because of the way in which people hopped between jobs. In such a context, “riding the trains” came to stand for a kind of freedom. Many veterans of the Spanish American War rode the trains as hobos, looking for a new life after having seen the wider world. So too did the radicals of the IWW and the Western Federation of Miners, looking for brighter prospects. They rode the rails to flee the site of a strike, to look for new opportunities, or simply for the adventure. Mexican immigrants too learned to ride the trains, as soon as they gained confidence in their new lives as American workers.

Indeed, this image of freedom and self-reliance had become as important for Mexican members of the Liberal Party as it was for the true-blue American hobo. So, for instance, in her portrait of the Mayo Indian radical Fernando Palomares, Ethel emphasized precisely this aspect:

Sometimes he was a worker and sometimes a vagrant. He picked cotton in Texas near Austin. He went from Dallas to Shawnee, Oklahoma, still spreading the “powder” among Mexican workers. He rode the rods. He found that American tramps did not discriminate against Mexicans, but that they were all brothers. They would sleep in jungles, cook mulligans in cans, fry eggs on a shovel. He went to Nebraska. Slept in jungles until the police came with their clubs. He was a member of the IWW and went to their halls in the large cities.

The campsites where the rail vagrants slept, known as “jungles,” were places of equality between the races, where an individual might seek out new opportunities, as well as “spread the powder” (propagandize). These facets of a free life led Mexican union-men like Blas Lara to refer to the cars of the South Pacific Railroad as “my trains.” When he was once asked whether he needed money to go from California back to his native Jalisco to help his sick sister, Blas responded: “Not at all — I’ve got plenty of money. I’m going to ride on ‘my trains.’ Won’t be giving a cent to the Southern Pacific Railroad.” The same language was used some years later by Liberal organizer Rafael García, who rode the trains from California to Texas, and from there to Washington DC.

When crossing West Virginia, Rafael was caught and beaten up by the railroad controllers. This is what he had to say about that:

When crossing West Virginia, Rafael was caught and beaten up by the railroad controllers. This is what he had to say about that:

I missed “my train” in West Virginia because I was arrested by the rail companies’ “dogs” there. Perhaps because of the constant friction between miners and local authorities in that state, their dogs are even wilder than the ones down south. In the South the cops at least listened when I explained why workers are compelled to travel as tramps; here they tried to beat me when I started making the same explanations or whenever I responded to their insults. Even so they released me, after giving me heat, and after inspecting the letters and papers I had with me, demanding that I leave town at once.

Among Mexican radicals “riding the trains” as , came to symbolize a class and a political identity. The term trampa rolls the English term “tramp” and the Spanish term for cheating (trampa) into a single image, the worker as free-roaming trickster, and it was also used to form a new verb that referred specifically to riding the trains, trampear (to tramp). Poor workers had to know how to “viajar de trampa” if they wanted to survive, and the ties of solidarity between those who did were a mark of belonging. So, for instance, when liberal organizer Teodoro Gaitán was accused of bilking his comrades, one of the miners testified that

…López and Gaitán were at the station in Lourdsburg, N.M. when a mail train approached, and Gaitán said: “Tramp it (trampéalo); I’m taking the passenger train.” That sort of arrogance is unseemly in a person who is travelling with money garnered from his comrades’ contributions, and especially when that person presents himself as a proletarian who has to tramp the trains to travel.

The divide between the true worker and the opportunist was expressed in the class division between those who took the risk and hardship of traveling for free — hiding between or underneath the cars — and those who enjoyed the comfort of legality and a paid seat.

By “riding the rods” from Los Angeles to El Paso, John, and Lázaro gave the slip to a net of spies, police, and private detectives, but they also took the opportunity to immerse themselves in their political identity of choice, before taking on their disguises as enemies of the people.