From late September through October 1937, an estimated 15,000 Haitian men, women, and children were systematically murdered in the Dominican Republic on the orders of the country’s dictator Rafael Leónidas Trujillo Molina. Most of the killings occurred in and around the border between the Dominican Republic and Haiti, which share the island of Hispaniola. With such a high number of casualties in such a limited time, the Haitian Massacre, as it is known today, was arguably the largest mass murder in the Americas targeting people of African descent in the 20th century.

Growing up in the barrios of New York City in the 1970s and 80s as a child of Dominican immigrants, I was never taught about the 1937 Haitian Massacre in school or at home. My parents experienced the Trujillo dictatorship first hand, yet they never talked about this mass murder in their country of origin. They told me about the infamous spies called calieses, the network of informants, and the Stasi-like arrests, disappearances, and torture. But no massacre.

My archival unearthing at the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Presidential Library of a diplomatic communique from U.S. Ambassador R. Henry Norweb, who described the killings as “a systematic campaign of extermination,” marked the beginning of my journey as part of the Dominican diaspora to respond to the memory of the 1937 massacre. This undertaking was partly driven by the need to come to terms with my romanticized identity of what it meant to be an ethnic Dominican in the United States, but I also gradually came to the realization that for this event, I belonged to the descendants of the perpetrators with a responsibility to tell the story, to remind the world that these poor black Dominican and Haitian lives mattered.

|

Trujillo, who held power from 1930 to 1961, was a light-skinned mulatto from a working-class family in the town of San Cristóbal. (Incidentally, his maternal grandmother was Haitian.) He rose to power through the National Guard, an institution created by the U.S. forces that had occupied the country from 1916 to 1924. From the Americans, Trujillo learned valuable counterinsurgency skills. The U.S. Marines applied their brutal techniques not only to Dominicans, but across the border to Haitians as well, during an overlapping occupation of the island of Hispaniola from 1915 to 1934.

As a historic route for runaway slaves, pirates, bandits, contrebandiers, and revolutionary insurgents, the border region had always existed beyond the reach of Dominican elites in Santo Domingo. For Trujillo, the porous border threatened to destabilize his government. It didn’t take long for the region to once again become an escape route, this time for exiles fleeing Trujillo’s repressive government.

In 1930, Trujillo was determined to succeed where Dominican elites and American occupational forces had failed: he would control the border region. But it would take seven years of his rule and precisely the right conditions for ethnic cleansing to emerge. First, Trujillo had to eliminate his opposition and consolidate power. Second, he had to wait for the American withdrawal from Haiti in 1934, which until then had served to check his power. Finally, he had to solve the historic and thorny issue of unresolved border limits that had bedeviled both nations since the 19th century.

By the time the Americans had withdrawn from Haiti in 1934, a Haitian-Dominican bilateral commission was already surveying the border. Beginning in 1933, Trujillo and his Haitian counterpart, Sténio Vincent, were meeting at the border and in their respective capitals to negotiate a border treaty. In 1935, both countries signed definitive border treaties. By 1937, the Dominican Republic and Haiti were enjoying a diplomatic honeymoon, yet the rapprochement did not last. Later that year, Trujillo unleashed his army and conscripted civilians to murder thousands throughout the border region and beyond. No single reason can quite explain his motives.

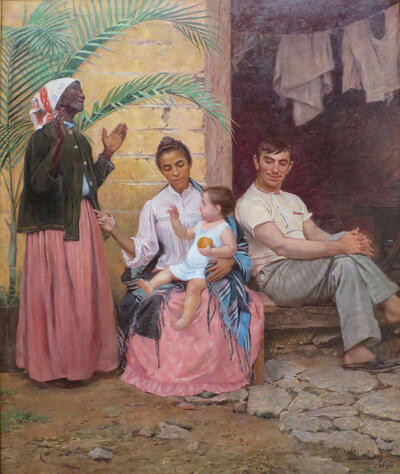

One view is that in cleansing the border of black Haitian bodies, Trujillo sought to whiten the nation. Like other Latin American governments, Trujillo may have been engaging in blanqueamiento, a policy of whitening to modernize and “improve” the nation. However, the policy was clearly not meant to de-Haitianize the nation, because the Dominican government continued to import thousands of workers from Haiti as sugarcane cutters during this time. The dependence on cheap Haitian labor would continue after the massacre, through the 20th and well into the 21st centuries.

Another view is that in a time of global food shortage during the Great Depression, Trujillo wanted to secure the borderland, colonize it, and transform it into a base for agricultural exports to domestic and international markets. Others contend that the massacre was aimed at destabilizing the Vincent regime, which gave refuge to anti-Trujillo exiles in order to replace the Haitian president with pro-Trujillo officials. Still others believe that Trujillo had grandiose ambitions of being a modern-day Napoleon in an age of imperialist and fascist global leaders and thus aimed to eventually invade Haiti. We will never know. There is no smoking gun. In retrospect, the massacre only served to disrupt the centuries-old, bicultural, bilingual Dominican and Haitian border communities that had existed beyond the reach and control of the Dominican state. As historian Richard Turits has written, the massacre on the border resulted in “A World Destroyed, A Nation Imposed.”

What we do know — through diplomatic correspondence and oral histories — is that the operation lasted several weeks and had been planned at least a year in advance. Men, women, and children who were black and deemed Haitian were arrested and taken to secluded areas of the Dominican countryside and murdered, mostly by machete to evade recriminations of a pre-meditated, large-scale operation by the army. The killings, the Dominican government would later argue, were a defensive reaction by “patriotic” farmers protecting their lands from Haitian “cattle rustlers.”

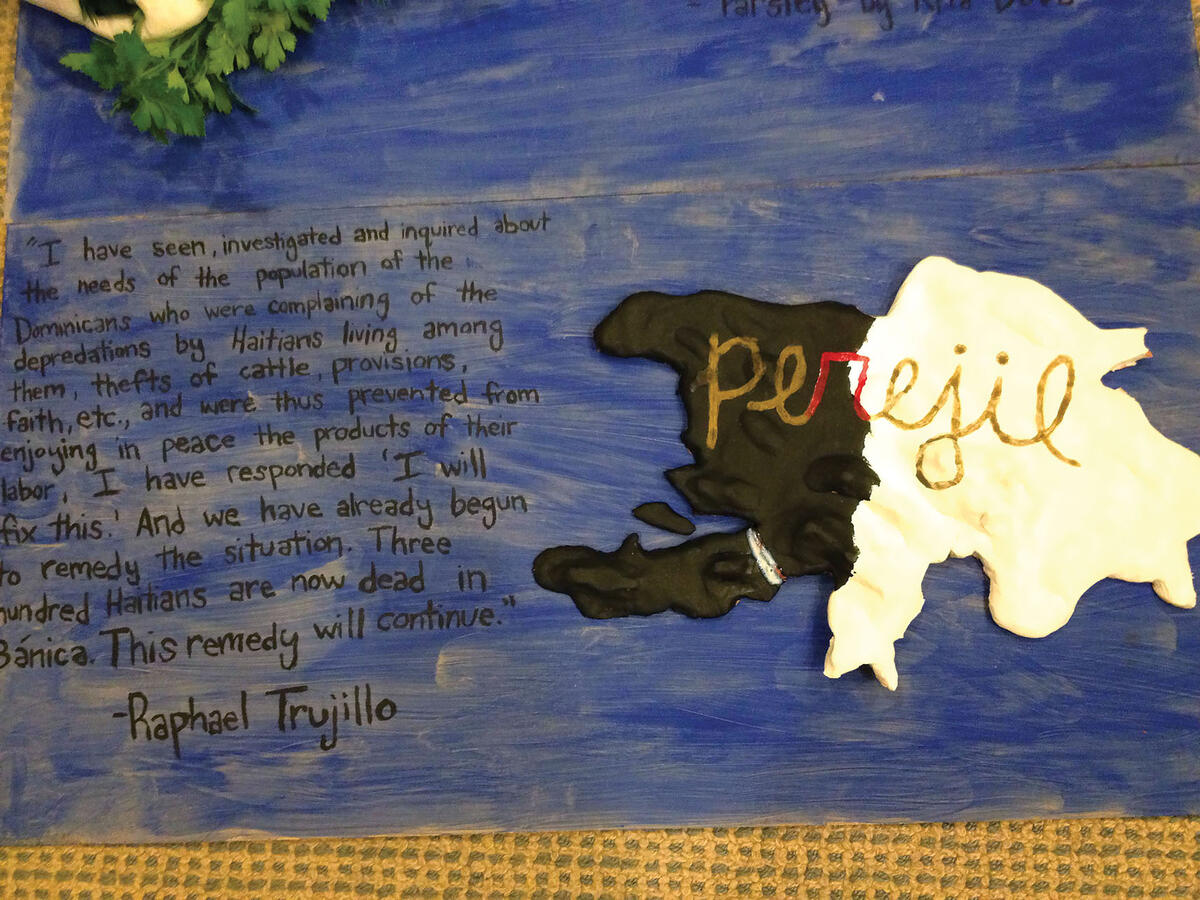

Historically known as El Corte (The Cutting) or El Desalojo (The Eviction) in the Dominican Republic and Temwayaj Kout Kouto (Testimonies of the Knife Blow or Witness to Massacre) in Haiti, the 1937 Haitian Massacre has also and most recently become known as the Parsley Massacre. Since Haitians speak Kreyol where the r’s are pronounced more softly, Spanish words with the letter r — like perejíl (parsley) — were used as a shibboleth. But in many cases, this linguistic litmus test was superfluous. Many of the “Haitian” people and communities that were targeted were, in fact, bicultural Dominican-Haitians and, thus, bilingual. It did not matter to their killers. Like scholars Lauren Derby and Richard Turits and journalist Juan Manuel García before me, I interviewed both survivors and perpetrators. Their harrowing stories of machete wounds, burning corpses, hunger and thirst, hiding in the forest for days, following grisly orders, and becoming refugees in Haiti were eerily reminiscent of 20th-century genocidal testimonies from around the world.

As mass murders go, the 1937 Massacre is an anomaly. Usually, the ideological campaign comes first, to prepare society for the impending violence against a targeted group. Not in the Dominican case. As Turits and Derby have written, the violence targeting Haitians and their children preceded the ideology. The massacre was followed by a state doctrine of anti-Haitianism that defined Haitians and Haiti as historic enemies of the Dominican Republic and a racially inferior “other.” In contrast, Dominicans were classified under the Eurocentric ideology of hispanidad and described as white, Catholic, and of Spanish descent.

Anti-Haitianism began as a Trujillo project, but it long survived him. Although the dictatorship ended in 1961, the ideological infrastructure developed over the two decades immediately following the massacre was never eradicated. No counter-ideological movement took place to expose and eliminate anti-Haitianism. Neither Trujillo himself nor any high government officials were ever punished for this crime against humanity. No truth and reconciliation committee was ever assembled.At the same time, the Dominican government was making great strides to implement its plans to nationalize the border. This unprecedented government program called La Dominicanización de la frontera (the Dominicanization of the border) wrested a region from (and historically closer to) Haiti and transformed its identity and use. Following the massacre, government institutions were established, and Dominican colonists from the interior populated the border region. It was urban planning on the periphery: an institutional and demographic curtain that served as a bulwark against Haitian encroachment.

In the absence of official efforts to preserve historical memory and recognize the victims and survivors of the massacre, the Border of Lights social collective has been carrying out annual commemoration activities on the Dominican-Haitian border since 2012. The group, of which I am a co-founder, is a loosely organized collection of “artists, activists, students, teachers, and parents who have come together to breathe life to a tragedy long forgotten, for some, a tragedy they never knew took place.”

Every October, we return to the Haitian and Dominican border to engage with the past and commit to a process of bearing witness: something the Dominican state should have embarked on years ago, but has never done — not just for this atrocity, but for other state crimes. Assisting local organizations, Border of Lights conducts community outreach on both sides of the border. It supports leaders on the ground who seek to foster historic, resilient cross-border solidarity. Every year, Border of Lights also holds a candlelight vigil from the northern border town of Dajabόn to the border checkpoint. It is perhaps the only time that the victims of the 1937 Massacre have received such a collective and public acknowledgment of their murders. The sight of hundreds of candles converging in the darkness on both sides of the Massacre River is a powerful testament to the world and the living.

An even wider public is invited to bear witness by participating in the Border of Lights global vigil online. People from around the world send in questions about this little-known massacre and join us in solidarity by contributing photos of themselves holding candles. The idea, as first proposed by writers Julia Alvarez and Michele Wucker, was to illuminate, literally and metaphorically, this tragic episode on the Dominican-Haitian border. Through these efforts to remember and engage with the past, Border of Lights also reveals the opportunities that are lost when states fail to make a reckoning with their history and challenge perceived notions of difference between groups, which can have disastrous consequences.

Rather than publicly and rightfully recognizing the impact of anti-Haitianism during the Trujillo regime and dismantling the racist ideology through revisionist history post-1961, the Dominican Republic opted to elect one of the dictator’s highest-ranking officials, Joaquίn Balaguer, as president. Under Balaguer and subsequent governments, the state continued to import cheap Haitian laborers, while remaining uninterested in creating a path to Dominican citizenship for second-, third-, and even fourth-generation Dominicans of Haitian descent.

The nation’s failure to carry out a historical reckoning informed by the 1937 Massacre came to a head in 2013, when the Dominican Republic’s Constitutional Tribunal issued Ruling 168-13, which denied citizenship “to anyone born to undocumented residents.” The ruling disproportionately affected long-term Haitian residents and their Dominican-born children. In 1937, Haitians and their Dominican-born descendants were excluded from the Dominican border by the knife; today, they are excluded from the nation by the judicial pen. Ruling 168-13 — or La Sentencia — was (and is) discriminatory, despite the subsequent 169-14 Regularization Law that was created to soften the effects of the ruling.

In the wake of the 2013 ruling, members of the Dominican diaspora expressed solidarity with those most affected: Dominicans of Haitian descent. As Anthony Stevens-Acevedo, one of the main organizers of a November 2013 march in New York City, commented: “As foreign-born or foreign-raised Dominicans that have lived the immigrant life experience, in this case in the U.S., we share the same existential circumstances of Dominicans born to Haitian immigrant parents in the Dominican Republic, and I felt we needed to support their right to a Dominican nationality.”

Today, an entire generation of Dominican and Haitian descent — both inside and outside of the Dominican Republic — are willing to remember and respond to the memory of this 20th-century crime against humanity in the Americas and its legacy. They are committed to undertaking the labor-intensive, transnational logistical work of organizing across borders. Organizations like ReconociDo, Mudha, Border of Lights, We Are All Dominican, Dominican@s por Derecho, Fundosalud, People’s Theater Project, Centro Bonó, Solidaridad Fronteriza, Mosctha, and Comunidad de Religiosas Hermanas de San Juan Evangelista work tirelessly and often in collaboration, advocating for a more just and equal society, irrespective of borders and nationality, but always underscoring how history and the lack of honest reckoning informs contemporary policies.

Edward Paulino is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Global History at John Jay College/CUNY and author of Dividing Hispaniola: The Dominican Republic’s Border Campaign against Haiti, 1930-1961 (Pitt Latin American Series, 2016). He spoke for the Center for Latin American Studies and the International Human Rights Law Clinic on February 16, 2016.

Border of Lights will be returning to the Haitian-Dominican border from September 28 to October 1, 2017, to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the Haitian Massacre.

For more information, please visit:

www.borderoflights.org

https://www.facebook.com/BorderofLights/?fref=ts