To make a documentary about beloved soccer star Andrés Escobar, who led Colombia to the 1994 World Cup and was killed at the apogee of that nation’s drug violence, the directors needed his friends, family and team to tell the story.

Of those who consented, nearly all warned that they would walk out of the interview at the slightest suggestion of a link between soccer and drug money. And yet, within minutes, unprompted, most began talking about narco-fútbol.

It soon became clear to Jeff and Michael Zimbalist that the short film they had set out to make for ESPN was not just about the murder of a soccer hero after he accidentally scored for the opposing team, eliminating Colombia from the World Cup competition. Nor was it simply an exposé of the involvement of drug money in Colombian soccer.

“We became less interested in who pulled the trigger and much more interested in what kind of society and circumstances would lead to the murder of a soccer player for a mistake on the field,” said Jeff Zimbalist.

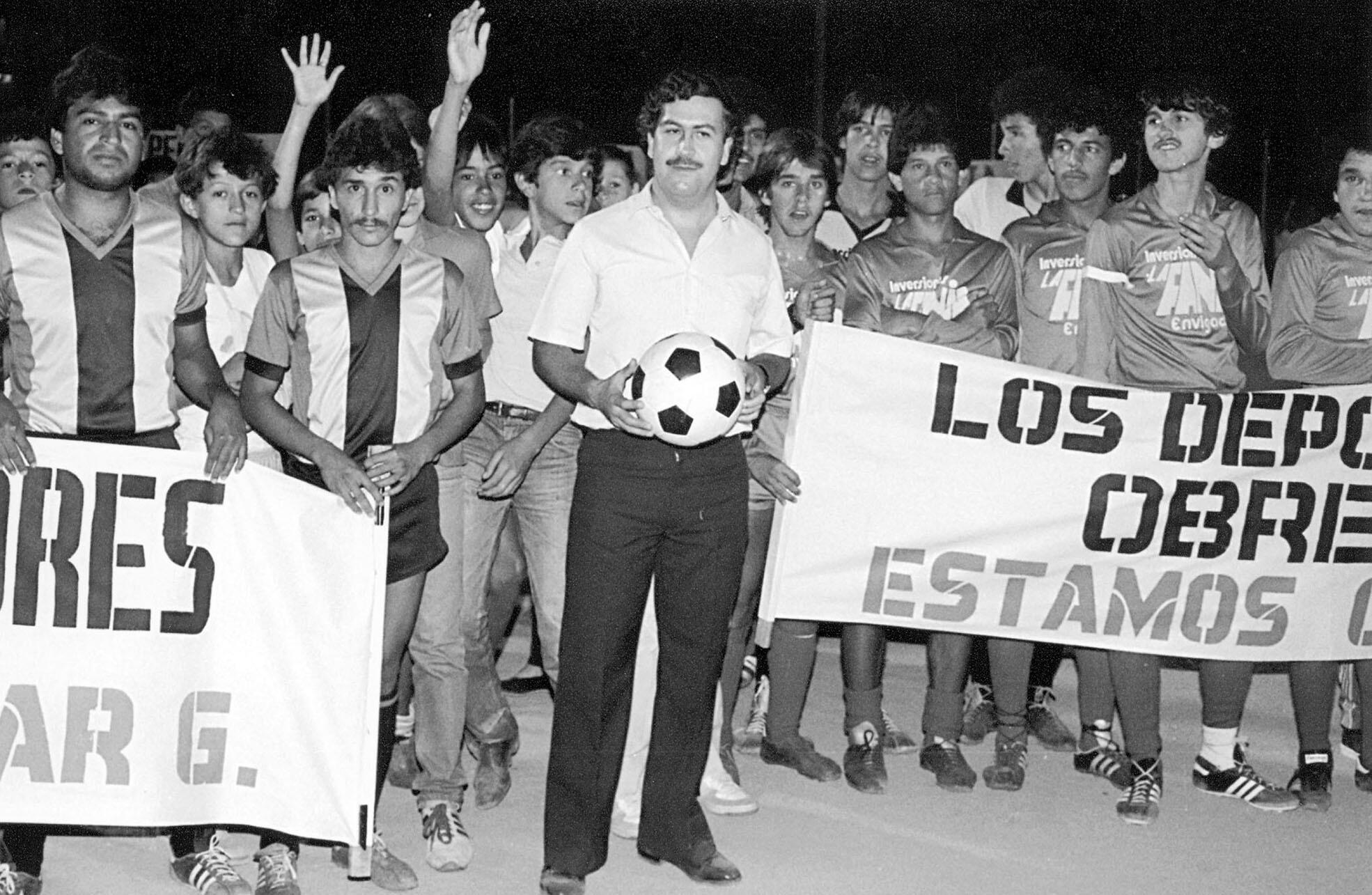

To understand the societal conditions in the Colombia of the early 1990s, they probed the unlikely entanglement of two unrelated men who shared a last name and a love of fútbol: the idealistic young “Gentleman of Soccer” and the nefarious narcotics kingpin Pablo Escobar. Ultimately, “The Two Escobars” transcends both its namesakes to tell the story of a wounded nation.

Since airing on ESPN in June, “The Two Escobars” has been released in movie theaters and featured at the Cannes, Doha, San Francisco and Bogotá film festivals, among others. With rapid-fire cuts and pulsating music, parts of the film have the feel and pace of a high-stakes soccer match, while the calm, often poetic, testimonials of those connected to Pablo and Andrés bring them and the era all too vividly to life.

As the head of the Medellín Cartel, Pablo Escobar was the most powerful drug lord in Colombia from the mid-1970s to the early 1990s. In those years, both U.S. demand for cocaine and Escobar’s wealth seemed limitless. Investing in Colombia’s Atlético Nacional soccer team allowed the drug lord to combine his billions of illegal dollars with his lifelong passion for soccer in the ideal money-laundering scheme.

With Escobar supplying the funds to recruit foreigners and to retain the best local players, the team began to win, and it kept winning. For the first time, a Colombian soccer team was competing at the international level. By the time the team won the South American championship, soccer had become much more than a game. It was the country’s pride, hope for millions living in desperate poverty, positive international recognition for a nation that had become synonymous with drugs, violence and guerilla warfare. Rich and poor, paramilitaries and guerillas, politicians and drug traffickers cheered for Atlético Nacional.

“Our country is very proud of you,” then-President César Gaviria said in a recorded phone conversation with striker Faustino Asprilla. “You have given Colombia a good name.”

Yet without drug money, in the words of Atlético Nacional’s coach, “Colombian soccer didn’t exist.”

In the film, Andrés is portrayed as impossibly good, a saintly figure. But Pablo Escobar becomes flesh and blood. Jeff Zimbalist said he hoped to show the narcotrafficker as both “devil and angel.” He wanted the audience to see the side of Escobar that is unfamiliar and incompatible with his better-known image as a murderous thug. When Escobar saw hundreds of people living on the edge of a garbage dump, living off refuse, he built them houses. With his ill-gotten riches, he constructed schools, health clinics and soccer fields. Many Colombian soccer players learned how to play on those fields and grew up admiring Escobar and feeling beholden to him.

Yet, to get in Pablo Escobar’s way was to invite death. Anyone who happened to be nearby was collateral damage. Escobar is often said to have risen to the top not because he was the cleverest but because he was the bloodiest. There is no official tally, but by the estimate of Pablo’s right-hand man, the Medellín Cartel killed 4,500 people. When a rival cartel boss bribed a referee to ensure that his team beat Atlética Nacional, Escobar ordered the referee’s assassination. When presidential candidate Luis Carlos Galán called for the extradition of drug traffickers to the United States, Escobar had him killed. When Galán’s successor, the future president César Gaviria, appeared to be doing well in the polls, Escobar had a bomb placed on a plane the candidate was thought to be taking. Although Gaviria was not on the plane, 110 people were killed in the crash, among them two Americans.

These high-profile attacks triggered a 15-month-long manhunt carried out by U.S. Special Forces, the Colombian National Police and an alliance of drug traffickers known as Los Pepes (Los Perseguidos por Pablo Escobar, People Persecuted by Pablo Escobar). Escobar was finally found and shot dead on December 2, 1993, seven months before Andrés’ death. Some say that if Pablo had still been alive, no one would have dared to risk the kingpin’s wrath by murdering the unlucky soccer star.

Narco-fútbol died with Pablo and Andrés Escobar. It became too visible to launder money through teams. Without the infusion of illicit funds, the nation’s soccer clubs began to disintegrate. Of Colombia’s 14 teams, 12 are now on the verge of bankruptcy, and Colombia has not reached the World Cup in the years since 1994. The Colombian drug trade, however, did not disappear. The rival Cali Cartel quickly came to dominance after Pablo Escobar’s death, and when it fell, another took its place.

Violence in Colombia has ebbed since the Escobar years. The homicide rate has halved, though it remains high. Mexico is now the main transit route for narcotics destined for the United States, and it has taken Colombia’s place as the battlefield in the War on Drugs. In the past three years, drug-related violence has killed an estimated 28,000 people in Mexico and, in another echo of the Escobar era, assassinations of Mexican politicians and journalists are on the rise.

Meanwhile, the U.S. appetite for drugs persists unabated.

CLAS held a screening of “The Two Escobars” followed by a question-and-answer session with director Jeff Zimbalist on October 11, 2010.

Sarah Krupp is a graduate student in Latin American Studies at UC Berkeley.