When Cata Flores found out she was pregnant, she was alone, broke, and living in a small town outside of Santiago, Chile. She didn’t know what to do, but she did know one thing: she couldn’t bring a child into the world without any resources or support.

She wanted to get an abortion, but that’s complicated in Chile, where terminating a pregnancy is illegal under any and all circumstances, including rape and to save a woman’s life. She couldn’t afford to fly out of the country to get an abortion, but she also didn’t have enough money to get the procedure from a safe, but illegal, local provider. Down on her luck and scrambling for options, Cata did what many poor women in her situation do: she found someone cheap.

“I was very irresponsible,” she said. “I went to a woman who gave me an unsafe abortion. I don’t know what she did, but in the end, she didn’t abort it.”

Three months later, the contractions began. Cata made her way to a public hospital in Santiago and gave birth to a premature baby. He was frail and slight, with a delicate chest that lurched whenever he gulped for air. For two months, Cata paced up and down the hospital’s bleak halls, watching her baby struggle to breathe through jagged gasps. And then one day, after months of fighting, he died.

“I aborted like a poor woman,” she said, reflecting on the experience years later. “And lived through what a poor woman lives through… This is my trauma.”

I first heard Cata’s story on a warm evening after dinner, in a dusty rural town near Santiago. I was in Chile researching an article about abortion, and I wanted to interview Cata about her job as a volunteer activist at a controversial pro-choice organization. I expected her to talk about her hands-on work with women; I wasn’t expecting her to tell her own abortion story.

Listening to Cata, an idea that had been taking shape in my mind solidified. Many of the people I interviewed told me that Chile’s abortion laws mainly impact poor women who can’t afford safe alternatives. I wanted to find out if this was true.

At the time, Cata was working as a volunteer at the Línea Aborto Información Segura (Safe Abortion Information Hotline), run by Lesbianas y Feministas por el Derecho a la Información (Lesbians and Feminists for the Right to Information). The organization provides medical information about misoprostol, an ulcer medication that induces miscarriages and is clandestinely sold on the Chilean black market.

The hotline’s work fascinated me. They seemed to be operating in a tenuous, legally gray limbo: technically, their work is lawful, but only if they strictly adhere to a set of guidelines that prevents them from asking callers questions or addressing them in the first person. The only reason they’re able to provide any information at all is because similar guidelines are available online from a variety of organizations, including the World Health Organization (WHO).

But more than information about misoprostol, I wanted to know statistics: How many women abort annually? And how dangerous are these procedures?

I quickly found out that my questions were a little too ambitious. The government doesn’t compile any official numbers on abortion. One of the only comprehensive, data-driven studies about abortion in Chile that has come out in the past 20 years is a 1994 study by the Guttmacher Institute, a reproductive health nonprofit. The report estimated that the country’s annual number of clandestine abortions hovered around 160,000. Other approximations range from 60,000 to 200,000 per year, in a country with a population of 17 million.

“The experience of having to obtain an illegal abortion can be traumatic,” hotline volunteer Emily Anne said. “Some of the women who call us will be really upset. They’ll be crying, or they’ll be really scared to talk to us… You don’t want to talk to them in the third person because it sounds cold… I try to express sympathy through my tone of voice.”

It’s somewhat baffling to think that, 70 years ago, Chile’s abortion laws were more liberal than they are now. Between 1931 and 1989, therapeutic abortion — terminating a pregnancy to save a woman’s life — was legal. But that changed in 1989, when General Augusto Pinochet criminalized all forms of abortion shortly before the end of his 17-year rule. According to the Center for Reproductive Rights, Chile is one of 29 countries in the world that ban abortion without any explicit exceptions. In Latin America and the Caribbean, it is one of only five countries where abortion is absolutely prohibited, even when the procedure could save a woman’s life. The others are the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua.

Contraceptive methods includ-ing condoms, birth control pills, and Plan B are available to women, but they’re expensive. In 2002, the Chilean legislature passed a bill that allowed pharmacies to distribute Plan B, but many refused to comply for religious reasons.

And then came misoprostol. The pill was originally created to be an ulcer medication, but now it’s used in countries worldwide to provide women with non-surgical, first-trimester abortions. According to the International Consortium for Medical Abortion, more than 26 million women around the world safely aborted with misoprostol in 2005. Misoprostol is sold on the black market in Chile, but it’s technically legal. Pharmacies choose not to sell it, some speculate for religious reasons.

And then came misoprostol. The pill was originally created to be an ulcer medication, but now it’s used in countries worldwide to provide women with non-surgical, first-trimester abortions. According to the International Consortium for Medical Abortion, more than 26 million women around the world safely aborted with misoprostol in 2005. Misoprostol is sold on the black market in Chile, but it’s technically legal. Pharmacies choose not to sell it, some speculate for religious reasons.

This makes it impossible for women to buy the drug over the counter. Instead, it’s sold clandestinely and is easy, but not cheap, to obtain. A full dosage of 12 pills costs about $250. In 2011, the average monthly salary in Chile was $800, according to a survey by the National Institute of Statistics. In spite of the pill’s high price tag, this method has “made a huge impact on the way that women abort,” said Fanny Berlagoscky, a Chilean midwife and feminist.

But perhaps the most revolutionary part of misoprostol is that it can’t be physically detected. That means if a woman suffers health complications after taking the 12-pill dosage and has to be taken to the hospital, it is impossible for doctors to tell that she has taken the medication. This protects her from arrest and possible imprisonment, unless she confesses to using the pills herself.

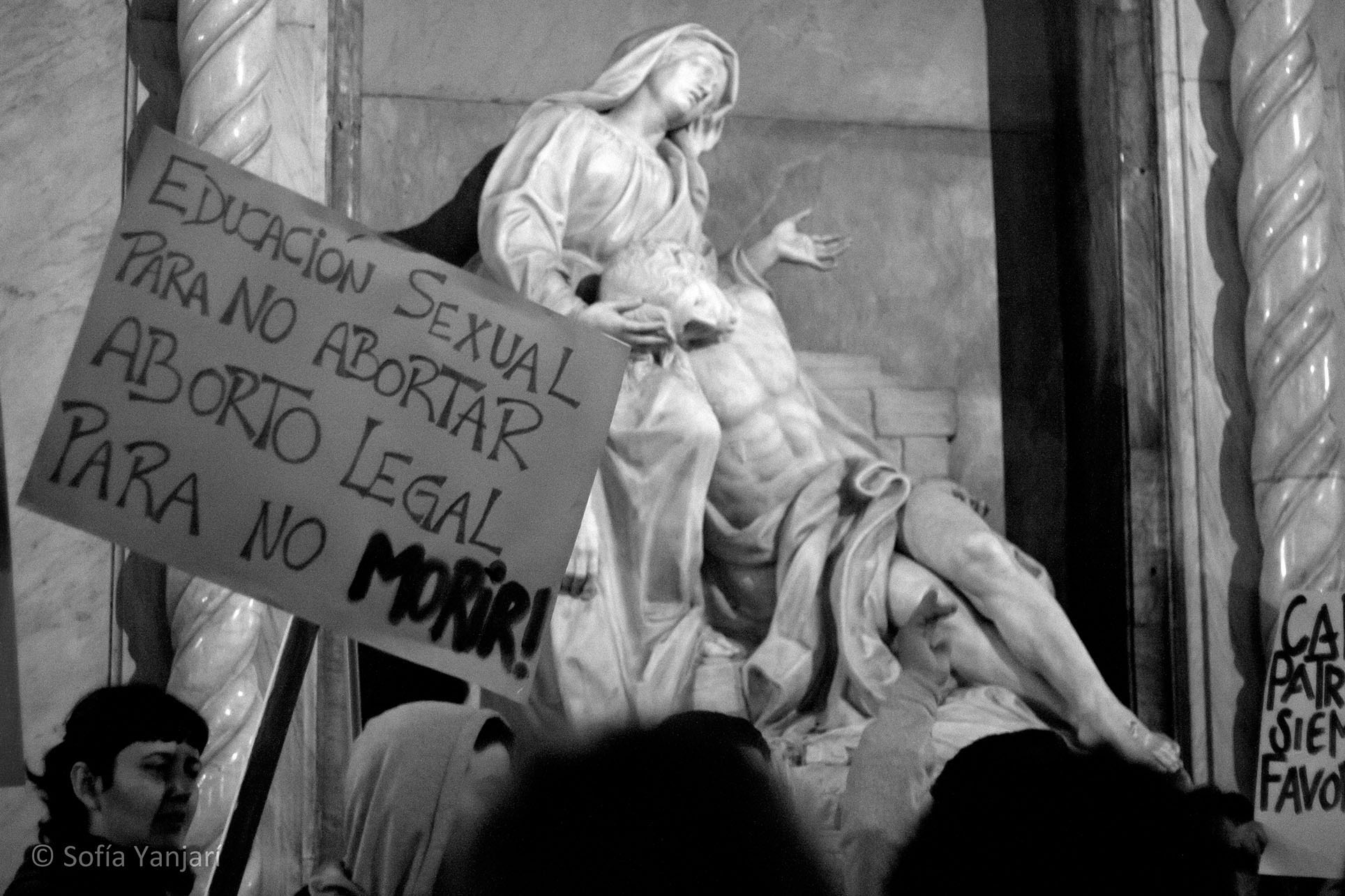

As I continued my research in Chile, a few themes consistently came up. Almost everyone I interviewed said that the country’s strict abortion laws are a direct result of its Catholicism and political conservatism.

“It’s a profoundly conservative country,” Cata said. “Much more than Argentina, much more than Uruguay… The participation of the church in the conservative movement has always been important in Chile.”

Other people talked about Chile’s culturally pervasive chauvinism, or as the Chileans call it: machismo. Alejandro Guajardo Arriagada, the Executive Director of the Chilean reproductive health organization Aprofa, laughed when I asked him about machismo. “Where on earth do I begin?” he chortled, explaining that in Chile, it’s common for men to be served dinner first, often before the women who labored over the meal. What’s more, most men aren’t even aware of these unequal power structures, he said. They simply think that’s the way things are.

This cultural attitude impacts women of all socioeconomic standings, explained Eduardo Ramirez,* a doctor and illegal abortion provider. “This doesn’t just affect poor women,” he said, from his spacious apartment in downtown Santiago. “It affects everyone.”

Dr. Ramirez serves about one patient a week. He doesn’t provide surgical abortions. Instead, he meets with women seeking to abort with misoprostol, buys them the pills out of pocket, and checks up on them every couple hours. He offers in-home visits after they take the medication and support in case any medical complications arise. He provides free services, so the women he sees come from all socioeconomic classes. But more often than not, the women who come to him completely alone aren’t poor.

“They come from wealthy, conservative communities,” he said. “They’re usually very Catholic. They don’t feel they can tell anyone in their lives about what’s going on. So, they do it all alone. That process can be profoundly psychologically damaging.”

The more people I talked to, the more I was convinced that Dr. Ramirez was right. The process of seeking out an illegal, highly taboo procedure carries an intense amount of mental strain, regardless of a women’s socioeconomic standing. It’s hard to split hairs over trauma.

“Women are smart,” he said. “They’re the reason I have faith. They are always adapting, always looking for better options. Misoprostol has made abortion safer, and now, that’s what most women do. They’re not dying like they used to. We’ll see what they come up with next.”

*Dr. Eduardo Ramirez’s name has been changed to protect his identity.

Erica Hellerstein is a student at UC Berkeley’s Graduate School of Journalism. She received a Tinker Grant from CLAS to travel to Chile in the summer of 2013.