I first met investigative journalist Mónica González Mujica in Santiago in 2004 while producing “The Judge and the General,” a PBS documentary about the first Chilean judge to indict Augusto Pinochet for murdering and kidnapping political opponents. Chilean co-producer Patricio Lanfranco and I interviewed González six times during almost three years of filming. She is the brightest light, a beacon, among the hundreds of people I’ve interviewed in half a century of reporting in print and on public television. Her work has been pivotal in the struggle for truth and justice in Chile.

After studying Latin American history in college and graduate school in the 1960s, I was hired to assistant produce a feature film in Chile during the 1970 presidential campaign. Dr. Salvador Allende, a long-time leader of the Socialist Party, won that election, enraging the Chilean right and high officials of the Nixon administration. The film, “¿Qué Hacer?” used documentary footage and fictional characters to explore, among other topics, democratic versus revolutionary socialism. Chilean actors portrayed leftists of various persuasions. A leader of the Movimiento de Izquierda Revolucionaria (MIR, Movement of the Revolutionary Left) appeared as himself from prison. American actors played CIA spies conspiring to prevent Allende’s election. Berkeley’s Country Joe McDonald composed the film’s music and served as a Brechtian chorus.

After returning to the Bay Area at the end of 1970, I spent the next three years reporting U.S. efforts to undermine President Allende’s democratically elected government. I contributed to publications ranging from Foreign Policy to the Report on the Americas of the North American Congress on Latin America (NACLA).

On September 11, 1973, General Augusto Pinochet overthrew Allende in a violent military coup. Allende committed suicide in the presidential palace before soldiers could take him prisoner. In the following months, people I’d known were killed, forced into exile, or made to disappear. Jorge Mueller, a cameraman on “¿Qué Hacer?”, was kidnapped, never to be seen again. He may be among those tied to rails and dumped from helicopters into the Pacific Ocean. I am godmother to the son of a friend who survived imprisonment and torture.

According to the National Commission for Truth and Reconciliation (Rettig Commission), the National Corporation for Reparations and Reconciliation, and the National Commission on Political Imprisonment and Torture Report (Valech Report), between 1973 and 1990 a total of 3,227 people were disappeared or killed by the military government and its secret police, the Dirección de Inteligencia Nacional (DINA, National Intelligence Directorate), and more than 40,000 people were tortured and/or imprisoned.

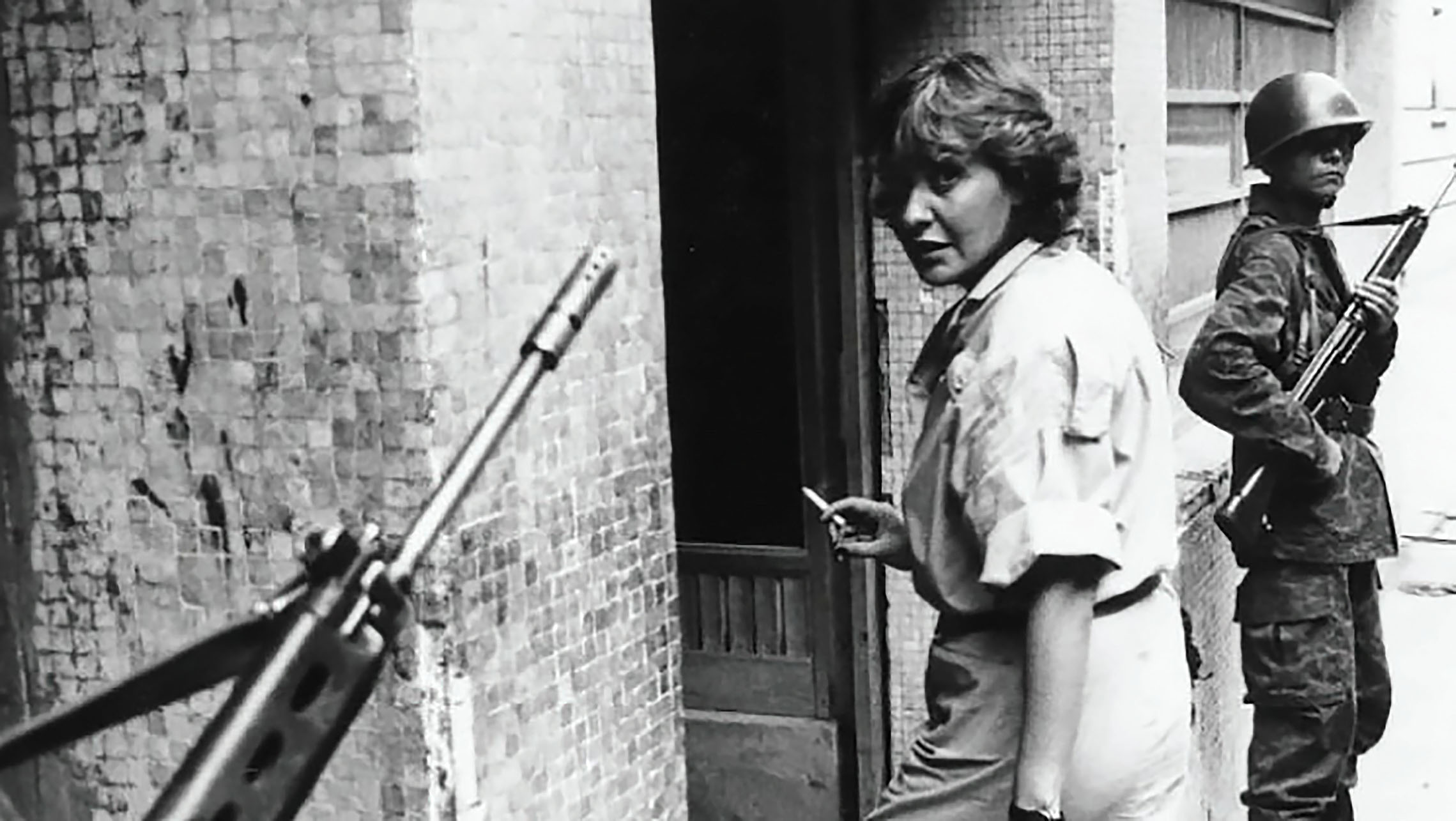

Mónica González was among tens of thousands of Chileans who fled into exile. Born in 1949, she had grown up poor and joined the Communist Party as a young girl. At the time of the coup, she worked for El Siglo, the Communist Party newspaper. In fear for her daughters’ lives, she sent them into exile and then escaped herself. She lived with her daughters in France until 1978, when she returned to Chile, “obsessed,” as she says, with the “death machine” of the Pinochet regime.

Her obsession has produced hundreds of investigative articles and seven books. She has also edited several leading Chilean publications. In 2007, with U.S. journalist John Dinges, she founded the Centro de Investigación Periodística (CIPER), a highly regarded investigative website, and served as its director until 2019. She resigned the directorship for reasons of health but is still president of the nonprofit Fundación CIPER. She reports freelance and frequently comments on television. Her work has received awards from around the world. In 2019, Chile honored her with its highest journalistic honor, the Premio Nacional de Periodismo.

Chilean filmmaker María José Calderón and I recently reviewed the transcripts of González’s interviews for “The Judge and the General” 2 and found her words more relevant than ever. In recent years, the struggle for human rights has suffered setbacks around the world, and Chile is no exception. When González learned that she’d received the Premio Nacional de Periodismo, she said that false news (falsas noticias) is now “a threat to democracy that threatens our lives.” Her success in countering false news over almost half a century provides an example for today’s human rights activists. Her courage and commitment are a tonic against despair.

Patricio Lanfranco and I first interviewed González on February 25, 2004, in the office of the Chilean magazine Siete+7, where she was editor-in-chief. I asked her opinion on the subject of our film, Appeals Court Judge Juan Guzmán Tapia, who was investigating Pinochet’s alleged crimes (at that time, judges led criminal investigations in Chile).

It was widely known that Guzmán had supported Pinochet’s coup against Allende, and at first, human rights activists had low expectations. Guzmán surprised them. Repeatedly threatened with assassination, he pursued a vigorous investigation and, on December 13, 2004, indicted Pinochet for murder and kidnapping.

Typically, Mónica González didn’t condemn, but tried to understand, Guzmán’s early support for Pinochet. Even after years of staring into the abyss, she still believed in the human capacity for change.

The death of Judge Juan Guzmán on January 22, 2021, makes the excerpts below especially timely. CLAS had a close relationship with the judge and published excerpts from his memoir in the Fall 2019 issue of the Berkeley Review of Latin American Studies, “At the Edge of the World: Memories of a Judge Who Indicted Pinochet.” We send deep regards and sympathy to his family.

***

Mónica González: I was one of the first people Judge Juan Guzmán Tapia called to testify because in 1986 I had made public, with Ricardo García and Patricia Verdugo, the contents of a tape we called “Chile: Between Sorrow and Hope.” At the end of that tape is something that had until then been completely unknown. It was recorded in September 1973, on the day of the coup d’état against President Salvador Allende. On the tape, Pinochet speaks the horrendous phrase, Matando la perra, se acaba la leva. Killing the bitch gets rid of the litter. 3

Judge Guzmán called me to testify with others to find out where we’d gotten that recording and to learn if it was true.

I spent about three hours with Guzmán then, and as he began to question me, I realized that he knew next to nothing.

He is the son of Juan Guzmán Cruchaga, a Chilean poet, and in high school, we had to memorize one of his poems. Generally one doesn’t like poems you’re made to read, but I really liked that poem, and it is forever imprinted in my mind. Part of it goes like this:

Una lámpara encendida

esperó toda la vida

tu llegada.

Hoy la hallarás extinguida.

A burning lamp

waited a lifetime

for you to arrive.

Now you’ll find it extinguished.

I thought the poem reflected our situation because we’d been waiting so long for a judge, but I saw few indications that Judge Guzmán would be up to the task. When I told him that, he said, “Well, I don’t want to be that extinguished lamp.”

I think that Juan Guzmán is like Bishop Sergio Valech 4 when he assumed control of the Vicaría de Solidaridad. Valech was, as he admits, a momio [mummy], a conservative, and yet he changed into an incredible defender of people’s rights. There’s a difference between decency and indecency, between sensitivity and negligence or selfishness. There are those who justify the bad, the deaths, regardless of where they come from. It could be a Communist who justifies crimes committed in the Soviet Union or, like here in Chile, where thousands and thousands of people justified the assassinations knowing they existed but without wanting to know.

There were also some who didn’t know what was happening because they were in their own world.

Judge Guzmán is not the only one, but he is an example. He was privileged. He likes to collect fossils; he likes ancient history; he’s refined; he has a French wife. He created his own refuge and buried himself there, and he had the luck not to be forced to confront reality. But because he is a decent, intelligent, and sensitive man, when he was confronted with reality, he had to decide whether to be a judge who does only the minimum or to commit himself and do the best possible investigation, and he did the latter. Thanks to his work, Pinochet’s immunity from prosecution was lifted on August 8, 2000, and that opened the doors so that today more than 60 killers of many Chileans are in jail. Without that lifting of immunity, we wouldn’t have the concept of secuestro permanente [permanent kidnapping] which allows for those people to be indicted and tried as long the bodies are not found. 5

Guzmán conducted an investigation in which he put together all the pieces with the help of the lawyers and especially the relatives, the most forgotten characters.

Elizabeth Farnsworth: You have said that some relatives almost became lawyers.

MG: These are the most forgotten characters. There are families that had to learn to be lawyers. They learned so much they could almost be attorneys today. There are cases of women who had very hard lives. You can’t live a normal life waiting 30, 25, or even 10 years for a husband who may not come back. They were young, and many remarried, because that’s life. And they had a really hard time with their new partners. They thought, “How can I fall in love again? What if he comes back?” For them, it was like killing the disappeared.

Some women started looking [for their husbands] — and they had to hear things like, “He left you for another woman, he was never detained. It’s a lie that he ‘disappeared.’”

***

In the February 25, 2004, interview in her office at Siete+7, González also discussed “Operation Colombo,” a 1975 DINA operation aimed at covering up the murder of more than 100 of the disappeared at a time when Pinochet’s government was under scrutiny for human rights violations by the United Nations, Amnesty International, and other international organizations. González had discovered the truth about Operation Colombo while investigating the assassination in Buenos Aires of General Carlos Prats, who had sought exile in Argentina after serving as Commander in Chief of the Chilean Army under Allende.

***

MG: In July 1975, newspapers like El Mercurio and La Nación had come out saying that those who had blamed the military junta for arresting and killing people had to bite their tongues. The “disappeared” had died because of killings among themselves.

EF: If you hadn’t gone to Argentina, we wouldn’t have learned the truth.

MG: The truth would have come out another way or someone else would have done what I did. I have a lot of faith in life, and I think that somehow things that are hidden below ground appear. I feel like I was just an instrument. I have faith that another judge, journalist, or lawyer would have done what I did later.

EF: But you opened that box….

MG: Because I am obsessive. It wasn’t by chance. The guy at the courthouse let me into a dark, dirty room all by myself, because who cared about court documents in Argentina during those years?

I had gone under precarious circumstances to investigate the assassination of General Carlos Prats. Argentina was coming out of a dictatorship. The courts were occupied by fascists. They would threaten you and describe in detail what they do to “women like you.” Then one day, the Argentine journalist Horacio Verbitsky stopped me in a corridor and said, “You are Mónica González, yes? Look for the case of Enrique Arancibia Clavel, 6 the spy case, and you’ll find what you’re looking for.” I would have to get authorization from a judge to see that, and it was difficult. I spent many days standing outside the judge’s house. It was winter in Buenos Aires. I started at 7:00 a.m.

Finally he gave in, and I was able to locate a room inside the judicial archives and find those boxes. I can see it as if it were today. They left me alone in this dirty place. I took the first box, and it was full of documents all jammed together. It was hard to open. I took a few things out and documents fell. The first things that came out were ID documents. I picked one up. It says, “Amelia Bruhn,” a woman I knew, a marvelous woman, a disappeared prisoner. There was her ID.

From then on I was frantic. I very quickly asked myself, “What should I do?” So I started recording. Very quickly I realized these are DINA archives. It’s the only file from DINA in existence. 7

To my horror, I saw ID documents from disappeared prisoners, handwritten letters that describe the butchering, the deaths, people who were being followed.

EF: You recorded for days?

MG: I could have stolen those documents, but they were legal documents. If I took them, they’d lose their legal value. This “legality” is after us, but still we follow it.

I tape and tape, and sometimes, I cry, sitting on the cold floor. It was very cold. I was there from 8 a.m. until they made me leave. No breaks. I tape and tape and cry, alone, because there are photos of bodies torn apart or when I read the story of my friend David Silberman. 8

It was the first time I saw it, handwritten. My friend. There was his death.

Those DINA files show there was a systematic organization for the assassination of opponents of the Pinochet government, a decision to eliminate them brutally and leave no traces. The files show how they organized a “simulacrum” [fake newspaper story] to pretend these 119 disappeared had run away to Argentina, when the truth was they were killed in Chile.

Some of those prisoners were dynamited, others thrown in the sea. I found names of the disappeared prisoners they’d killed in that way. There were also three names that didn’t appear on any list, and they became an obsession for me. It must have been six months until one day, while I was reading the testimony of a survivor, I found something that said, “…and González arrived together with the Andrónico Antequera brothers.” And for the first time [the name of] Samuel González appeared. 9 He had not been on the other lists [of disappeared prisoners].

It’s one of the most emotional stories for me because it was only because I’m obsessive that my search helped discover that child — he was a very young man without a father or mother, an orphan. His sister was a cloistered nun, and we found that nun, who came out of her cloister only once — to file a case for her brother in the courts. And I felt that day that Samuel González lived. I am agnostic, but I felt that God put me there to find that ID, as if saying, “Mónica, you can’t rest until you find him.”

In 1991, I found the man who had provided the list of names to those newspapers. His name was Gerardo Roa. He was chief of the Public Relations Department of the City of Santiago. I was then editor-in-chief of the newspaper La Nación. He received me saying, “What an honor.”

I said to him, “Close the door because what I have to say is private and I don’t want anyone to interrupt us.” Then I showed him the documents and asked, What do you have to say about this? The guy turned pale and began to perspire, and suddenly, he fainted.

I got him water, and he started to recover and said, “Yes, Manuel Contreras [the head of DINA] personally asked me to deliver the documents. I was in Rio de Janeiro then and had contacts with the newspaper O Dia, so I did it. We paid for that edition.”

I said, “If you will declare this to the Rettig Commission, I won’t publish it, but you must tell them everything. If you do that, I won’t publish. What’s important is that you establish, for potential prosecutions, how and who gave you the order, what information you gave to the newspapers, and how much you paid and to whom.”

I had it all planned [for him to reveal the information on that same day], but he was having a hard time breathing. He was afraid he’d have a heart attack. He was very fat and sweating profusely. So I told him, “You can’t do it today. I will come pick you up on Monday at 11:00, and nobody will know. I assure you that privacy.” Luckily, we are compassionate. We are different from them, and we celebrate that difference.

So I went back on Monday. I was received by a composed man. He let me into his office, opened the drawer, and took out a recent photo of my daughters in Paris, and he said, “Do you want them to stay alive?”

He worked for a democratically elected government but still had that job. I spoke to his boss, who said, “Don’t publish, you’ll get killed.” I told him, “You have to fire that man.”

In spite of the threat, I immediately published the story in La Nación, including all the details of Roa’s participation.

***

González is emphasizing here that her encounter with Gerardo Roa occurred early in the democratically elected government of President Patricio Aylwin, a Christian Democrat. Even in 2004, with Pinochet under investigation for murder, she believed much more had to be done to uncover the truth about his death machine, but she nonetheless praised what had been achieved thus far. Some people were more critical.

***

MG: I respect all opinions, but personally, I feel proud every morning for what we have achieved. But do you know what is sad? If we don’t appreciate the work that we have all done, the relatives won’t heal their wounds. Because if we keep saying we haven’t done enough, then what else should we have done? There’s no other country that had a dictatorship in South America that now has so many military officers in jail like we do in Chile, and there will be more.

Did you know that there wasn’t a single day during the dictatorship when there wasn’t a complaint that included the name of a torturer, the address of a secret detention center? All that is the history of Chile, and it’s now in the courts. It’s our work, our achievement. I feel proud in front of my daughters. A lot of bad things happened, but we’ve left something beautiful to our children and grandchildren.

***

The following excerpts are from an interview in González’s home on September 24, 2004.

***

EF: One of your first breakthroughs was when Andrés Valenzuela came to speak with you.

MG: Yes. It happened in 1984. Valenzuela was the only uniformed soldier, the only member of a security organization, who decided, while still in uniform, to go and say, “Here I am. I tortured. I murdered. I broke the bones of a corpse. I burned a corpse. The smell of death haunts me. I go to sleep and wake up smelling the dead.”

EF: Why did he come to you?

MG: He says — and I think it’s true — that it was because I had implicated Pinochet in financial scandals. Until then, I didn’t know that for the right wing, to be caught in “illegal enrichment” is something worse than killing. I had also written an article about heads of security organizations who were assassinated in a power struggle that took place in those years, and Andrés Valenzuela said to himself, “If she is moved when a member of a security force, a person who has tortured and murdered people, is himself killed, then she is the only person who can hear me.” He approached me when I was working for Cauce magazine. He didn’t want to escape or save himself. He wanted to tell his truth.

EF: I’ve heard that you had long wanted to know how a person can do what Valenzuela did. What did you learn?

MG: Valenzuela changed my life. Because of the horrors he related, I realized that I had an unprecedented truth. He tells me, “I killed this person. I kidnapped him from his house or from the street, and we tortured him, hanged him from the shower, applied electric shocks.” He doesn’t omit any details. For example, [he said things like] “The body was so stiff that I had to use machetes to cut the bones that were so burned they had a burgundy color.”

It was hard to breathe, but one had to keep on listening. There was something marvelous about him wanting to talk, but at times, I was blinded. I felt such hatred [I thought], “I’ll let this man talk, but then he should be killed.” Then, at one point, I said [to myself], “Let’s find out who this man is.” I began to ask him about his childhood, starting with: “Are you married?” I will never forget what he said.

“Yes.”

“Do you love your wife?

“Yes.”

And then, “Why, if you love your wife, are you doing something now that is going to cause your death?” Because he had told me he wanted to talk and then go back to his regiment and be killed...

“Because I don’t deserve to be loved.”

“Do you have children?”

“Yes.”

“Do you hug them? Do they hug you?”

“No, in the last six months, I have been a bad guy, a violent man. I don’t want to be loved.”

“Why not?”

“I don’t deserve it. I smell like death.”

“Excuse me,” I said. “How long has it been since you’ve made love?”

He’s taken aback and asks why.

“I’m just asking. Do you make love?”

“Why do you want to know?” he asks.

“Do you make love with your wife?”

“No, it has been a long time.”

“And with prostitutes?” And that is the key because he tells me, from his gut, “No, not even a prostitute deserves to make love to a man like myself.”

And he cried. He shed tears, but it was a strange kind of crying. And so that is when I go back to his childhood.

“Tell me how it was when you were a child.”

And it was then that Andrés Valenzuela, a man who spoke of death and corpses, began to shine, to talk about the boy growing free in the countryside who dreams of becoming a policeman, who dreams of being a man who would keep peace and order, but an order without bars, a man who would have “the bad guys,” the thieves, the killers, under control. He was a good guy.

EF: What changed him?

MG: I asked, “Why did you become exactly the opposite? Why did you end up killing?” And he said a marvelous phrase, “Sin querer queriendo, not wanting to, yet wanting to, señora.”

He always called me “señora.”

And I did not understand “sin querer queriendo.” Then he keeps talking and tells me that he’s the son of peasant farmers. He joined the army as a foot soldier. And one day, a few days after the military coup, they asked him to guard some prisoners who are completely black and blue and dying because they’ve been tortured. Another day, he sees a woman being raped, and he feels like throwing up and goes to vomit. But the second time he sees a woman being raped, he gets turned on. He gets hard. He does not feel like vomiting. When he sees that woman being raped, he wants to participate, but he says “no.”

But the third time, he does it, “sin querer queriendo, señora.”

“I saw myself one day doing what I never thought I would do,” he said.

That is the death machine that obsessed me. Andrés Valenzuela taught me something I didn’t know: no one was born to be a killer, no one was born to be a traitor, and no one is born brave. Life conditions you. Your history will determine the place in history you will occupy. Valenzuela found himself in a moment in history where he had neither the strength nor the power to reverse history.

EF: How could you do your work with the threats, without fear, without stopping? Where did you get the courage?

MG: How can you think that I wasn’t afraid? I’m sorry to say this, but I had to wash my underwear many times every day. I peed, I soiled myself with fear. I was constantly afraid. I am not unusual. I am not a superwoman. I am totally normal.

EF: Why didn’t you stop? Many did…

MG: I’ve been asked that many times. Many more times than you can imagine. Because in order to fight against vanity, which is already present, I haven’t even collected my articles. I haven’t gathered all of them together. It’s a way of saying, “I don’t know what I have done.” But my memory is like a hard disk. When I think about how involved I got during an investigation, working 18 to 20 hours a day, I don’t know how I did it. I have only one explanation or various explanations — one, but with various factors. You can defeat fear when you have an ethical strength, moral principles. I was always afraid. I don’t remember bigger fears than I felt at those times, a paralyzing fear.

EF: Where did that strength come from? Your father’s politics? 11

MG: No, no, from the compañeros who died. When you are part of a group since you are 14…. I came from a poor family. My father died when I was 13. My shoes had holes. You suffer the cold, and a friend comes to you and says simply, “Mónica, I brought you this, a pair of shoes and panties, a brassiere.” It was the first brassiere of my life and a pretty blouse. It was a time when we young communists. Girls wore no makeup, long hair but no fancy stuff. They brought me books.

EF: They were compañeros from the party who gave you that?

MG: Yes, I became a Communist at age 14, 12 and we were a marvelous group. It was to feel part of a big current that was meant to change injustice in Chile. But your name was not going to be carved in marble. You were part of a river that had an enormous nondestructive force. You were among those who had died, who had done thousands of things anonymously. You were just one more in an important river.

The friends you sang with! I love to sing. I love to dance. I won rock ‘n’ roll competitions when I was young! Those friends I danced and sang with, who I did literacy drives with every summer from January 1 to March 10 — going to every isolated, muddy corner of Chile, without trains or buses. Where the peasants, the campesinos, were at the end of the world, and we taught them to read. I can describe it for you as if it happened today, the tears of a campesino, when he could put words together and write his name. I was 15 years old, and I saw that man — not one, but 10, 15, whom I taught to read — crying, with those leathery faces, those hands, that emotion. To see a man crying, hard, because he learned to read! And next to me [were] young people like myself, teaching people how to read during our entire vacations. We would teach “La Cartilla del Campesino” [The Campesino’s Booklet] because, at that time, campesinos had no salaries. They received a cookie, a piece of bread, and two truckloads of used clothes per year.

EF: You were motivated by the death of your compañeros?

MG: Yes, because I have no immediate family, really. My father died when I was 13. My family were those friends with whom I taught literacy classes, studied. They bought me shoes and fed me. They were marvelous friends, and they never, ever used guns. They never thought that death was the way in which injustice would change in Chile. And I don’t know why, but I’ve always felt that they are with me. I confess — I must be honest — it’s been hard. Sometimes I’ve said to myself, “How much longer!? No, no, I don’t want this anymore. Why should I continue? I want to live.”

Once I went to the cemetery in 1990 to visit the tomb of someone very important, someone who in a way represented my friends, and I told him, “I did my duty. Now leave me or stay with me, but in a good way. I don’t want to keep feeling guilt for being alive.” Because that’s what happened at the end, I am alive, and they are dead, and why? It’s unfair. Many among them were much better than me, much more honest, much more authentic.

And I’ve always felt that I have a debt. I owe them something, and the truth is that after going to the cemetery, I felt free for a while, but they are still with me. They accompany me in a good way. That is, I no longer feel I owe them something, although I feel that if they were here with me today, in Chile, where I have children and grandchildren, they’d say “Mónica, we are traveling down a good road. There are many things to do, but we crossed the abyss.”

EF: What kind of threats did you get when you were first reporting criticisms of Pinochet?

MG: Many, but I confess that the first thing that happened — something I’ve only recently learned — is that I had surprised them. Some of those people I’ve denounced — and I’ve talked to many whose names I’ve printed — said that it was surprising to them that someone would dare to say something like that in an article written under her real name.

Now, about the threats. What were they? They’d kill your dog, and they’d kill it in the most brutal manner. I came home one night, I opened the gate, and there was my dog, still warm. They cut him up with a machete in his stomach five minutes ago, as if saying, “This could have been you.” He was my pet, my companion….

Phone calls. Many times they arrested me. They entered my house and searched it many times.

Once, they placed a bomb in my car. I never had a car until I had a partner. Three months after we got together, his car exploded five minutes after we got out of it. House searches, cars parked in front of the house, and in them were guys with submachine guns who’d shoot inside. What did that feel like? That I could not plan for tomorrow, that I couldn’t think of tomorrow, because I didn’t know if I was going to be alive.

I live for today, and I fight fear anyway I can. I look for support and here comes the second factor: I was not alone. The information that I receive, the help that I receive is from a people, from a Chile that was overcoming its fears.

I was not a superwoman. I was very afraid, but there were so many people who supported me, who gave me little gifts, who treated me so well, who wrote to me, who loved me, who were defeating their own fears in their work and at home. Because there’s no such a thing as a superwoman or superman. I was part of an enormous, anonymous group of Chileans who were making history.

EF: I know that many people were great, but many people also simply hid and did nothing while you withstood terrible things in prison. Tell me about that.

MG: I discovered that the “death machine” wants to eliminate the strongest people. I have the privilege of being strong. I had sent my daughters into exile. It was just me at that point. There were no close relatives to endanger. So the only thing they could do was to kill my soul as a woman, and they tried to do that. They humiliated me. They raped me. They almost succeeded, but no, I was lucky, because I understood that [destroying my soul] was the way to eliminate me.

You always have to understand death machines. The key element is to understand its logic, and its logic is to destroy the weak at their weakest point: their character. They wanted to make a victim of me, and the victim would be a victim forever. And I said, “No.” They didn’t destroy me. I was not totally alone. I had friends, people who helped me see that there’s a horizon — something to look towards. There are two options: either you say that in your life you will accept violence and injustice because life is just like that or you decide it is NOT like that. There is always a little space of light or humanity.

I am privileged. I have learned from other people that you can find humanity in the darkest places. Even as you are being raped, there is a man who says with his eyes, “What a horrible thing I am doing.”

***

The following interview took place on December 15, 2006, five days after Augusto Pinochet died of a heart attack in the Military Hospital of Santiago. Judge Juan Guzmán had, in December 2004, ruled that Pinochet was medically fit to stand trial and indicted him and placed him under house arrest. By 2006, other Chilean judges had also indicted Pinochet. At the time of his death, he faced more than 300 criminal charges.

***

MG: The first thing I thought of on Sunday when I learned that General Pinochet had died, and it was confirmed that he was going to be cremated, was that it was unbelievable.

He won’t have a tomb!

He condemned thousands of Chileans to be disappeared, to be thrown in the desert or in abandoned mines, so nobody would ever find them or remember them. And he — not because of the force of the bayonet, but because of the fear of his own people — will be another disappeared person. I’m convinced that for many people, it’s still very difficult to believe.

In 1974, after the coup, Pinochet had built a great tomb, a mausoleum, in the cemetery at his mother’s request. But his mother died many years later, in 1986. And when his mother died, they buried her there, and soon afterwards, the grave was desecrated. Pinochet realized then that he could never be buried there. The times had changed. So he changed his dream to a grand Napoleon-style tomb inside the Military Academy. But the army didn’t accept that. And that’s interesting: today’s army didn’t accept him having a tomb inside the Military Academy.

The family had to accept that they must cremate him because his body would never be safe anywhere. As we have seen, more than one child or grandchild, more than one survivor of his crimes, someone who was tortured and survived was going to open that tomb so that nobody would ever find a milligram of his remains. But what I like is that nobody condemned him to suffer that. His own family did it out of fear. It’s incredible how history has changed.

Thirty-three years ago, those who were scared down to their bones were those who opposed him, and he was the Almighty who declared, from some hidden spot in the headquarters of the coup d’état, “Se mata la perra, se acaba la leva.” Today, his people are the ones who are afraid of what is to come. That’s why they had to burn him, incinerate him at more than 1000 degrees Celsius, incinerate him with the coffin in which he was placed. Not a trace of that coffin will be left.

When I saw the ashes [when Pinochet was being cremated], that long cloud of black ashes going up, it was as if in Chile we were delaying the return of the monster. We signaled that murderers get punished. If someone wants to obtain glory by killing, torturing, imprisoning, throwing bodies into the ocean with their stomachs split open, they won’t get glory. What they’ll receive is reproach.

EF: I was surprised by the vehemence of both the hate and the love towards Pinochet, even though those people shouting his praises in the streets knew what he had done. How do you explain that?

MG: It’s true, there was love, there was vehemence, because I think what happened on the day he died was an explosion in which the masks came off. Countries have very few opportunities to experience those moments.

The pinochetistas, who have for many years hidden their love for Pinochet and their hate towards all those who think differently, are unable to control it. Their real personality comes out from deep inside them.

EF: What’s in the soul of a human being in society that allows these things to happen?

MG: It’s happened since the Roman circus, and probably before that, when an emperor gave a thumbs-down sign and an entire people screamed for blood, and those Christians or slaves died in the most brutal way in front of the crowd. That story repeats itself time and again. Today, it’s worse because there’s anesthesia. We see via a TV screen where journalists look for blood to show the audience, and the more blood, the greater success. Those 60,000 fervent, hot-headed pinochetistas, had so much hatred in their eyes and gestures. If you’d given each of them a machine gun, I don’t know what they would have done or how many people they would have murdered.

There’s a death machine, which is there, latent. I think this country is like a clock, which marks a pulse each minute, tick-tock, tick-tock, it’s the pulse of the country, the sound of the streets. The streets talk: they speak of the rage, the sadness, the passion, the pain of the citizens.

We have to look into their eyes and decipher those words full of hatred because when you don’t listen to them, they reach more people. They conquer more spaces. Their hatred invades everything. It’s very dangerous. We have to stop it.

That’s the task of journalism, to alert us when there’s hatred, to alert us when hate expands through the streets, to alert us when madmen acquire positions of power, to alert us when there’s someone who isn’t democratic [who is] in control of weapons in a certain army unit, to alert us to not allow permissive judges to be judges, to not allow antidemocratic generals to remain in the army.

It’s a clock that we must treat with great care because if we don’t, what has happened before and has always happened will occur again. But we shouldn’t lose hope. Our work consists of this: how to delay the return of the monster.

Sunday evening something very powerful happened to me, a whirlpool of images as I drove towards Santiago after learning of Pinochet’s death. I had to keep moving, working, writing articles for Clarín newspaper that afternoon. I had a whirlpool of images — it was very powerful — images I thought were no longer registered in my memory, but they were very clear images, even odors, of many tough episodes. And suddenly, at one point during the evening, I got a terrible chill because I realized — and to this day I am terrified to say this — that I have two children because of Pinochet, because I could have had more, but I lost them. I have the loves I have had, the lost loves, and those I had, the pain I’ve gone through, the hours without love, the discipline, the crankiness, the desire to cry that I sometimes feel, the happiness I feel — so many things of mine have depended on what that madman has done. Fue muy fuerte… It was very strong….

Elizabeth Farnsworth is a filmmaker, foreign correspondent, and former chief correspondent of the PBS NewsHour. Her 2008 documentary, “The Judge and the General,” co-produced and directed with Patricio Lanfranco, aired on television around the world and won the DuPont Columbia Award, among other honors.

María José Calderón is a Chilean documentary producer and editor based in Oakland, California. She associate produced “The Judge and the General” and has produced and edited documentaries for PBS, Latino Public Broadcasting, Univision, and other networks.

Mónica González Mujica is a Chilean writer and journalist, winner of the UNESCO/Guillermo Cano World Press Freedom Prize. The interviews were conducted in 2004 and 2006 during shoots for “The Judge and the General,” which first aired on POV(PBS) in 2008.

1. In 1974, DINA established itself as the principal arm of repression of the Pinochet regime and received technical, training, and infrastructure support from the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency. In the summer of 1975, DINA chief Manuel Contreras was put temporarily on the CIA payroll.

2. The film can be viewed on YouTube in English [ https://youtu.be/2v7yTGnb970 ], French [ https://youtu.be/WM1wA3sPch0 ] and Spanish [ https://youtu.be/EgCJlbrLYWM ].

3. In other words, “If we kill Allende, we get rid of his followers.”

4. Bishop Sergio Valech was a fierce defender of human rights in Chile. He assumed control of the Vicaría de la Solidaridad (Vicariate of Solidarity) during the last years of the dictatorship (1986-1992). The Vicaría was created in 1976 by the Catholic Church and other religious institutions to defend and promote human rights in Chile. For decades, the Vicaría collected testimonies of victims and relatives of those imprisoned, tortured, and disappeared during the military regime. In 2013, Bishop Valech directed the National Commission on Political Imprisonment and Torture, which created the Valech Report, a record of human right violations during Augusto Pinochet’s military regime.

5. Judge Juan Guzmán used the term “permanent kidnapping” to refer to those crimes that last as long as they are being perpetrated. In a kidnapping, the crime lasts from the moment a person is illegally deprived of freedom until they are released or until that person appears, even if dead. The 1987 Amnesty Law had shielded Pinochet and all involved in criminal acts as authors, accomplices, or accessories, committed between September 11, 1973, and March 10, 1978, without making a distinction between common crimes and those committed with political motivation. In a “permanent kidnapping,” the crime of kidnapping and disappearance continued to be committed continuously, so the amnesty law could not be applied since it referred to crimes committed within a specific period.

6. Enrique Arancibia Clavel was the head of the clandestine network of DINA in Argentina. He was arrested in Argentina in 1978 and charged with espionage. After the arrest, his apartment was raided and more than 500 confidential DINA documents were found, seized, and filed in the Federal Court of Buenos Aires. Those are the documents referred to by Mónica González in the interview.

7. The “DINA documents” include cables, intelligence reports, and correspondence between Arancibia Clavel and his bosses in Santiago between 1974 and 1978. They reveal torture and disappearance techniques used by the Argentine death squads, as well as their cooperation with the Chilean intelligence agency to kidnap, torture, and disappear Chilean refugees in Argentina in operations known as Colombo and Condor, among others.

8. David Silberman was a member of the Communist Party and the General Manager of the Cobre Chuqui copper mine until the military coup of 1973. On October 4 of the same year, he was detained by DINA agents and taken to a clandestine detention center from which he disappeared. In 1975, a mutilated body was found in Buenos Aires, Argentina, with an identity card that identified him as David Silberman. Later that body was found not to be Silberman, who continues to be among the missing.

9. No relation to Mónica González.

10. Pinochet’s dictatorship ended in 1989 when he conceded to holding elections and lost to Patricio Aylwin. Shortly thereafter, President Aylwin established Chile’s National Commission for Truth and Reconciliation — known as the Rettig Commission — to investigate human rights abuses that occurred during the Pinochet regime.

11. Mónica’s father, Luis Antonio González, was an anarchist railway worker. He studied law but didn’t finish. He died after being hit by a train. “He showed me, without hatred, the French Revolution, wars, and many other historical and contingent issues so that I would understand in which world I was standing” (http://www.bibliotecanacionaldigital.gob.cl/colecciones/BND/00/RC/RC0057...).

12. At age 14, Mónica González started participating and volunteering in different activities organized by the Chilean Communist Party through the Federación de Estudiantes Secundarios de Santiago (FESES, Federation of Secondary Students in Santiago), like the winter and literacy campaigns in rural areas. In 1965, when she was 16, she formally joined the Youth Communist League and later the Communist Party of which she was a member until 1984.