Urban poverty reduction, particularly efforts to improve the livelihoods of slum dwellers, is one of the greatest challenges facing global policymakers. The United Nations Human Settlement Programme estimates that by 2030, an additional 2 billion individuals will live in the Global South, and the vast majority will reside in urban slum communities. Rio de Janeiro exemplifies this trend: it is both one of the world’s most luxurious cities and the site of hundreds of poor urban neighborhoods, known as favelas.

Janice Perlman has been working in favela communities since 1968. Her early research resulted in the seminal work The Myth of Marginality, which argued that, contrary to conventional wisdom, favelas were not marginal in any sense. Instead, these communities were tightly integrated socially, politically and economically with the rest of the city. Therefore, the problem for favela residents was not that they were disconnected from Rio, it was that their ties with the wider city were characterized by exploitation and repression. In this way, the “myths” of marginality were not only false, they were particularly damaging with respect to the way they justified inequality and legitimized favela eradication policies.

The intervening decades brought renewed attention to the issue of urban poverty. Population growth in urban areas exploded around the world, and Rio de Janeiro was no exception. Mirroring global trends, the city’s poor neighborhoods grew more rapidly than Rio as a whole in the period from 1950 to 2000. Government officials responded with a variety of policy strategies, ranging from eradication efforts to infrastructure improvement projects within targeted favelas.

However, none of these strategies was successful in checking favela growth, either in terms of population or geographic area, and their impact on alleviating poverty was minimal. Why did public policy fail to transform Rio’s favelas, and how have these communities changed over the intervening years? In 1998, Perlman returned to Rio to find out. The results of her multi-generational study were published in Perlman’s recent book, FAVELA: Four Decades of Living on the Edge in Rio de Janeiro.

However, none of these strategies was successful in checking favela growth, either in terms of population or geographic area, and their impact on alleviating poverty was minimal. Why did public policy fail to transform Rio’s favelas, and how have these communities changed over the intervening years? In 1998, Perlman returned to Rio to find out. The results of her multi-generational study were published in Perlman’s recent book, FAVELA: Four Decades of Living on the Edge in Rio de Janeiro.

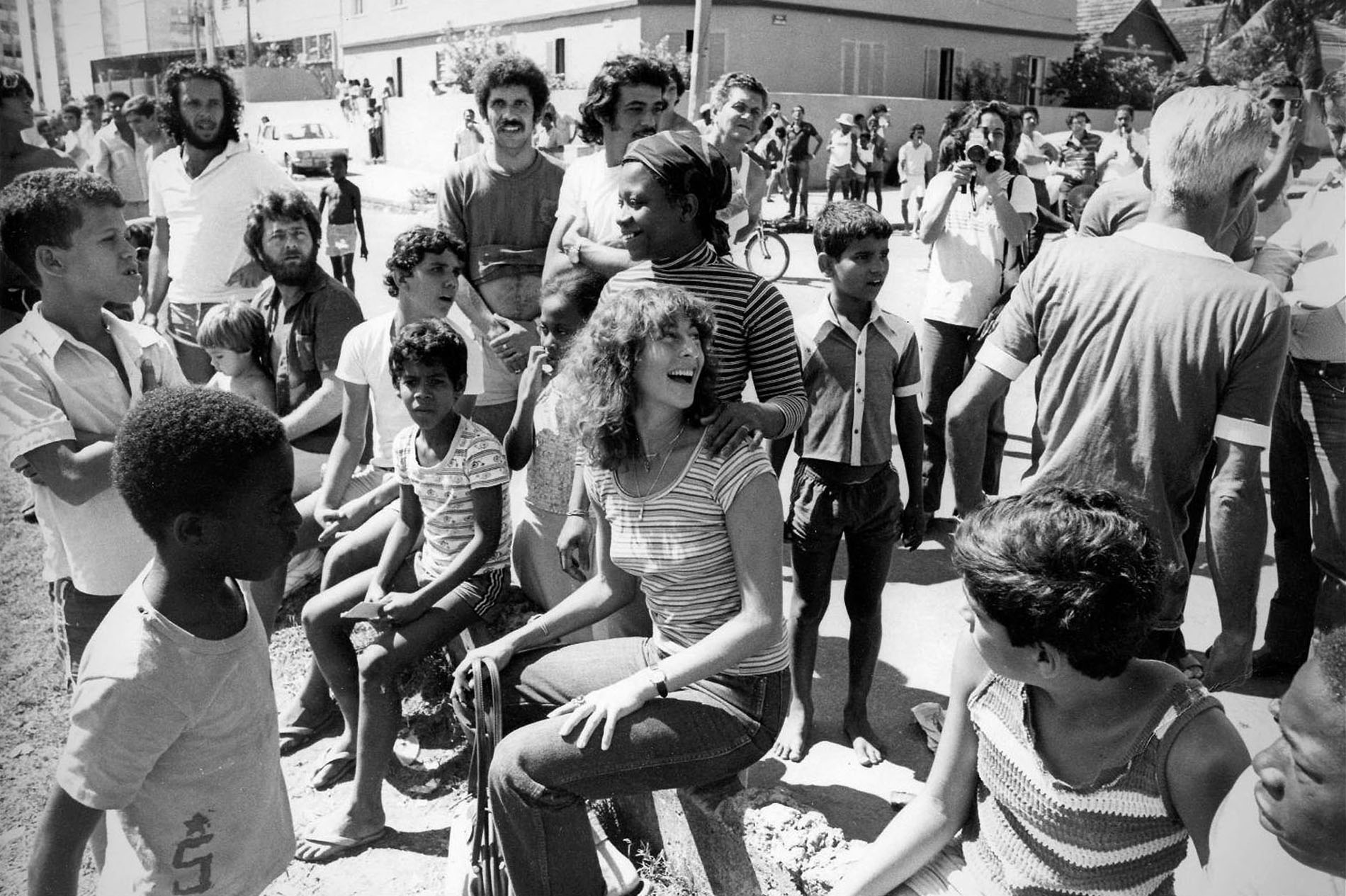

Perlman explained that the first challenge in conducting longitudinal research was finding the original study participants. Due to fears of repression during the dictatorship, interviewees’ last names had not been recorded, and street addresses were uncommon in many communities. Moreover, one community — Catacumba — had been completely eradicated to make way for upscale condominiums on prime lakefront real estate. Nevertheless, using innovative strategies — such as driving around various communities and announcing over a loudspeaker that everyone was invited to a Saturday barbecue in exchange for assistance in locating former interviewees — Perlman managed to reconnect with 41 percent of those who participated in the original study.

Over the next 10 years, Perlman collected quantitative and qualitative data from the original participants and a sample of their children and grandchildren as well as from a random sample of residents who did not participate in the original study in order to control for bias. Her rigorous methodology resulted in rich, detailed insights regarding the dynamics of urban poverty over time. Pairing statistical data with favela residents’ personal stories, Perlman vividly conveyed the changes that transpired, both in the lives of individuals and in their communities as a whole.

Has life gotten better for favela residents over time or has it become worse? Perlman contends that the answer to both questions is yes. On the positive side, living conditions have improved in many communities. In 1969, few houses had indoor plumbing, electricity or running water, but decades later, most residents have access to these amenities at home. Public areas such as plazas and soccer fields have been upgraded, and some main streets have been paved. Even satellite dishes are occasionally present today. Interestingly, Perlman noted that these infrastructural improvements were made regardless of whether or not the community was part of a formal favela renovation project. Living conditions in communities that were never selected for an upgrading project were equivalent to those that were. Perlman explained that, in many cases, residents improved their own communities without assistance from government programs.

Favela residents also have access to many domestic goods at levels that are comparable to Rio overall. Telephones, TVs and refrigerators are commonly found in homes, and more people than ever before own washing machines, air conditioners and a fixed telephone line. Car and computer ownership remain much higher in the formal areas of Rio than in the favelas, but these rates are on the rise in favelas as well, especially among the grandchildren of the original study participants.

Educational levels have also increased dramatically. In 1969, 72 percent of the original interviewees were illiterate; by 2001, the illiteracy rate for these same individuals had dropped by almost half, to 45 percent. More strikingly, only 6 percent of their children were illiterate, and among the grandchildren, the illiteracy rate was 0 percent. Moreover, at present 61 percent of the grandchildren earn their living through non-manual jobs, and 11 percent have attended university.

If one looks only at living conditions, access to domestic goods and educational attainment, it would be easy to conclude that life for favela residents has improved substantially. But, Perlman emphasized, despite these material and educational improvements, favela residents feel more marginalized than ever before. This perception may be due in part to the expansion of the drug- and weapons-trafficking gangs that solidified control over most favela communities during the mid-1980s. However, Perlman claims that the roots of modern marginality go much deeper.

For example, impressive educational gains do not translate into higher incomes for favela residents. Perlman cited Brazilian economist Valerie Pero, who found that a favela resident needs to complete 12 years of schooling to equal whan a non-favela resident earns after only six years of education. In addition, jobs requiring unskilled, manual labor are increasingly scarce. Perlman related a striking anecdote: in years past, parents used to encourage their children to study so that they wouldn’t have to work as garbage collectors. However, almost 40 years later, when a few vacancies opened up in the city sanitation department, thousands of people turned out to apply — and all of the available positions required a high-school diploma.

Moreover, some jobs are simply unavailable to those who live in favelas. Discrimination is unapologetically rampant. Perlman noted that, for favela residents, the following story is all too common: the interview might go extremely well, but as soon as one’s address is revealed to be in a favela, the interview is over, and the position is mysteriously no longer available. Perlman’s quantitative data reinforced this finding. Being “from a favela” was the most frequently mentioned basis for discrimination, outpacing skin color, appearance and gender. In light of this reality, it is unsurprising that despite their higher educational levels, 50 percent of all the grandchildren in Perlman’s study remain unemployed.

The lack of access to formal employment is just one way that Brazil’s return to democracy in the mid-1980s did not deliver on its promises for favela residents. Even though citizens have the right to vote, to join parties and unions and to participate in political life, many are quite cynical when it comes to politics.

Personal security, access to health care and stable employment are further out of reach for favela residents than ever before. Faith in elected officials has been correspondingly eroded. Only 38 percent of Perlman’s interviewees thought that “government tries to solve our problems” — a sharp decline from the 61 percent of individuals who responded similarly to this question during the dictatorship years. Youth in particular are keenly aware of corruption, including the control that the trafficking gangs exercise over their communities, and therefore, Perlman states, they tend to withdraw from political participation entirely.

The most pernicious aspect of the new marginality, however, is the way in which residents of favelas have been increasingly dehumanized. Forty years ago, marginality may have been a myth but, according to Perlman, today it is all too real, especially in terms of citizenship and personhood. Favela residents are closely tied to the life of the formal city of Rio, but they are not considered true citizens. Instead they are “an invisible part of the infrastructure that makes life workable for the privileged elite.” In order for the upper classes to maintain their lifestyles, as well as their peace of mind when facing stark inequalities, it is necessary for there to be not only a flexible lowerclass workforce but also a prevailing sentiment that these individuals deserve their fate.

Reasons for this state of affairs are varied and reach back as far as the beginnings of Rio de Janeiro itself, when the city was segregated along race and class lines. Today, violence in the favelas is a reality, but it also presents an excuse for residents of the “formal” city to perpetuate the idea that favela residents do not deserve the same rights as everyone else. In turn, when one is constantly passed over — for jobs, for medical care and even for attention in public shops and banks — it engenders a lack of self-esteem that fuels a pernicious downward spiral.

Therefore, for favela residents, respect and dignity do not come hand-in-hand with educational or professional success. Perlman described in vivid detail the way respondents would talk about striving to become gente — to become “somebody,” a human being — and their despair as they realized that, despite a life of hard work and education, attaining the status of “fellow human being” in the eyes of others may be permanently out of reach.

Perlman concluded her talk with a few thoughts on the public policy implications of her findings. Most policies aimed at improving poor communities and alleviating poverty tend to focus on infrastructure — upgrading roads, sanitation, buildings and the like. However, the overwhelming priority for the favela residents that Perlman interviewed was access to good jobs. Improving urban services is undoubtedly beneficial, but it is steady work and a rising income that allow a favela resident to become gente, a person with dignity.

For example, Perlman suggested, what if Rio’s city government decided to hire only favela residents to perform the work necessary to prepare for the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympics? Providing well-paying jobs for residents would do far more to improve these communities than building elevators and paving roads.

In addition, there is a strong commitment among favela residents to democratic participation in theory, if not in practice. Perlman found that in 2001, 61 percent of the original interviewees believed that “every Brazilian should participate in politics,” almost double their response from decades ago. In order to translate these ideals into reality, it is necessary to raise the self-esteem of favela residents, particularly young people. If the younger generation can recognize their self-worth and see themselves as gente, citizens deserving of the same rights and responsibilities as anyone else, they may begin to challenge public perceptions of favela residents.

Historical, cultural and structural forces have certainly shaped life’s realities for residents of Rio’s favela communities. City government leaders and policymakers must rise to the challenge of successfully integrating these neighborhoods into the city on an equal footing with non-favela areas. Moreover, as favela residents themselves refuse to be complicit in their own marginalization, they may demand public policies that address issues that truly matter and that reflect the dignity and worth all human beings deserve, regardless of where they live.

Janice Perlman is a researcher, consultant and nonprofit leader who founded the Mega-Cities project (http://www.megacitiesproject.org/) and recently published FAVELA: Four Decades of Living on the Edge in Rio de Janeiro. She spoke for CLAS on February 23, 2011.

Wendy Muse Sinek is a Ph.D. candidate in the Charles & Louise Travers Department of Political Science at UC Berkeley.